Opinion Focus

- Grains exports from Ukraine are continuing despite a Black Sea blockade but at a much-reduced rate.

- Ukraine’s allies are seeking alternatives to Black Sea ports, including switching to road and rail freight.

- The drop in grain availability could spell disaster for countries in the Middle East and North Africa.

Ukraine is one of the world’s biggest wheat exporters, but the Russian invasion means its infrastructure is crippled and seaports are unable to load grains from storage silos into bulk containers for Black Sea shipments. With an inability to reach seaports, other options to avoid a global food crisis would be shipping grains by rail, but this would present issues with infrastructure, routes and volume constraints.

Russian Blockade Cuts of Critical Grains Port

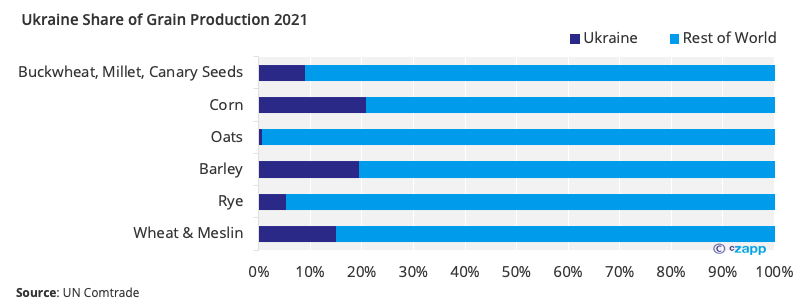

The war in Ukraine has not only sparked a humanitarian crisis within the country, but its agricultural strength means the consequences reach much further than its borders. Ukraine is a major grains producer, accounting for a major share of the world’s grain production.

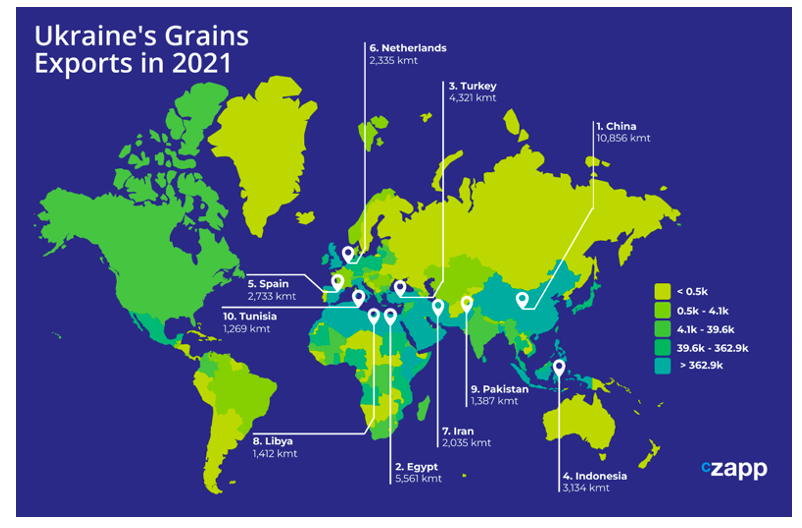

Ukrainian grains are also largely exported to developing countries, particularly in the Middle East and North Africa. Egypt is hugely dependent on Ukrainian grains, as are Libya and Yemen. Turkey exports large quantities of wheat through Black Sea bunkers trade to mill wheat flour that is then sent to these lower-income countries.

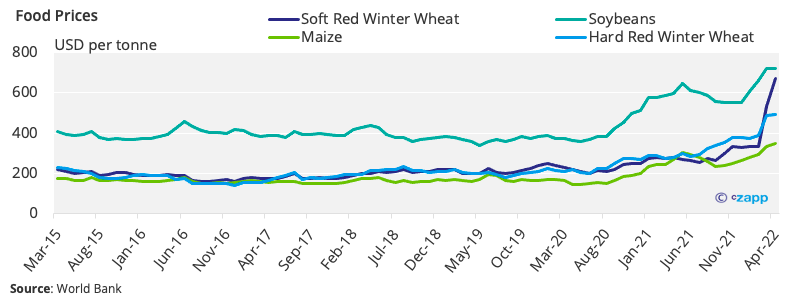

If Ukraine’s grain supply is choked off from the rest of the world, this could have grave consequences for global food security. As global food prices continue to rise, an increase in the cost of staples such as wheat could prove problematic. The last time wheat prices rose as sharply as they have over the past year was in the immediate run up to the Arab Spring protests.

