Insight Focus

- Importers of carbon-intensive materials to the EU will pay for emissions.

- The EU will assess the materials’ carbon content.

- Importers will need to buy sufficient CBAM certificates.

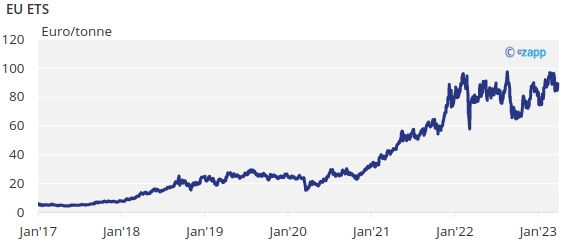

Europe’s Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) requires industrial companies to buy and surrender carbon allowances (EUAs) matching their emissions of greenhouse gases each year.

The cost of buying these EUAs forces enterprises to account for the climate impact of their operations and to undertake innovation and investment to reduce that carbon footprint. Data show that emissions from more than 11,000 installations across the bloc have fallen from more than 2 billion tonnes in 2008 to less than 1.3 billion tonnes in 2021.

But throughout the 18 years of the EU ETS, many industrials have enjoyed a free handout of EUAs, which helps protect energy intensive and trade exposed industries like steel, cement and chemicals from competition from countries where there is no carbon price.

Adding a carbon price of as much as €100 to the cost of making steel in Europe would put regional producers at a big disadvantage to producers in India or China, where no such cost exists.

The free allocation of EUAs addresses the risk of so-called “carbon leakage”, where production is offshored to lower-regulated jurisdictions in order to escape the costs of producing in the EU.

While much was made of the risk of carbon leakage in the early days of the EU, there is so far very little evidence that EU production has left the bloc due to the cost of carbon permits.

And the result is that since these protected industries have not had to fully internalise the cost of their climate impact, they have made relatively little progress in cutting their carbon emissions, compared to the power sector, which in many cases is abandoning fossil fuels in favour of renewable energy and even natural gas, which emits half as much CO2 as coal.

This is all set to change in the next few years after EU member states agreed last month to introduce a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM).

The CBAM will require imports of carbon-intensive materials – steel, cement, chemicals and more – to pay for the emissions embedded in their production. Using data gathered from producing plants around the world, the EU plans to assess the carbon content of every tonne of materials, and importers will need to buy CBAM certificates matching the assessed carbon content.

These CBAM certificates will be priced equivalent to EUAs in the bloc’s internal carbon market, though they won’t be tradable: any unused certificates will be redeemed by the EU.

The ultimate impact of CBAM will be to level the playing field between EU producers – who pay a carbon price – and non-EU producers who don’t.

This will also remove the need to hand out EUAs free of charge to European producers. Industrial companies across the bloc will then need to internalise the cost of their emissions and to invest in decarbonisation.

There is one key caveat: if a third country that supplies the EU has its own carbon pricing mechanism in place, then its exports to the EU could be exempt from CBAM, since its producers are theoretically subject to the same costs as EU companies.

The legislation specifies however that the “the CBAM should ensure that imported products are subject to a regulatory system that applies carbon costs equivalent to the ones that otherwise would have been borne under the EU ETS”.

The EU ETS market price currently stands at around €88/tonne, while the neighbouring UK ETS price is some €20 lower at the moment. These two markets are far ahead of the rest of the world in terms of price burden, and therefore it’s likely that imports from anywhere else would be subject to some level of CBAM levy.

How can importers prepare for CBAM? As mentioned, CBAM certificates themselves will not be tradable, but will nonetheless be priced at the equivalent of the average EUA auction price each week.

The legislation states that “in order to preserve its effectiveness as a carbon leakage measure and to ensure compatibility with WTO rules, the CBAM needs to reflect closely the EU ETS price. While on the EU ETS market the price of allowances is determined through auctions, the price of CBAM certificates should reasonably reflect the price of such auctions through averages calculated on a weekly basis.”

“Such weekly average prices reflect closely the price fluctuations of the EU ETS and allow a reasonable margin for importers to take advantage of the price changes of the EU ETS while at the same ensuring that the system remains manageable for the administrative authorities.”

This offers a hedging opportunity to importers, who could buy EUA futures to lock in the cost of their CBAM certificates. It’s also likely that some sort of price index or tradable instrument may be developed to mirror the weekly average auction price fluctuations, and offer importers a more efficient way to hedge their exposure.