- Demurrage and detention are essential tools to ensure the container industry operates smoothly.

- But recent snags in the supply chain mean they are pushing up costs without raising efficiency.

- The issues caused by these fees is likely to cause the price of food to rise further.

Inflation has been blamed for much of the consumer price pressure being felt today. But the truth is, inflationary effects are being amplified by several factors. One of these is increased shipping costs. While at first glance it may look like it’s caused by staffing and vessel shortages, this is only component. Recently, demurrage and detention have been causing havoc in the container market.

Demurrage Explained

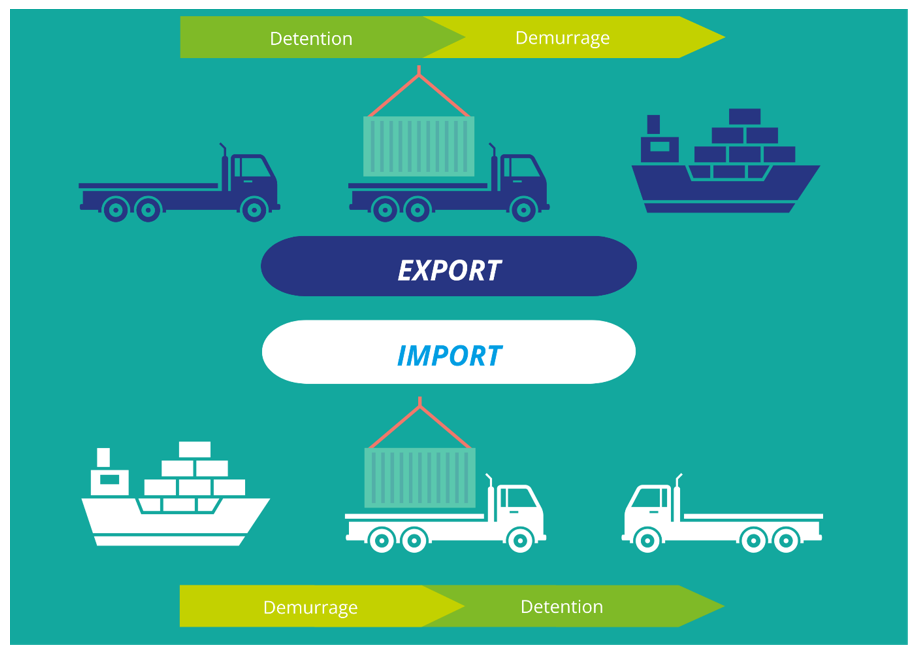

The terms “demurrage” and “detention” both refer to a specific stage within the shipping supply chain. The demurrage period lasts from the vessel’s arrival at the port until the container on board is loaded onto a truck and moved inside the terminal. From this point, the” detention” countdown starts until the empty container is returned to the carrier.

These stages generally last for around 12 days in total. This allows haulage firms time to transport their cargoes, discharge with the customer and return the empty container to its owner. If a container is not returned to the owner within the allocated time, fines begin to rack up. The same principle applies in the opposite direction.

Demurrage and detention fees were designed as a sensible stopgap for the container industry. It meant that those companies that owned the containers could recoup some of the expense of containers not being returned on time. It also served as an incentive that would make the supply chain more efficient because nobody wants to pay extra fees for running late.

The concept of demurrage seems to have worked well until the global logistics logjams of the past few years developed. With ports facing unprecedented congestion, widescale staffing shortages and in some cases labour disputes, there are stumbling blocks across the logistics chain.

