Opinion Focus

- Brazil is highly dependable on ethanol for fuel security, with ethanol responsible for over 40% of fuel supply in Brazil.

- Government decisions on gasoline prices could lead to a long term risk of fuel shortage.

- Decision to end the tax exemption can result in a potential upside for ethanol prices – even with a gasoline price reduction.

Light vehicles in Brazil can only run on gasoline (with a 27% ethanol blend) and/or hydrous ethanol. Diesel use has been forbidden since the 70s, as a result of the oil crisis. Being a country of continental proportions, and one highly dependable on moving goods by roads, the government at the time needed to guarantee the fuel supply for trucks.

Brazil hasn’t changed much, we still use roads as the main way to transport products from one place to other – close to 65% versus 15% for railways.

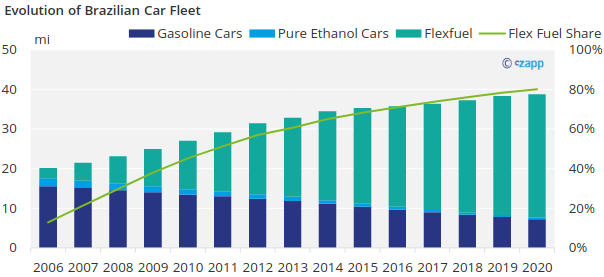

As a result, the Brazilian car fleet evolved mainly for gasoline and ethanol vehicles. With the introduction of the flex fuel (FFV) technology in 2003, the car fleet now is composed of over 80% of FFV.

Source: Anfavea, Czapp

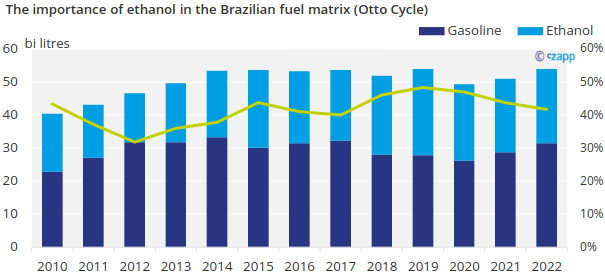

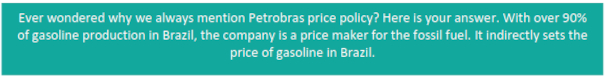

When looking at fuel consumption in Brazil, we therefore focus on what is called what is called “Otto Cycle” (combustion engine fuel demand).

Brazilian Otto cycle fuel consumption reached 54bi litres in 2022, the second highest on record. And out of this total, 42% was ethanol – including anhydrous for gasoline blend and hydrous for FFV.

Source: ANP, Czapp

Brazil is highly dependable on ethanol for fuel security, which is why changes in tax policies and Petrobras price policies can create uncertainty for the future role of ethanol and long-term supply.

Fuel Shortage, Not an Option

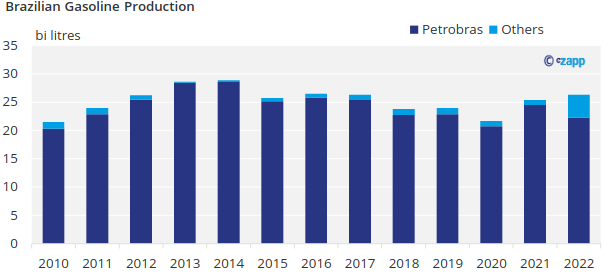

Brazil has a limited capacity for refining oil into gasoline, estimated at around 30bi litres. So, the gap for fuel demand in Brazil (at around 25bi litres) needs to be filled by ethanol and gasoline imports. Brazil ethanol output capacity, in years when the market incentives producers to maximize sugar and minimise ethanol, is around 30 bi litres already including corn ethanol – more on that below.

