Insight Focus

- The war in Ukraine has reshaped global shipping corridors and trade patterns.

- A series of logistics challenges and sanctions have complicated matters.

- We take a look at how European and global freight has changed in the past two years.

On February 24, 2022, the invasion of Ukraine by Russia marked a significant escalation of the eight-year conflict between the countries and a historic turning point for European security. For international shipping, this has meant disruptions to global trade and increasingly limited trading capabilities with Russia as stronger sanctions come into play, especially those imposed by the European Union (EU).

Two years on, we take a look at how European and global freight has changed in the past two years.

Early Invasion Creates Lockdown

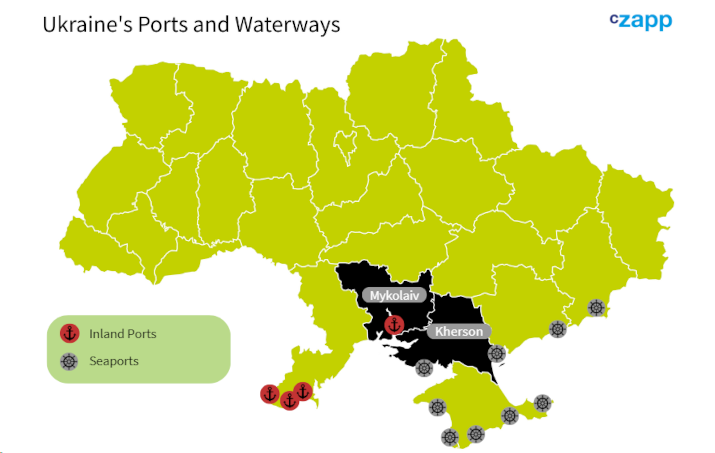

In the first three months of the war, Ukrainian logistics faced the biggest disruption since WWII due to the blockade of Black Sea ports by Russian Navy forces. The Ports of Mariupol and Berdyansk on the Azov Sea were also blocked due to the ongoing warfare, while shipping traffic came to a halt. Dozens of international vessels were unable to leave Ukrainian ports.

Inland waterways were also affected. Ports on the Dnipro River, which extends from the north of Ukraine to the Black Sea in the south, also suspended their operations due to the maritime blockade and the following Russian offensive on the Kherson and Mykolaiv regions.

According to Informall Business Group, a cargo analytical and consulting company in Ukraine, the three Danube River ports of Izmail, Reni and Ust-Dunaisk gradually picked up the pace. They began to handle all kinds of cargo a few weeks after the invasion.

The first shipments occurred in April-May 2022, primarily consisting of grains and vegetable oil. During the same period, the country’s port and hinterland storage infrastructure was reviving and developing. It is important to note that these shipments have increased steadily since then.

Source: Informall Business Group

Additionally, there was heavy congestion in overland logistics and at cross-border points, particularly in the first few weeks of the invasion, with a significant influx of vehicles heading towards EU countries.

“By three months into the conflict, congestion mainly involved trucks and rail wagons, with a decrease in civilian transport volumes,” noted Daniil Melnychenko, Analytics Consultant of Informall BG.

Danube Ports Pivot

In the 12-month period between June 2022 and June 2023, Ukrainian Danube River ports, such as Izmail, Reni and Ust-Dunaisk, began handling various types of cargo, focusing mainly on agricultural products.

Initially, there was a shortage of barges, and congestion at channels, namely at Romania’s Sulina and Ukraine’s Bistre, according to Informall. While Ukrainian Danube River ports were designed to handle mainly bulk and general types of cargo, ocean containers still found their way via the port of Reni and later Izmail, adapting the available port equipment.

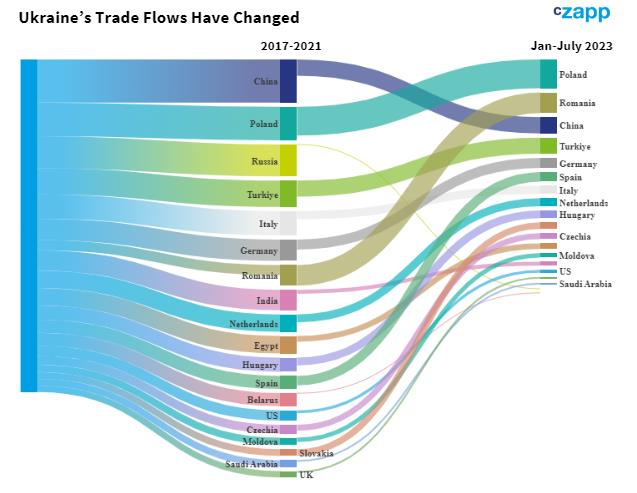

Other important ports in Europe, such as Poland’s ports in Gdinya and Gdansk, Romania’s port of Constanta, Bulgaria’s port of Varna, Lithuania’s port of Klaipeda, Germany’s port of Hamburg and Italy’s port of Trieste started to gain traffic, with exports shifting to these hubs via rail and road.

As Ukrainian deep-sea ports remained inaccessible and air strikes persisted on Danube River ports, Ukrainian exporters began to shift their focus towards neighbouring nations like Poland, Romania and Bulgaria, as well as extending their reach to Baltic countries such as Lithuania and Latvia.

