Insight Focus

Consumers appear to continue to be willing to pay for convenience. This is true even despite rising inflation and general economic uncertainty. One way for soft drink manufacturers to absorb potential agricultural tariff costs—if supplier concessions were unfeasible—is to optimise production mix. The high-level evidence points to potential pricing power in canned soda. Let’s take a look at the evidence.

Soft Drink Growth Continues

The US soft drinks industry continues to project significant growth over the second half of this decade. However, this growth may not be equally beneficial to all form factors.

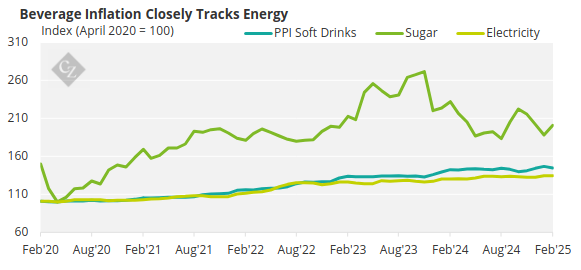

First, the cost of soft drink production has risen by over 44% since the pandemic. However, this growth does not appear to be significantly driven by the cost of sugar, as consumers are increasingly seeking low-sugar or sugar-free alternatives to the traditional carbonated beverages.

Instead, production costs of soft drinks track much closer to the cost of electricity, which has risen by 34% during the same period.

Source: St Louis Fed

Consumers appear to continue to be willing to pay for convenience. This is true even despite rising inflation and general economic uncertainty. One way for soft drink manufacturers to absorb potential agricultural tariff costs—if supplier concessions were unfeasible—is to optimise production mix. The high-level evidence points to potential pricing power in canned soda. Let’s take a look at the evidence.

Source: St Louis Fed

The Production Cost Factor

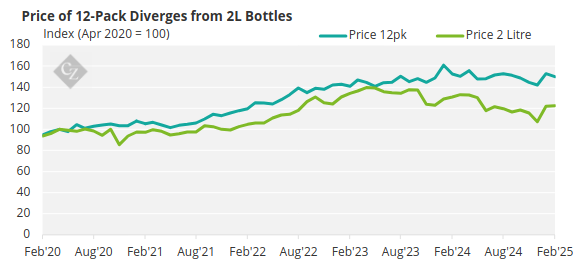

The question, then, is whether this was driven primarily by the cost differential in their production? After all, regardless of the form factor, the actual input ingredients of the soft drinks for any single product are the same.

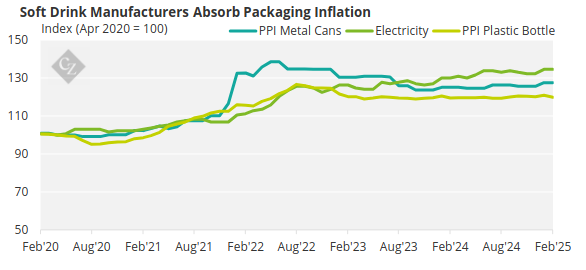

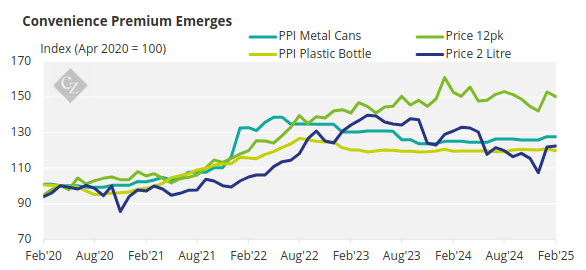

In other words, what’s inside a can of Coke should be highly similar to what’s inside a two-litre bottle, with perhaps only a very slight difference in the overall degree of carbonation. As it turns out, the cost of making metal cans and plastic bottles did not fully explain the divergence in retail prices for the two different soft drink packaging.

If anything, it appears that the price of canned 12-packs did not experience the significant cost shock to aluminium that took place at the beginning of 2022. Instead, soft drink manufacturers likely absorbed much of the cost without passing them on to consumers.

Source: St Louis Fed

So, what does explain the divergence? Looking at all of the above cost factors and price indices together, a picture begins to emerge.

Source: St Louis Fed

Fundamentally, different customer segments buy two litres and 12-packs. Whereas two-litre buyers are cost-conscious and economy-minded, 12-pack buyers are more driven by convenience. Moreover, two-litre bottles must be consumed quickly after opening. In contrast, a 12-pack of soda can be consumed in 12 different separate occasions.

The combination of added convenience and post-opening stability likely allow soft drink manufacturers to command higher prices relative to two litres.

The Broader Implications

There is a significant limitation to this strategy, however, due to the looming tariff on aluminium imports. In addition, the global price of aluminium remains highly sensitive to production. For instance, the early-2022 aluminium price shock was due to China placing a cap on aluminium production as well as energy costs.

The added cost will require soft drink manufacturers to further reconsider how to package drinks. As the fundamental driver of 12-pack sodas is “convenience,” can packaging innovations result in plastic bottles being used in place of aluminium cans?

Beyond manufacturing concerns, there are other aspects to consider as a part of distribution optimization. For instance, plastic can weigh less than aluminium for the same capacity. However, what is the implication on a bottler’s palletization of the soft drink or unit load stacking for shipping?

After all, savings harnessed through packaging changes can be easily compromised if products get damaged en route to stores.