Opinion Focus

- Soaring energy costs hit dairy industry hard.

- Labour shortage means dairy workers can leverage higher pay.

- Packaging prices have more than doubled

Lurpak — a popular brand of butter in the UK — has hit the headlines recently due to soaring prices, which have reached as high as GBP 9.35 (USD 11.17) for a 1-kilogram portion. Arla, the dairy firm that owns the brand, recently responded by saying that the price rise was in response to higher input costs and that it wanted to ensure it was paying farmers a fair price. So, are farmers being paid enough to produce butter?

It’s a Slippery Slope

UK supermarkets have faced outrage from consumers after a favourite butter product hit the headlines. Lurpak butter is now on shelves at up to USD 11 for 1 kilogram, up about 30%, and shoppers are not happy.

While the issue may seem trivial with plenty of other butter and spread options on offer, this story offers a snapshot into today’s environment of rising food prices. But perhaps more importantly, it gives insight into the tight margins and operational pressure farmers are facing today in trying to feed the planet.

Dairy firm Arla – the producer of Lurpak – pays its farmers a fixed rate for the milk they provide. The company operates as a cooperative and, in addition to monthly payments, farmers receive a share of Arla’s annual profits, calculated based on the amount of milk supplied by the farm.

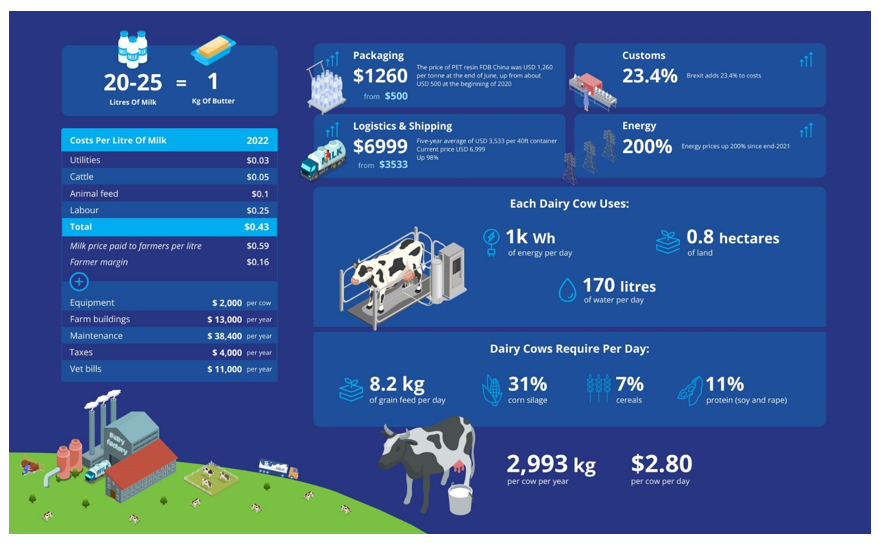

On June 27, Arla issued a press release to say it would increase its farmer payments by EUR 0.02 a kilogramme for conventional milk and EUR 0.01 a kilo for organic. This would bring the farmgate milk price to around USD 0.59/litre for conventional and USD 0.66/litre for organic milk.

This is quite a substantial jump from Arla’s July 2019 prices. Three years ago, the company was paying its farmers about USD 0.36/litre for conventional and USD 0.50/litre for organic milk. This marks a 64% increase in conventional milk costs and a rise of 32% in organic milk costs.

Given that Lurpak’s final unit costs have gone up by about 30%, it is clear that the culprit is the rising cost of dairy. So why are prices on farms rising so sharply?

Input Prices Rise

For farmers, there are a lot of prices to contend with. Firstly, they need cattle to produce the milk required for butter. According to USDA data, the actual cost for a dairy cow is around USD 1,500 per head on average.

The average milk yield per cow is about 10,000 litres per year. But dairy cows can only usually produce at these levels for about three years. This would mean each USD 1,500 cow produces 30,000 litres of milk in its lifetime, giving us a milk price of USD 0.05 per litre.

But this is far from the full story. The price of the cow itself is a drop in the ocean, with farmers having to integrate feed, energy, equipment, land, animal care and labour costs too.

