Insight Focus

- This year’s COP climate summit will kick off in Dubai on November 30.

- Funding for cutting carbon emissions will be a major point of discussion.

- Meanwhile, more technical work will go into shaping the new UN carbon market.

World Set to Miss 2.5 Degree Target

Negotiators and experts from more than 195 countries are meeting this week in Dubai for the 28th annual Conference of Parties (COP) to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. At the conference, world leaders will discuss how to boost efforts to wean the world off fossil fuels in time to meet the agreed goal of net zero emissions by 2050.

Carbon markets will be part of the agenda in Dubai, but after several years of high-level political discussion, work on emissions trading is likely to be comparatively technical and low-key.

COP28 will host the first Global Stocktake, a five-yearly review of countries’ climate pledges – or Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) – intended to ensure that countries are steadily ratcheting up their decarbonisation plans.

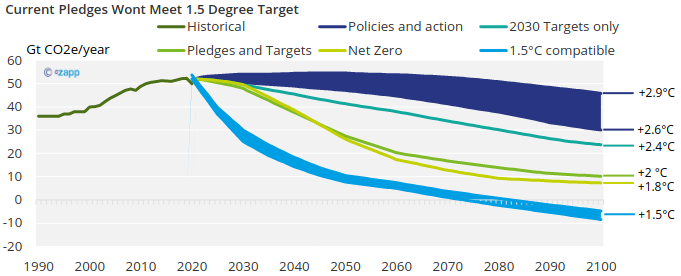

The early signals aren’t positive though. Analysis of current NDCs shows that the world is still on track to see global average temperatures rise by 2.5 degrees Celsius by 2050. So, we should expect a steady drumbeat of calls for greater ambition.

Source: Climate Action Tracker

Money a Major Bone of Contention

There will also be disagreements – lots of them – about money.

At the COP meeting in 2009 the developed world set itself a target of providing USD 100 billion a year in finance to the developing world by 2020 to help with cutting emissions, as well as adapting to the effects of climate change.

Experts are confident that this USD 100 billion target was reached this year, just in time for a discussion over a “new collective quantified goal”. Two years ago, there was consensus that the figure should be doubled by 2025, but with other, newer commitments having been agreed, this target may also slip.

The most high-profile of these new commitments is a global Loss and Damage Fund, agreed at last year’s COP in Egypt.

The Fund was set up to deliver support to victims of climate change around the world, such as Pacific Island nations whose homes are being washed away by rising sea levels.

But technical discussions this year over where the Fund should be housed, who should be eligible for support and who should control the spending spiralled into disagreements, and only an eleventh-hour deal saved the work.

Developing countries are particularly unhappy that the Loss and Damage Fund will now be housed at the World Bank, in which the US has the largest shareholding. “We know the history. We know the politics. We know the manipulation,” one developing country delegate was reported as saying at the final meeting.

UN Carbon Market Takes Shape

Carbon markets will play a relatively minor role in Dubai. That’s because the main political agreements have all been reached, and experts are now working on fleshing out the political decisions into a rulebook that will guide investors, project developers and countries.

The main body tasked with setting the rules, the Article 6.4 Supervisory Body, completed its work for 2023 this month and will send two important documents to the COP for approval.

The first sets out the criteria that will determine how projects calculate the emissions reductions that they turn into carbon credits. These calculations will need to be conservative and to decline over time.

Projects will need to generate emission reductions that go beyond a host country’s already-established climate policies and ensure that new technology is transferred to developing countries.

A second set of guidelines sets down principles that will govern projects that actively remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere, projects such as carbon capture and storage, direct air capture or planting new forests.

A critical part of this guidance involves setting aside a portion of the removal credits in a “buffer pool”. In the event of a reversal – a forest fire or a venting of stored CO2 – these buffer credits would be cancelled to offset the effect of the reversal.

If COP28 signs off these guidance documents, the Supervisory Body can begin work on detailed procedures and criteria for projects to earn UN approval, which may lead to the first projects being formally approved as early as late 2024 or early 2025, and the UN’s new carbon market will be underway.