Opinions Focus

- High energy prices threaten Europe’s oilseed processors.

- If they are rationed, can the EU import and store sufficient amounts?

- Europe needs to solve its power crisis to avoid a food crisis.

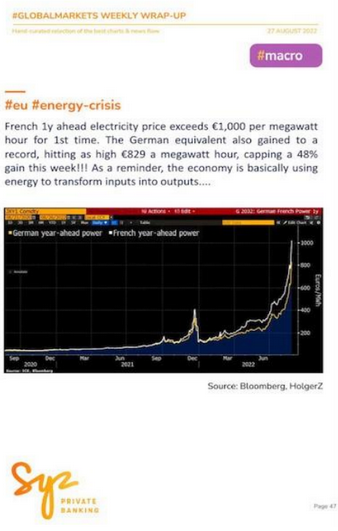

The below chart (or some version of it) has likely been seen by most of the readers of this post; this version appeared in this week’s excellent market commentary provided on LinkedIn by the Syz private bank. Given the chaos in European power markets there is a serious potential threat to European protein meal and vegetable oil production and supplies. How oilseed processing plants operate in this high-cost environment must be a great concern for the EU’s political leadership.

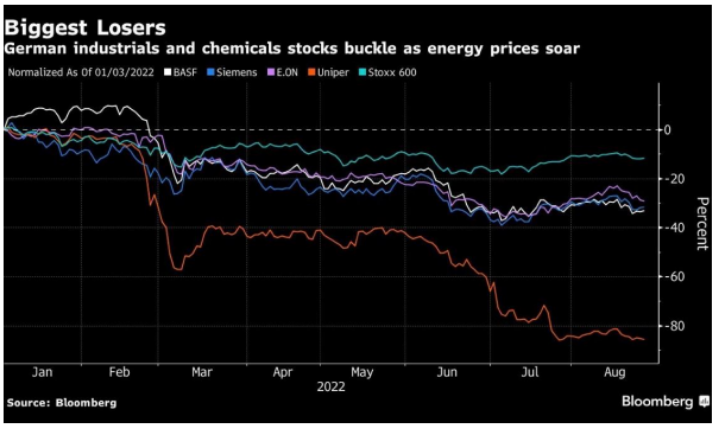

German equities of large-scale industrial producers have been hammered this summer as investors have concluded these companies face serious headwinds unless and until energy costs normalize (and prices are a LONG WAY from any semblance of normal).

This European market chaos likely leads to power rationalization and prioritization by government officials who, one would think, would place food production at the top of the priority list. What is the situation EU officials face regarding European oilseed processing capacity, import capacity (replacement for domestic production), and storage capacity (if a processor cannot receive a mature crop at harvest it has to go to storage or the crop will spoil)?

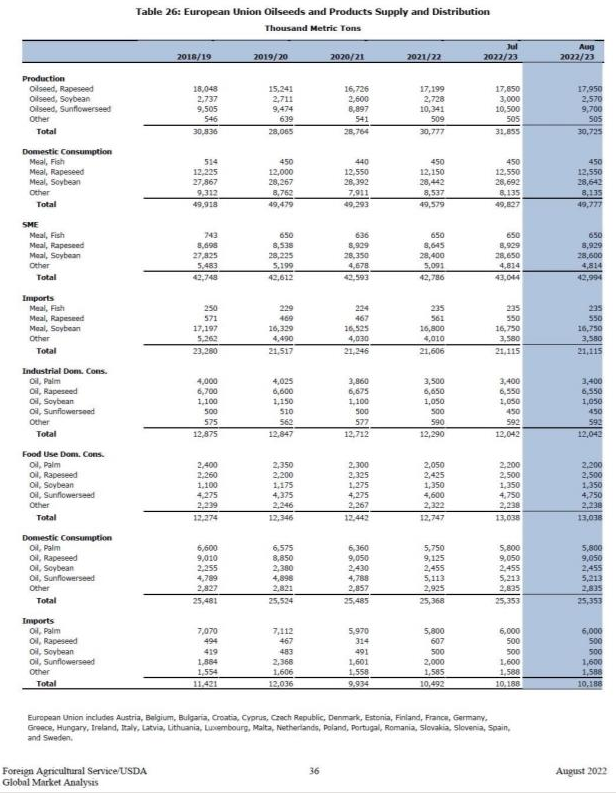

First, I want to provide a very brief backgrounder to put EU oilseed processing capacity into perspective. In its most recent forecast for European processing the USDA made no adjustment for the power crisis and kept processing forecasts within historic 5-year ranges. Is a change in perspective coming or have USDA economists simply assumed that food processing will remain a priority if/when power rationalization occurs? I don’t have a clue but I will certainly monitor the updated forecasts closely each month. The USDA produces detailed European oilseed analysis as part of its monthly Oilseeds World Markets and Trade and the August version appears on the next page.

