Insight Focus

Emissions reduction takes a lot of work, but who gets the credit? Emissions are measured using “scopes” depending on how they are produced, and sometimes more than one party can claim the reduction.

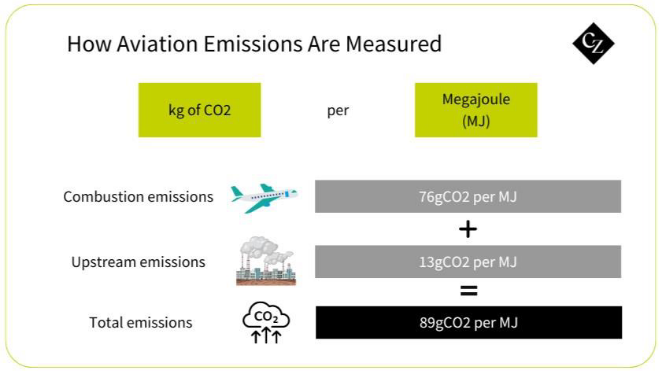

Last time, we broke down the emissions story into the fundamental numbers around how much carbon dioxide (CO2) is produced when jet fuel combustion occurs. We also discussed how, given that this release of CO2 is immutable, we can claim to be on a journey to net zero emissions while continuing to use jet fuel.

This time, we are going to look at the framework used for reporting CO2 emissions.

Heading

Remember that CO2 release during flight is almost completely independent of the provenance of the fuel, feedstock or processing route. It’s 76g CO2/MJ.

This number may be reduced only on a lifecycle basis — that is by using materials and processes upstream that reduce the 76g.

How this happens, and how this is calculated, depends on your position in the cycle – if carbon is reduced elsewhere in the jet fuel life cycle, can you claim that benefit? How can an airline claim the benefit of SAF when its real emissions don’t change and when the SAF producer is claiming that benefit?

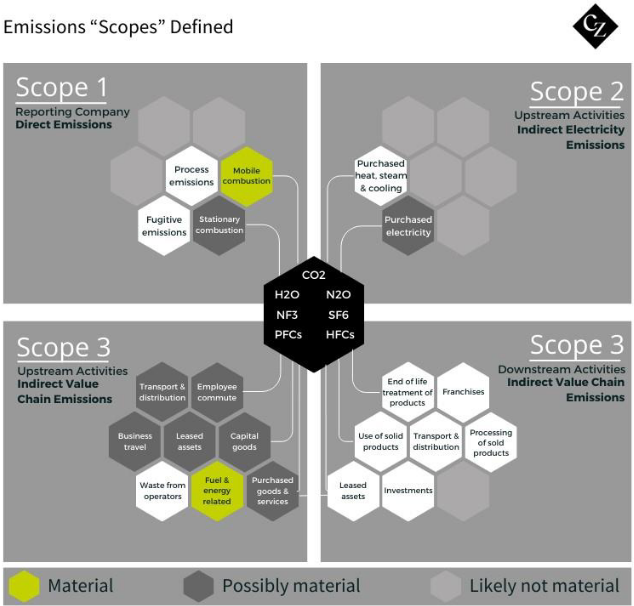

The answer is that emissions are defined according to who is responsible for them and are categorised according to ‘scope’. For a particular corporate entity:

- Scope 1 covers emissions that are directly released in its operation.

- Scope 2 covers emissions released by suppliers and third parties.

- Scope 3 covers emissions released by a third-party using products of the entity.

SAF Doubles Up on Reduction

So, if we take a look at an airline, the CO2 emitted during its flying operations are Scope 1. These exact same emissions for the fuel supplier are Scope 3. Note that Scope 1 emissions for airlines are by far the largest component of their emissions inventory.

If an airline reduces its emissions by, for example, fleet modernisation, its Scope 1 emissions reduce, determined by measurement and analysis of real consumption figures.

If an airline uses some SAF, the airline’s Scope 1 emissions are adjusted according to the proportion of SAF deployed. This is subject to factor reported by the supplier, and verified by a standards agency, that highlights the true emissions reduction inherent to that batch of SAF. Similarly, the airline’s Scope 3 emissions will be adjusted according to the amount of CO2 reduction effected by the supplier in the production, transport and processing employed to manufacture the SAF.

So, for the airline, SAF impacts both Scope 1 (because the CO2 is partly recycled) and Scope 3 (to account for the supplier’s use of renewable electricity).

For the SAF supplier, Scope 1 emissions are associated with the production of SAF from its feedstock, Scope 2 emissions are associated with the generation of electricity consumed in the production of SAF and Scope 3 emissions are linked to feedstock cultivation and transport and the combustion of the SAF produced.

This may seem complicated but in reality, it’s a robust and straightforward model – next time we’ll run through some examples.