Port Congestion Slows Container Flow

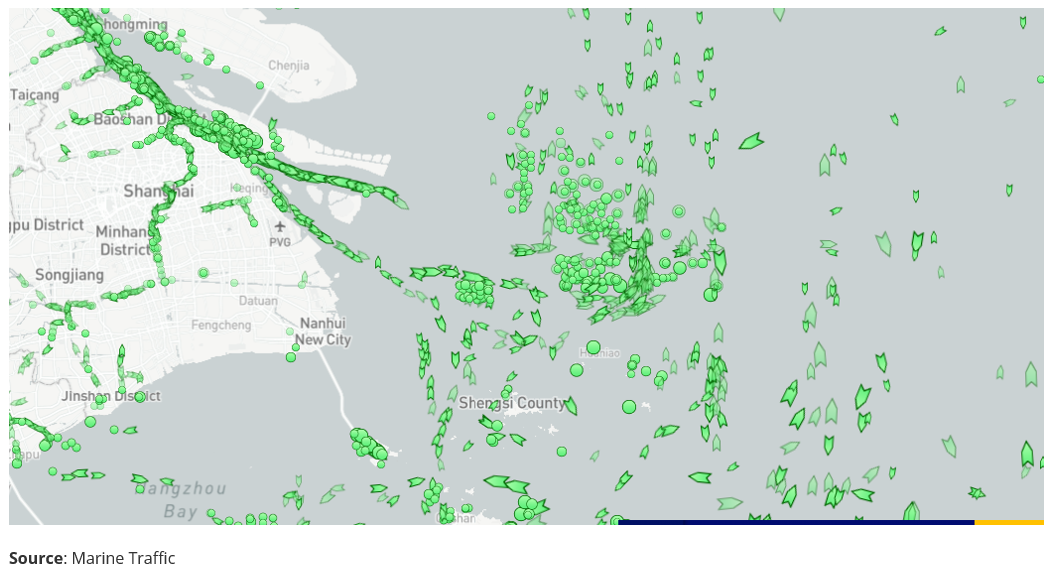

The issue begins with port congestion. Shanghai, the world’s busiest container terminal, is still facing huge queues of vessels trying to enter the port. According to data from project44, the current import dwell time is 7.66 days, meaning ships generally need to wait this long to berth and unload cargoes.

Any delays at individual ports have a knock-on effect on all container traffic globally. At major container terminal Rotterdam in the Netherlands for example, export dwell times are coming in at 5.83 days, while berthing dwells are 1.33 days. At the UAE’s Jebel Ali, the export dwell is 6.2 days compared with a 1.38-day berthing dwell.

This indicates that containers are left waiting at ports for days for delayed vessels. Ever larger ships are playing a role in this as there tends to be a longer backlog if these ships are delayed. With huge inventories building up in warehouses, these marine terminals need to free up space.

When Demurrage Goes Wrong

Containers belong to ocean carriers and leasing companies, and different types of containers can only be returned to certain marine terminals at specific times. In many cases, appointments need to be made for returns. But with staffing shortages, high inventories and ports working to high capacity, these appointments are few and far between.

Given the environment, there have also been reports of “appointment hoarding”. Since January, APM Terminals has reported these incidents at its Port Elizabeth terminal in South Africa. The appointment windows are often fully booked but the terminal receives just 54% of what was actually booked.

Sometimes, in a bid to clear container backlogs, marine terminals can insist that trucking companies only return containers under a “dual transaction” – returning one container while picking up another cargo. The problem is that the trucking firm may not have a client with a load at that port.

In most cases, it is the responsibility of the cargo owner to pay demurrage and detention fees, but it is the haulage companies picking up the cargoes that must directly pay the fees on their behalf. Refunds for these fees can take months to process – and that is if the cargo owner takes responsibility for the fees at all. Given the recent delays, it can be difficult to pinpoint which party is responsible for generating the fees.

The result is that trucking firms are often stuck with a container they are unable to return, and the detention countdown continues ticking, generating daily fees. If containers are returned very late or fees aren’t paid, companies can receive a “shut out” notice from the carrier barring it from picking up any of its cargoes.

Many trucking firms are now reluctant to take this risk or are commanding high premiums from cargo owners to cover the demurrage and detention fees.

Situation Creates Truck Shortage

The situation faced by importers and exporters is becoming a self-fulfilling cycle. Haulage firms that are unable to return containers can find that much of their fleet is out of commission. This is because the steel chassis of the trucks are tied up holding empty containers.

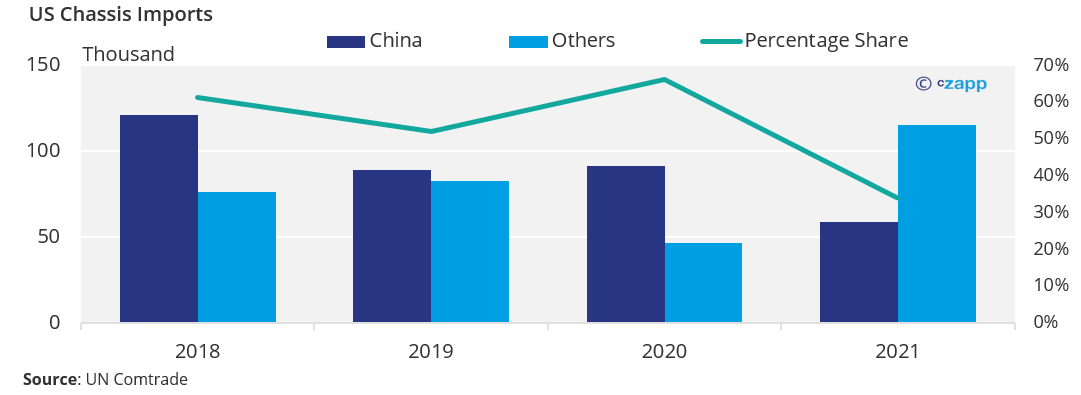

Prior to this, there was already a chassis shortage in the US, predicted to last until 2023. In 2021, the US applied anti-dumping and countervailing duties of 200% on Chinese-made chassis, generating a scramble for a new supplier. But the problem is that China manufactures approximately 85% of all intermodal truck chassis globally.