Feed Cost Stabilises, Remains High

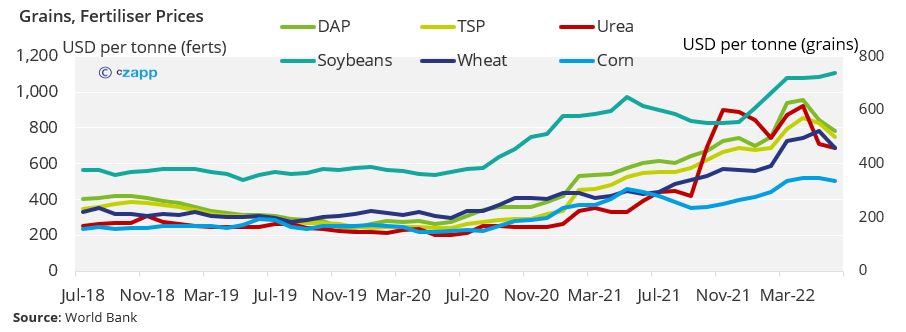

The cost of animal feed has risen steadily in recent months due to the increasing cost of grains. This is due to a variety of factors, including high fertiliser prices, caused by high energy prices, which have been exacerbated by the war in Ukraine.

A dairy cow requires a varied diet consisting of forage, grain, mineral supplements and protein-rich feeds such as soybean meal.

Dairy cows require a great deal of grains. According to a research paper, about 31% of the diet is corn silage, 7% cereals and 11% protein consisting of soy and rape. Given that a dairy cow consumes about 8.2 kilograms of grain feed per day, that’s about 2,993 kilograms of grain a year per cow.

At today’s prices, this would come in at USD 2.80 a cow per day. Over the lifetime of the cattle, feed alone would cost USD 3,066.

There is now a new worry for Danish dairy farmers. About half of a dairy cow’s daily feed intake comes from forage. But now, Europe’s heatwave is heading north and meteorologists are warning of the possibility of a drought. This would apply more pressure on farmer bottom lines as it means more feed would need to be brought in as feed dries up in the hot sun.

Farms Feeling Utility Pinch

Energy requirements of dairy farms can vary greatly but in general they are very energy intensive. In one study in Ireland, on average 31.73 megajoules or 9 kilowatts of energy was required to produce 1 single litre of milk. To put that into context, that is equivalent to running the dishwasher for 4.5 consecutive hours or using an air conditioner for three hours.

The largest energy use resulted from milk cooling. Other factors to consider are lighting inside barns, as well as energy used during the milk pasteurisation and ripening stages.

Energy prices vary across Europe but at the end of 2021, the average rate for Europe’s non-household customers was about EUR 0.14 a kilowatt-hour; but energy prices in 2022 have already trebled., taking those tariffs up to about EUR 0.42/kWh.

So, assuming each dairy cow uses about 1kWh of energy per day, a farm of 200 dairy cows would be facing an energy bill of about USD 30,660 a year.

Water too does not come cheap. According to Farmers Weekly, water requirements can be as high as 170 litres per cow per day on a dairy farm. So that 200-cow dairy farm? It should expect to pay about USD 31,700 per year in water.

Further Input Costs Pile Up

As well as buying the cow itself, the farmer needs to ensure it withstands three lactation cycles. This of course involves animal health costs including vet bills and housing. As a rule of thumb, up to two acres of land (0.8 hectares) is required for each dairy cow.

According to the NYS Dairy Farm Business Summary, the equipment investment per cow is approximately USD 2,000. There is also an average investment of USD 12,296 a year in farm buildings. Maintenance costs a further USD 38,392 per farm. Taxes are about USD 4,000 per year on average. But of course, these costs vary wildly from country to country and are harder to quantify.

In the case of Lurpak, quality control is another intangible. Arla says it requires dairies to submit samples to a panel of independent experts every week. There is also an exhaustive list of potential bovine diseases that animals can become susceptible to. To maintain yields, dairy cows must be vaccinated and remain in good health, which requires regular veterinary check-ups. According to Statistics Denmark, each Danish farm spends about USD 11,000 a year on vets’ bills.

One of the biggest expenses in most agricultural operations is labour costs. The average dairy farm with a herd of 100 cows requires 12 staff members. If every staff member works 50-hour weeks at the minimum wage of USD 16, that equates to an annual payroll of almost USD 500,000.

There is even higher risk of rising prices given the shortage of labour. Workers are likely to command higher salaries to combat the rising cost of living, which eats into the farmer’s bottom line.

