Insight Focus

- Border tax targets carbon-intensive materials but also renewable energy and batteries.

- Sponsor says bill targets China’s “manufacturing advantage, environmental loopholes”.

- There is still uncertainty over the fee structure that would be imposed.

China-Focused Carbon Border Tax Proposed in US

Two US senators have introduced legislation that would establish a carbon border tax in the US, following the introduction of a similar measure in Europe earlier this year.

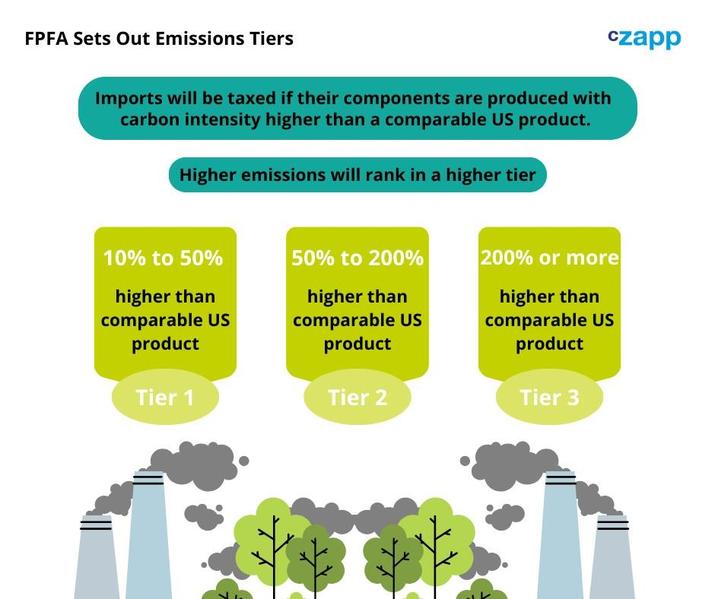

The legislation, named the Foreign Pollution Fee Act (FPFA), would set duties based on the carbon content of selected imports, with the levy applying to any listed materials with a greenhouse gas intensity of over 10% more than corresponding materials manufactured in the US.

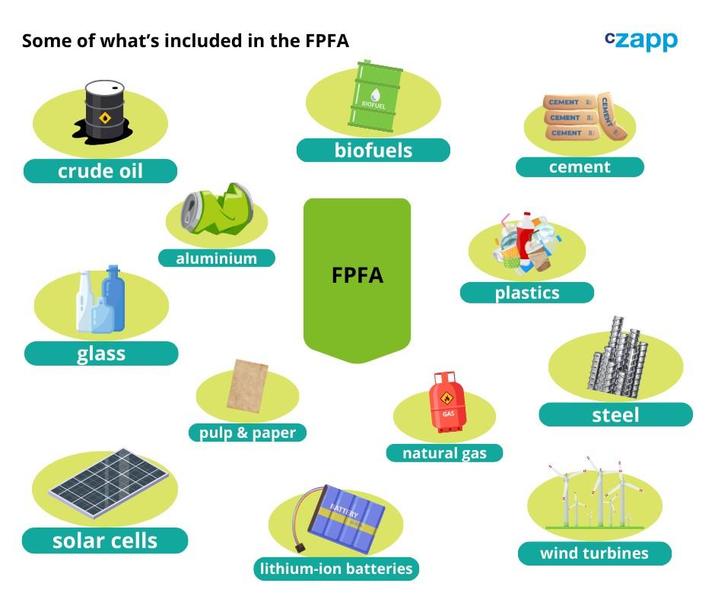

The proposed tariff would cover materials including crude oil and refined products, biofuels, cement, aluminium, glass, iron and steel, natural gas, plastics, pulp and paper.

Emissions intensity of foreign producers for the purposes of the tariff would be estimated by a National Laboratory Advisory Board on Global Pollution Challenges that would be set up if the legislation is approved.

Products that are not produced in sufficient volume in the US would be exempted from the charge, as well as products imported under free trade agreements.

The draft law was proposed by Republican Senator Bill Cassidy of Louisiana and co-sponsored by fellow Republican Lindsay Graham of North Carolina. This represents the first effort on the part of the Republican Party to address the issue. A press statement accompanying the legislation stated explicitly that the proposed carbon tariff was aimed at China. “It is unacceptable for China, or any country, to both freely pollute and export to the United States,” it said. “Allowing it to do so effectively rewards Beijing for practices Washington does not permit at home.”

Bill Runs into Some Challenges

The levy would also apply to lithium-ion batteries, solar cells and wind turbines. These inclusions have caused some stakeholders to question the true intent behind the bill, given that these products are viewed as critical to replacing fossil fuels and achieving the decarbonisation goals of the Paris Agreement.

The draft legislation also contained no information on what cost the levy would impose on carbon intensive imports. Europe’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) sets a dynamic cost per tonne based on the average weekly auction price of EU emissions allowances, but since the US does not operate a nationwide carbon pricing mechanism, it’s difficult to envisage how the levy would be set.

The FPFA does set three categories of relative carbon intensity to products produced in the US. Imports with emissions between 10% and 50% more carbon intensity than equivalent US products are in the first category, those producing between 50% and 200% more are in the second and the third applies to products that are more than 200% more carbon intensive than US products.

There is no certainty that this legislation will pass through both houses of Congress. Previous proposals along similar lines have failed to gain a foothold in committee.

Pricing Discrepancies Create Question Marks

The issue has led to wider debate about how to align carbon border taxes internationally. China already operates its own nationwide emissions trading system that today encompasses emissions totalling more than 4 billion tonnes a year. Although it currently covers just the power generation sector, there are plans to expand to other industrial sectors.

Canadian politicians have begun to discuss the country’s options, while India has suggested it could tax its exports to Europe on carbon content, thereby achieving equivalence with the European carbon price and avoiding any CBAM charges.

While many countries are beginning to set up carbon pricing systems as part of their commitment to the Paris Agreement, it’s unlikely that many of these national markets will establish a price for greenhouse gas emissions equivalent to the EU’s current price of €77.

It’s likely that CBAM will therefore require any imports of carbon-intensive materials, no matter where their source, to pay at least some charge in order to enter the EU. This means that, while the ink is barely dry on the CBAM legislation in Brussels, there’s still the possibility that Europe may need to water down the impact of its border tax.