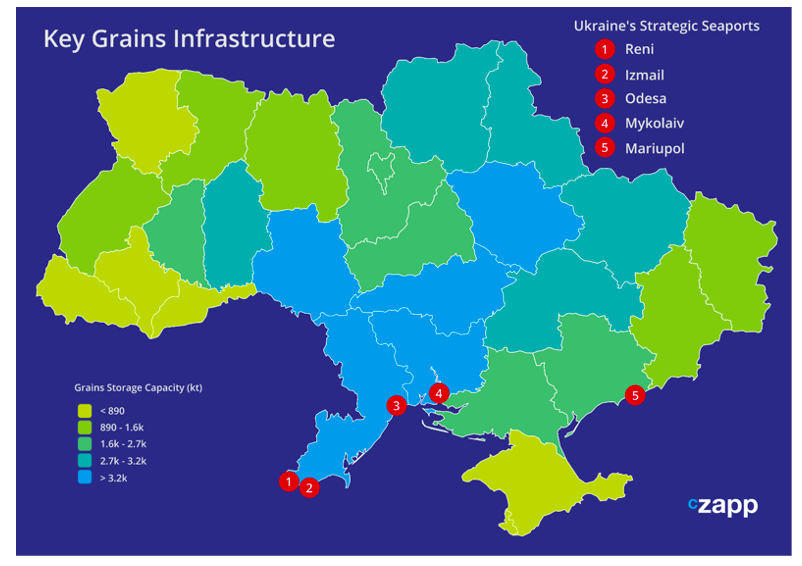

As the war in Ukraine rages, critical grains planting, harvesting and transportation has been disrupted. Grain producing regions are generally focused in the centre of the country. Production is then transported by rail to storage silos around the ports, where it is subsequently loaded into container vessels and exported via the Black Sea.

However, the Russian invasion means that key infrastructure has been left off limits. Port have been largely inaccessible since the invasion began at the end of February, leaving huge stocks of grains piled up and nowhere to store any more harvested grain.

Russian forces have surrounded the port of Odesa, imposing a blockade that cuts Ukraine off from international export channels. In the past week, Russian forces began a missile strike on the city and port.

US, EU Look at Options to Release Grains

US President Biden last week said that efforts are being made to help Ukraine export 20 million of the 40 million tonnes of grain it has in storage to help prevent a global food crisis. The EU is also looking at alternative options that would allow grains to travel across its eastern land borders rather than by sea in an effort to ensure food supplies to developing countries are not compromised.

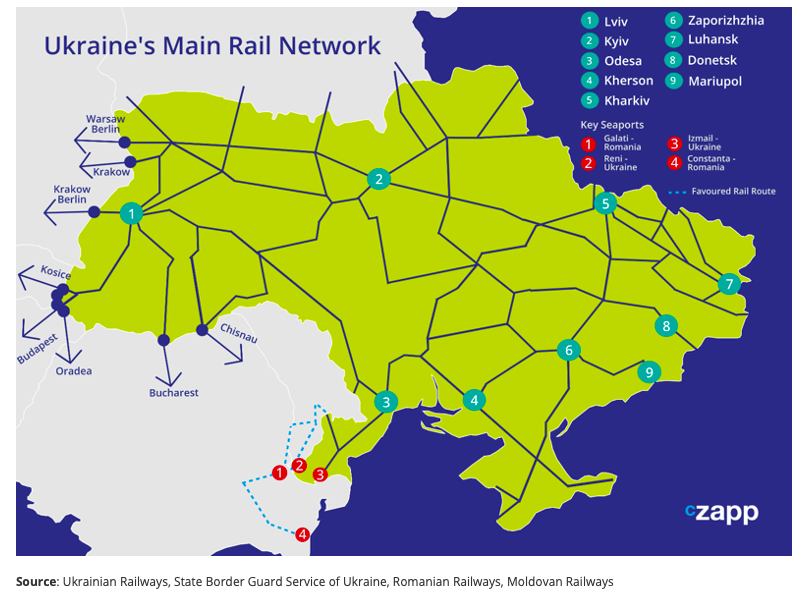

One of these options is the use of the country’s extensive rail system to transport grain into Europe through Ukraine’s land borders with neighbouring Romania, Poland, Slovakia and Hungary. The EU’s farm commissioner Janusz Wojciechowski has announced a plan to use road and rail corridors to access Poland’s Baltic ports of Gdansk and Gdynia.

The EU has also presented its “Solidarity Lanes” plan, designed to help Ukraine export its grain and avoid a world food crisis. As part of the announcement, the European Commission has called on member states to urgently make available freight rolling stock, vessels and lorries, prioritise the passage of Ukrainian agricultural export shipments through flexible customs processes and coordinate on storage efforts.

It has also signed a road transport agreement in an effort to remove bottlenecks across borders. The EC also said it will look into options for top-up financial guarantees given that sending EU vehicles into the war zone in Ukraine comes with additional risk.

Proposals have also been made for NATO forces to provide an escort system for Ukrainian and other merchant vessels to protect them. However, this avenue would run the risk of provoking a direct confrontation between NATO and Russian forces.

Romanian Exit Routes Prove Popular

Although there may be issues with grain leaving Ukraine through the Polish, Hungarian and Slovakian borders, one of the best options so far has been a route that crosses Moldova and reaches the Romanian ports of Galati and Constanta. These ports are more than capable of handling the Ukrainian grain. Constanta is the largest on the Black Sea and Galati the primary port on the Danube.