Much of the exported cargo was directed towards these countries for transit, intending to be transhipped through their deep-sea ports to Egypt, Indonesia, China, Bangladesh, Turkey and to Northern Africa and Middle Eastern countries. Those are historically the main markets for Ukrainian grains and vegetable oil.

Source: Informall Business Group

Consequently, the substantial influx of Ukrainian grain has triggered market disruptions at the local level in Poland and Romania, prompting farmer protests and blockades at border crossing points at the end of 2023 and into early 2024.

Black Sea Trade Tentatively Resumes

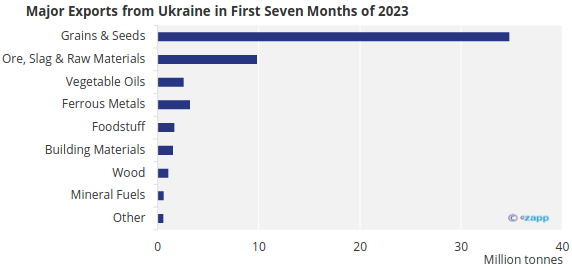

Despite the ongoing conflict, Ukraine’s export portfolio has remained largely unchanged. Grain, agricultural products, foodstuffs, and metals continue to serve as the cornerstone of the country’s economy.

However, significant challenges have arisen due to the accumulation of large grain volumes prior to the invasion, with up to 25 million tonnes now trapped within the country. This surplus has left farmers with extremely limited storage space as they prepare for the upcoming crop season.

Source: Informall Business Group

In response to the storage crisis facing Ukrainian farmers, the United Nations intervened by brokering a deal with Russia. This agreement led to the establishment of the Joint Coordination Centre (JCC) in July 2022, in Istanbul, Turkey.

The purpose of the JCC was to implement the Black Sea Grain Initiative, which aimed to create a humanitarian maritime corridor. This corridor allowed ships to transport exclusively grain and vegetable oil from three crucial Ukrainian ports in the Black Sea: Odesa, Chornomorsk and Pivdennyi (Yuzhny).

This initiative allowed for a continued (although greatly reduced) flow of grain exports from Ukraine through Black Sea, according to Dryad Global, a UK-based maritime risk intelligence technology company.

Corridor Continues Despite Russian Withdrawal

In July 2023, Russia formally withdrew from the United Nations-brokered deal, thus significantly raising the risks of sending grains via the Black Sea. Noah Trowbridge, Analyst at Dryad Global, added that “these risks extend to neighbouring Romanian waters where vessels seek to call at Ukrainian ports, while vessels are recommended to cooperate and fully comply with naval authorities.”

Since Russia’s withdrawal from the Black Sea Grain Deal, Ukraine set up a maritime humanitarian corridor guarded by Ukrainian military forces along the Romanian and Bulgarian coasts. Slowly, Ukrainian Black Sea ports began to regain volumes, leading to the shift from the Danube inland waterways back to conventional deep-sea shipping.

Source: UN Comtrade, Ukraine Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food

In addition to grains, Ukraine has expanded its export portfolio to include commodities such as iron ore and metals, while also increasing imports, particularly of fertilizers.

As of today, the Black Sea Humanitarian Corridor has facilitated the safe passage of 515 ships, transporting a total of 16.5 million tonnes of grain and cargo to global markets. Remarkably, the export rate of agricultural products has nearly returned to pre-war levels, accompanied by a substantial decrease in cargo insurance costs.

Ukraine Regains Black Sea Channel

This achievement is attributed to Ukraine regaining control over the western part of the Black Sea. The absence of the Russian navy in this region is ensured by Ukrainian sea drones and the deterrent of missile threats. Although air raids on Ukrainian ports persist, they are less frequent and effectively repelled by air defence forces.

Russia subsequently increased its airstrikes on storage and civilian infrastructure in these ports to limit Ukraine’s ability to export its grain through the Danube and Romanian ports. However, “through these combined trade channels, Ukraine has been able to sustain unexpectedly high levels of exports,” said Trowbridge.

This corridor facilitates reliable export and import of goods, although container shipping remains challenging, according to Informall analysts, who say that ocean containers are primarily shipped via Poland and Romania. Reni and Izmail both serve as a destination for export and import containers, as they benefit from direct shipping lines.

Future Developments

According to Dryad Global, the higher logistical and time constraints associated with Ukraine’s alternative exports channels via the Danube and land routes means that Kyiv is eager to develop its Black Sea corridor. This is demonstrated by its ability to negotiate discounted war risk premiums for vessels transiting this route in November 2023.

Analyst Trowbridge pointed out that Ukraine’s ability to strike at key Russian naval assets off Crimea has further bolstered its posture in the region and added that, despite the stabilisation of frontlines in the conflict, a rapid and unexpected escalation of military activity in the maritime domain cannot be excluded in the months to come.

Ukrainian wheat is typically harvested between July and August and incidentally, Russia launched regular airstrikes on Ukraine’s Danube ports over this period in the last year.

“Considering the volatility of the Black Sea security landscape, Ukraine will have to rely on its more costly alternative trade routes to sustain its economically critical grain exports,” concluded Trowbridge.