This in turn creates a tighter freight market, which means that more and more goods offloaded at ports are being directed to storage at the marine terminal rather than being loaded directly onto trucks. This is only exacerbating the overcrowding at port storage facilities.

Food transportation is particularly vulnerable to these delays due to spoilage. If food exporters and importers cannot persuade trucking firms to pick up loads at the port, there is huge risk of economic losses. This seems ever more likely given that it is no longer worthwhile for trucking firms to accept these orders. Cargo owners must decide whether to pay a premium on trucking or huge storage and demurrage fees.

Railway Demurrage in the Crosshairs

It is not just marine terminals and ocean liners. Railways can also charge demurrage fees. If a shipper uses a container belonging to a rail operator for longer than the agreed time, the operator is entitled to charge. But often there is disagreement over who is responsible for delays, especially in instance of reduced rail service.

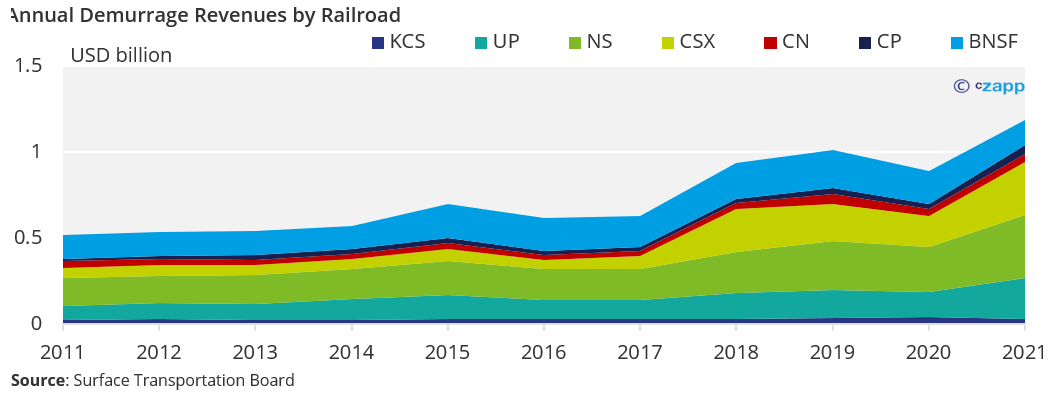

Across the US, the demurrage fees can vary depending on the rail operator, container dwell time and facility. The cost can range from USD 75 to USD 500 a day. And as these charges have become more common due to congestion, rail revenues have shot up.

The US Surface Transportation Board (STB) stepped in this January to address the issue. Now, under new rules, Class 1 railroads must bill the shipper directly, instead of passing the charge onto terminal operators or third-party logistics operators. This makes it easier for cargo owners to dispute charges.

Ocean Liners Bite Back

Now, just like the railroad industry, the ocean liner industry has come under intense scrutiny. In the US, the Federal Maritime Commission (FMC) launched an investigation into the application of “unjust and unreasonable” demurrage and detention fees.

In February, the Ocean Shipping Reform Act was introduced and later passed in the US Senate. Although it did not outlaw the charges altogether, the legislation shifted the burden of proof in disputes from shippers to carriers, which opens the door to more complaints being filed against ocean liners.

Some argue that the ocean liners have been capitalizing on the shipping logjams, using them as an opportunity to bump up profit margins.

However, the World Shipping Council argues that the charges are necessary to incentivize the efficient operation of container terminals as global imports surge.

“There is no dispute that carriers, after two decades of low or no margins and cheap and abundant capacity for shippers, are actually making profits,” it said in a statement. “But as long as America’s ports, railyards and warehouses remain overloaded and unable to cope with the increased trade levels, vessels will remain stuck outside ports to the detriment of importers as well as exporters.”

Concluding Thoughts

- Although shipping rates are coming down, the current demurrage situation is leading to inflationary pressure.

- Often, these extra charges need to be passed on to the end customer.

- The situation is becoming a self-fulfilling cycle with lower capacity and the inability to return containers, tying up yet more availability.

- Small and medium trucking firms are struggling and some going out of business, further tightening supply.

Other Insights that may be of interest

What the Energy Crisis Means for Inflation & Commodities

Interactive Data Reports that may be of interest …

Consecana Panel

CS Brazil Weather Update