There are several benefits to this route. The rail and road links are relatively short, meaning the route is relatively efficient and costs are lower than other rail routes into mainland Europe. The cargo can then be loaded into containers or bulk vessels at the Romanian ports.

Another benefit is that Moldovan railroads use the same wide gauge 1.52m bogies as Ukrainian trains. Although Romanian trains run on standard 1.435m gauge, there is an efficient bogie changer system at the Reni-Galati border crossing. The direct crossings from Ukraine to Romania on Romania’s northern border at Vicsani, Valea Vișeului and Campulung la Tisa also include bogie conversion systems.

Earlier this month, the Romanian authorities announced a tender for the repair of an existing broad gauge train line that runs from Reni, through Moldova at Giurgiulesti and onto Galati. The tender is due to end on May 19 and the repairs must be completed 60 days after the signing of the contract. According to Ukrainian news agency Ukrinform, the ports of Galati and Constanta will be two of the key transportation points for Ukrainian raw materials and goods in the region.

This would also be the most convenient route to access the Bulgarian port of Varna. Late last month, Ukraine reached an agreement with Bulgaria to transport Ukrainian grain. No further details were given by President Vlodomyr Zelensky.

However, any route through Moldova would need to avoid its breakway region of Transdnistria where Russia has deployed what it calls peacekeeping troops. To do this successfully, Ukraine would need to avoid the Tiraspol crossing and use a rail route further south that closely hugs the Black Sea coast, leaving it vulnerable to Russian missile attacks. The EC has also stressed that this route has become saturated, and so it is necessary to look at other options – particularly through Poland, Slovenia and Hungary.

Contingency Will See Drop in Export Volumes

While the EU’s plan could be a solution to access some of Ukraine’s grain, there are several problems with these road and rail exit points. Firstly, there is a huge discrepancy between the volumes that can be transported by sea freight and land or rail freight. Even in its Solidarity Lanes communication, the EC acknowledges that the current transhipment capacity is “by far insufficient”.

Around 60 million tonnes of grain are exported from Ukraine each year. According to Ukrainian Railways, about 100,000 tonnes of grain was shipped in the first 11 days of March. This equates to about 9,000 tonnes per day. In comparison, shipping in container or bulk vessels have about 18 times greater capacity at around 165,000 tonnes per day on average.

Rail shipping should be complemented by additional lorries, according to the EC. It has proposed the implementation of a road transport agreement with Ukraine that grants granting Ukrainian and EU hauliers preferential access rights. However, even with this additional capacity, this will be much less efficient than the option of quickly reaching a seaport.

Border Delays Cause Extra Headache

There are also now reports of huge tailbacks at borders caused by technical issues. At border crossings of Chop and Uzhgorod on the Slovakian border and Izov bordering Poland, there have been tailbacks lasting up to 20 days.

This is partially caused by a discrepancy between the Ukrainian and European track gauge size. The Ukrainian railway network uses the Russian broad gauge of 1.52m, while most of Europe’s tracks are standard gauge rails at 1.435m. This means that either the train bogies need to be switched out at the border, or the cargo has to be offloaded and reloaded onto a train that can run on the tracks.

To help ease the border process, the EU urges member states to transfer available existing mobile grain loaders to the EU-Ukraine border terminals, potentially through temporary rental contracts. This would greatly accelerate the process of unloading and reloading wagons at the Polish, Slovakian and Hungarian borders.

The EC also says customs procedures at borders should be simplified to ease congestion, although warns that the measures should be “risk-based” and “proportionate”. It says border inspection capacity should be increased. However, it is not clear who would bear these additional costs.

Further Price Rises Should be Expected

Of course, a sudden increase in demand for road and rail freight has caused prices to skyrocket. According to price reporting agency Fastmarkets, Ukrainian rail transportation costs have increased by around USD 10-30 per tonne since the beginning of the war. Trucking from the center of Ukraine to the port of Reni or Izmail is double pre-war levels at around USD 65 per tonne.

And costs will only continue rising. According to Fastmarkets, shipment through Romania costs around EUR 16-25 (USD 17-26), in addition to a USD 36 per tonne premium to pass through Moldova. This then needs to be added to the cost of container or bulk freight from Galati or Constanta to the final destination.

With higher costs and smaller volumes transported, traders will have to shoulder price increases that will inevitably be passed on to the end consumer of the grains. This means the price of grains globally should continue to rise.

- There are complexities to consider with switching to road and rail freight for grains export.

- There is no simple solution to the issue – and a multi-faceted approach may work best.

- Sending grains by rail through Moldova to neighbouring Romanian seaports has so far been the most feasible alternative, but even this option carries risk.

- This could be complemented by transporting grains through the Polish border and to its Black Sea ports, but track gauge discrepancies threaten efficiency.

- Costs of grains will continue to rise as logistics burdens add up.

Other Insights that may be of interest

What the Energy Crisis Means for Inflation & Commodities

Interactive Data Reports that may be of interest …

Consecana Panel

CS Brazil Weather Update