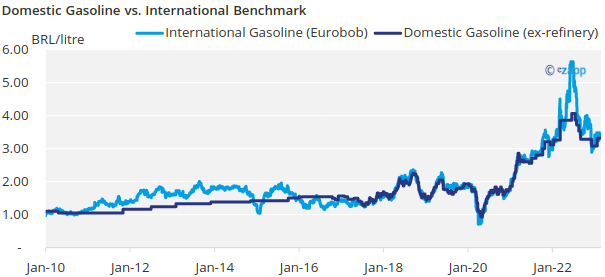

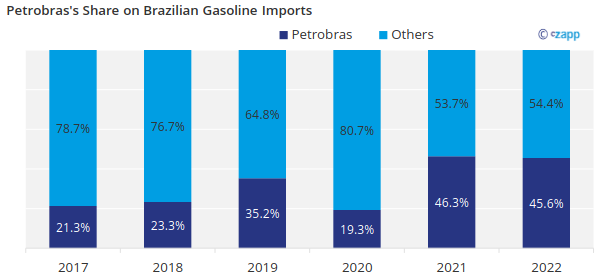

Until 2019 Petrobras was responsible for over 95% of total gasoline production in Brazil. Then, in 2019 a deal was made with Cade (Administrative Council for Economic Defence) that Petrobras would need to sell 50% of its refining capacity in order to end the company’s monopoly. That would result in selling 8 of its refineries. So far it has succeeded in selling 2.

Source: ANP, Czapp

With the change in Government after the 2022 presidential elections, the mindset for selling these remaining refineries is now the opposite. Rumours are that the government will try to make a deal with Cade to go back on the commitment set in 2019.

The result? Either Petrobras will need to increase refinery capacity (a new refinery would take at least 4 years to be built), gasoline imports will need to rise and/or maybe ethanol’s role in in fuelling the country will need to be reflected in the price. Something that with tax exemptions and discussions of shifting away from the current International Price Policy (IPP) is hard to bet the latter as the winner of the options.

Assuming an average 4% growth in fuel demand, by 2025 gasoline imports would need to be at least 3bi litres. Not the maximum Brazil has ever imported, but the figure assumes ethanol production rising on the back of corn ethanol projects already expected to be implemented in the next couple of years -according to UNEM (Union of the National Corn Ethanol Producers) in 2025 production should grown 30% to 6bi litres.

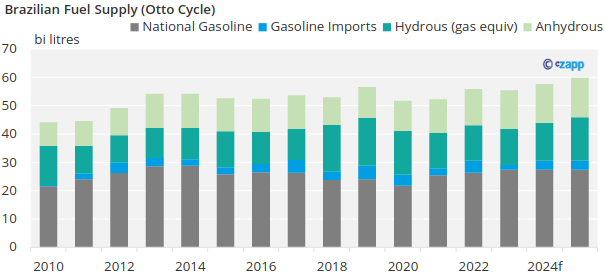

Another key assumption is that consumer will keep favouring ethanol. However, like we saw with the changes in tax policy, a persistent gasoline ethanol parity above 70% impacts consumer preferences, resulting in lower hydrous ethanol share – lower ethanol preference, more gasoline needed.

Source: ANP, Czapp

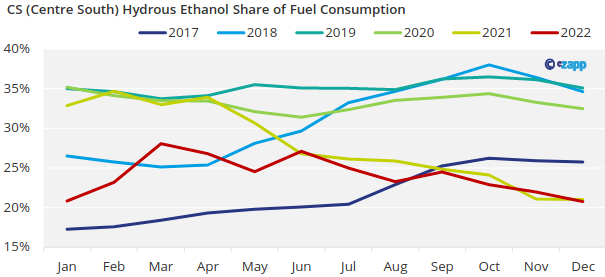

If Petrobras does forgo the IPP, then the company will once again find itself importing at a loss like it did between 2012 and 2015. This created an estimated loss of over BRL40 bi for the company. Hard to invest in refinery when there is this gap to fill.

Like we said, fuel shortage is not an option. The only player willing to import at a loss will be a company owned 50% by the government. Other players will excuse themselves from the obligation.

Source: ANP

When the IPP was implemented in 2017, we already saw an increase of different players participating in importing gasoline. But in 2021 and 2022, when the price adjustment became less frequent and domestic prices were below international for a longer period Petrobras participation once again rose.