The following table provides a general sense of the risks to European oilseed supplies. From the 50,000- foot perspective the USDA forecasts the European Union will consume 49.77 million tons of protein meal in the coming year; EU companies will process 17.95 million metric tons of domestic rapeseed, Europe’s primary oilseed, 9.7 million metric tons of domestic sunflower seeds, and 3 million tons of domestic soybeans and other seeds. The European Union will import 15.2 million metric tons of soybeans to process and import 16.7 million metric tons of soybean meal. In summary, for the purposes of producing protein meals the European Union must process 46 million metric tons of seeds, or, if power prices (or supply) curtail processing capacity, import a massive amount of protein meals to replace domestic production.

What about vegetable oils? Again, from the 50,000-foot level, the European Union consumes 25 million metric tons of vegetables oils (nearly half for industrial purposes and biofuels) of which 60% come from its domestic processing (rapeseed and sunflower seed) and 40% from imports, mostly palm oil.

Several questions emerge from that quick review. Clearly domestic oilseed processing is critical to food production in the European Union and would reasonably rank near the top of the list of industries that regulators and politicians would protect to ensure sufficient power supplies to operate (and to date the USDA forecasts appear to assume that to be true). Prices in European power markets have moved to extreme (unfathomable) levels and might it be that power supplies get curtailed even to the most critical industries as part of Europe’s rationalization? Could European authorities provide only 75% of the oilseed processing industry’s power needs, forcing processors to reduce domestic crush rates which would limit available supplies of meal and oil to European food, feed, and biofuel industries? What are the implications for even that level of reduction of available power and how can we as market observers “see” these events.

The first thing European consumers (food producers, livestock producers, biofuel producers) will do is reach for imports to replace lost domestic production, in effect buying protein meals and oils produced in countries whose utilities charge industry lower power rates so effectively Europe imports cheaper electricity. European consumers reaching for imports begs the question of whether European ports will have the power to operate all the conveyance that is part and parcel of the offloading of ships and the bulk transfer of meals and oils to storage for shipment via rail and truck to a consumers’ facility.

How will we see that European import activity to understand the impact from power prices to domestic oilseed processors? For US exports to Europe, we can see the details in the weekly export sales reports or if the transaction is large enough through a “flash” daily report from the USDA that occurs if a sale exceeds certain thresholds. Those export sales reports will be the best leading indicators (global players who execute the buy and sale of the oilseed products for import or for export obviously get a superior front row seat relative to the rest of us and will see the scenarios unfolding first). A “flash” would look like this head scratcher (camel’s nose under the tent?) that occurred three weeks ago:

Another source, but unfortunately a lagging indicator, is USDA monthly world agricultural supply and demand (WASDE) reports and filings from USDA agricultural attaches posted in Europe who provide input to the USDA and also file ad hoc reports (special situation) on supply and demand. If power issues curtail domestic production in Europe then USDA’s economists will necessarily adjust domestic processing levels lower and meal and oil imports higher, signaling that power curtailments are being taken into consideration for forecasting supply and demand tables. Leading private analysts in the oilseed space (I feel quite certain their phones are ringing off the hook with subscribers demanding some likely scenarios considering the spike in power prices) will adjust supply and demand factors much more rapidly than the USDA and may provide early clues to changes but they do not have the USDA’s resources and so markets will wait to see USDA confirm the private analysts’ projections.

If European consumers are importing meals and oils at significantly higher volume than forecasts it is because their domestic processing plants are running at reduced rates or potentially not at all. What happens to oilseed trade flows if the processor is not processing? In short, the interrupted trade flows become a real logistical challenge. Going back to our original detail on 46 million metric tons of annual processing, in round numbers that is .89 million metric tons of oilseed movement per week that heads to a processing facility by either barge, rail, or truck. If processors are not receiving oilseeds due to power constraints the seed must go somewhere and that somewhere is potentially available (conventional storage capacity) or needs to become available (non-conventional storage capacity). One way or the other the seeds need to be put out of harm’s way. Can European warehousemen and farmers carry the physical and financial load? Do European oilseeds spoil at a higher than average rate, reducing supply?

The European situation is extremely troubling and the ability of Europe to solve its power crisis is critical to prevent a food crisis. Go hungry or cold? Yikes. I will post regularly on this situation as it unfolds.

P.S. US soybean processing margins are soaring! Europe calling?