More Costs Further Downstream

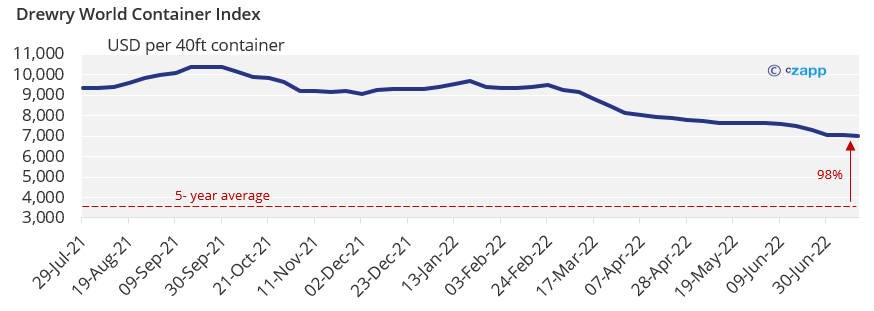

All these costs relate only to milk procurement. After Arla purchases it, the milk has to be processed, packaged and distributed. For the processing stage, Arla already has factories across Europe, but these all require operating costs such as energy and l bour.

Lurpak comes in various packages, including foil, cardboard boxes and plastic tubs. The cost of packaging materials has risen exponentially since the e-commerce boom during lockdown. At the end of June, the price of PET resin FOB China was USD 1,260 per tonne, up from about USD 500 at the beginning of 2020.

For UK consumers, there’s another consideration. Brexit has increased export burdens for Arla shipping its product to the UK. Leaving the customs union has had an impact on declaration costs, port check times, product of animal origin (POAO) checks and potentially organic certification, rules of origin (ROO), tariffs and quotas. An analysis from LSE Consulting estimates that these checks add up to an extra 23.4% to shipping costs.

It is worth mentioning that Lurpak is subject to legal origin protections, much like Champagne, Scotch beef or Darjeeling tea, so it can only be produced in Arla’s Danish facilities. This means these extra cost burdens cannot be avoided.

Concluding Thoughts

After the backlash over the price of its butter, Arla released a statement defending the costs, saying the price rose to help its farmers cope with ever tighter margins.

“Unfortunately, our farmers are facing a similar situation with prices for the feed, fertiliser and fuel they need to produce milk, all rising significantly in recent months,” it said. “While we don’t set the prices on the shelves, we do work closely with the retailers to ensure our farmers receive a fair price for the milk they produce.”

Arla is paying farmers USD 0.59 per litre for milk, and about 20 litres of milk are required to make 1 kilo of butter. It is therefore not hard to see how the rice could stack up to over USD 10.

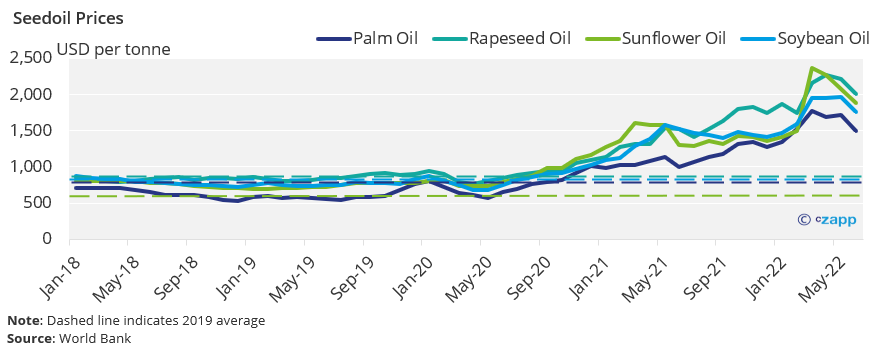

While consumers do have options and there are alternatives to Lurpak butter, the price pressure on farmers remains due to rising input costs. Even those switching to alternative oil spreads will feel the pinch due to the surge in oil seed prices caused by the war in Ukraine.

Energy prices are climbing ever higher but the good news is that some of the other costs, such as fertilisers and feed, may be starting to stabilise. However, Arla’s chief commercial officer Peter Giortz-Carlson has warned that milk farmers are making a loss on their products due to rising input costs. He told Sky News that this is set to worsen as farmers struggle to cover costs.

Other Insights that may be of interest

What the Energy Crisis Means for Inflation & Commodities

Have the Indicators the Supply Chain Should Monitor Changed?

Interactive Data Reports that may be of interest …

Consecana Panel

CS Brazil Weather Update