Insight Focus

Nations are set to discuss raising “trillions” to fund the net zero transition at COP29. US participation is uncertain following Donald Trump’s election. Carbon market talks will be tense after the panel’s unilateral move.

Climate Finance Takes Centre Stage in Baku

Nations are gathering in Baku for this year’s annual UN climate summit, the Conference of the Parties (COP), where the agenda is dominated by climate finance and increasingly ambitious targets.

But looming over it all will be the shadow of an incoming US president who has threatened to quit the climate treaty. Donald Trump has already pulled the US out of the Paris Agreement once, complaining that it didn’t require enough effort from developing countries. Some observers have suggested he may now go further by withdrawing from the overarching UN climate convention.

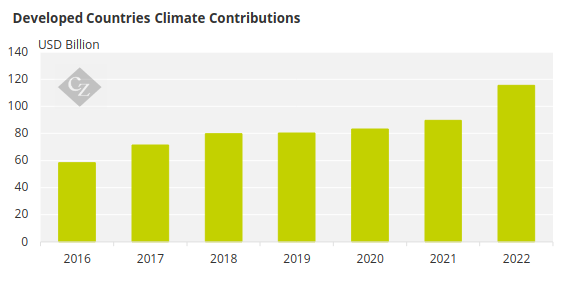

Top of the agenda is finance. In 2009, world leaders agreed to mobilise funding worth USD 100 billion a year by 2020 to assist developing countries in addressing climate change. It took a couple of years longer than planned, but the USD 100 billion mark was eventually reached, and now countries are set to discuss the “new collective quantified goal” for climate finance.

Source: OECD

Given how much has changed since 2009, and how much more the world understands about the cost of the energy transition and the race to net zero, the numbers this time are considerably higher. Some experts have said the developed world needs to channel trillions, not billions, of dollars annually to emerging and developing economies that don’t have the means to fund these efforts themselves.

And with Donald Trump’s election to the White House last week, securing the necessary funds is likely to become even more challenging. The US has long resisted calls for it to increase its contributions to the global climate fight. Congress, which holds the purse strings, has always insisted that it will contribute as long as its other major trading partners (a not-so-subtle reference to China) do the same.

However, China, Brazil and other emerging economies are firmly maintaining their status as “developing” countries under the UNFCCC. They continue to emphasise that wealthier nations like the US and Europe must take the lead, insisting the West should set an example. The debate in Baku is expected to be intense.

Nations Set to Update Climate Pledges

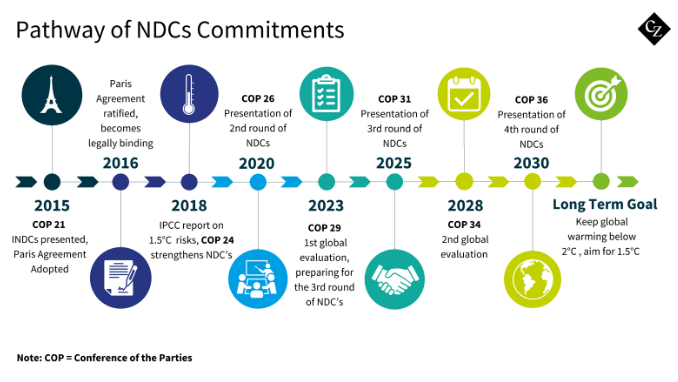

Nations are also expected to start submitting new and updated Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs, or UN-speak for national climate pledges) at the talks. These targets represent commitments to cut greenhouse gas emissions in the period ending 2035 to stay on track to limit global temperature increases to less than 2°C by 2050.

Already, though, most NDCs that have been announced are judged by climate experts to be insufficiently ambitious. In fact, the World Resources Institute said, “The actions outlined in existing NDCs are on track for a catastrophic 2.5-2.9°C of warming by 2100.”

The deadline for the next round of NDCs is in February, but observers expect a steady flow of updated commitments in Baku.

Carbon Markets on Agenda in Baku

The final high-profile agenda item in the Azeri capital will be carbon markets. At the Dubai summit last year, negotiations over key building blocks of the new global market broke down acrimoniously, with some nations insisting on greater UN oversight, while others countered that national governments should take precedence.

There were also important disagreements on guidelines for carbon-cutting projects, which are designed to earn tradable carbon credits that can be sold both to governments and private-sector buyers.

Last month, the UN-appointed panel that operates this “Article 6.4 mechanism” took the unusual step of formally implementing new project guidelines, without waiting for the UN summit to approve them.

This move places the onus on the COP to simply approve the Article 6.4 Supervisory Body’s (SB) decision or to push back and insist on proper procedure.

Baku will likely see some countries complain about what some are calling the SB’s overreach. But others point out that the UN negotiations have failed for three years to agree on basic ground rules for projects. They say the SB’s actions reflect frustration with the political process and serve as a clear reminder that time is running short.

And while the UN works through its daunting agenda, market participants on the sidelines of the COP will meet to discuss the progress of the voluntary carbon market (VCM).

Over the last year, the VCM has been buffeted by negative media coverage and occasional scandals, and current carbon credit prices reflect reluctance by corporate buyers to link themselves with questionable credits.

Progress in Carbon Standards

However, there are signs of progress. The International Civil Aviation Organisation, which regulates a mandatory global carbon credit market for airlines, called CORSIA, has recently approved four new additional standards organisations to register CORSIA-compliant credits.

The new eligible standards include Verra, the world’s largest carbon credit standard, and stakeholders are optimistic that the approval will lead to a steep increase in the volume of credits available to airlines in the coming year.

While the carbon market discussions in Baku are unlikely to directly affect the European and UK compliance markets, they offer valuable insights into the long-term evolution of carbon crediting, particularly in the development of plans to incorporate carbon removals into the EU and UK ETS frameworks.