Gasoline Prices Capped are Negative for Ethanol

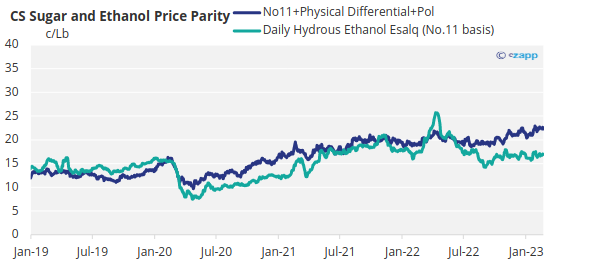

Consumers will choose between gasoline and ethanol based on the price ratio rule dubbed as the gasoline ethanol price parity. If below 70%, consumers will buy ethanol over gasoline.

What this implies is that in order to maintain a favourable ratio, every time gasoline prices come down (either by lower taxes or lower refinery prices), ethanol will also need to reduce to remain competitive.

In a scenario where domestic prices do not follow the international benchmark, as being proposed by the new government, any upside in Brent will not be reflected domestically and consequentially ethanol prices will remain capped.

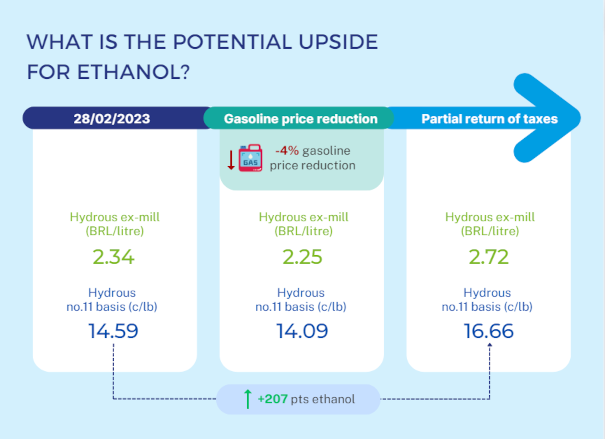

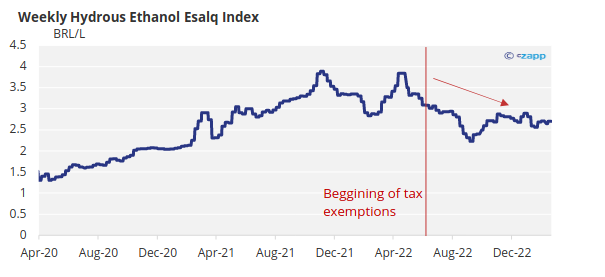

The government has decided to end the federal tax exemption for gasoline and ethanol. And at the same time, it seems forced a decision from Petrobras to reduce gasoline prices by 4%.

The announcement made last night left much doubt on what exactly will be the new taxes, the Finance Minister seemed to forget about Cide and said that the return will be “0,47/litre for gasoline but with the gasoline price reduction is actually BRL0,34/litre”. Is that the final impact? The only clear note was the positive externality for ethanol was maintained – i.e, ethanol tax difference is sustained as per the Constitutional Amendment 123 of 2022.

What is the impact for ethanol? From the timeline above we can see is positive. The gasoline price reduction alone would create a downside of 50 points for ethanol. The return of taxes, even if not at 100% and the lower tax burden for ethanol, results in a 200points upside for ethanol – given the lack of clarity in the announcement we are considering the full return of Cide tax on gasoline at BRL0.1/litre.

Source: Esalq

In Summary

By creating artificial mechanisms to keep gasoline prices down, the government pushes away private investment in refinery capacity creating a potential long term supply risk. How long could Petrobras incur losses on imports?

Additionally, the critical role of ethanol in keeping the country fuelled is in dire need of recognition. By subsidizing gasoline, the ethanol price potential is reduced. Additional production capacity is pushed ever away – especially with sugar paying producers 38% more than ethanol.