Insight Focus

- EU aims to cut fertilizer use by 20% and pesticide use by 50% in Farm to Fork strategy.

- Reductions in inputs is already happening on a per capita basis.

- Success could reduce risk and raise margins for farmers.

The European Union’s Farm to Fork strategy was launched in May 2020 under the framework of the European Green Deal.

The strategy sets out several pledges and targets for the EU to reach by 2030 with the goal of creating a more sustainable, environmentally friendly food value chain.

While some proposals are more specific than others, the Farm to Fork strategy is an ambitious plan but it has invited some criticism. Over this eight-part series, we aim to provide you with a greater understanding of the policy’s implications and how it might affect your day-to-day business.

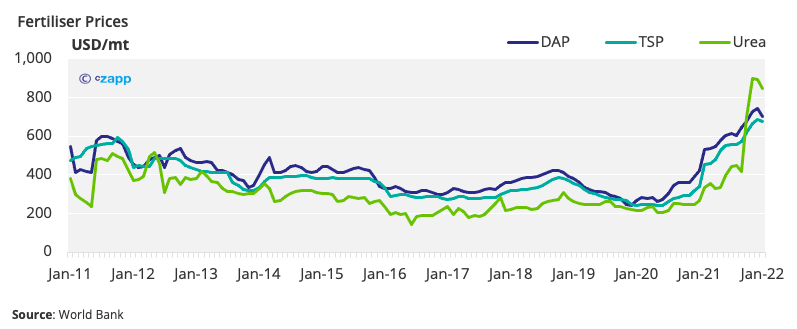

Input Costs are Rising

Recent rises in oil and gas prices due to COVID-19 reopening, difficulties increasing production and the Ukraine crisis have in turn pushed fertiliser prices up.

This is exacerbated by Russia’s ban on ammonium nitrate exports, since it’s the EU’s largest fertilizer supplier.

Given that farmers are feeling the pinch, now might be the time for the EU to start working toward its goal of reducing fertilizer and pesticide use. But just how much money might be saved?

Financial Implications

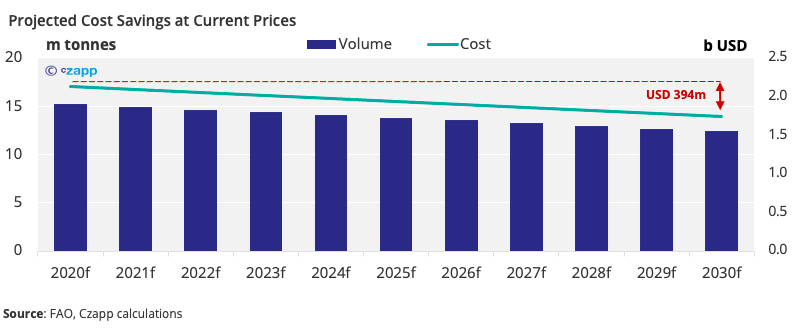

The EU’s goal is to reduce fertilizer use by 20%, which would mean a drop in consumption by about 3m tonnes per year.

At current prices, this could equate to savings of about USD 394 million.

The Pesticide Story

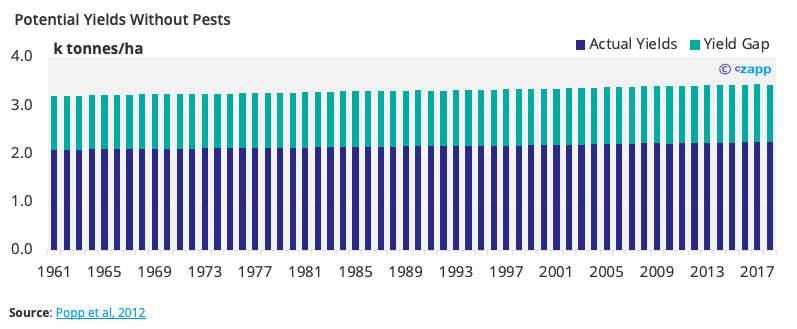

If fertilizer use can be reduced, it could be potentially lucrative for farmers. But what about pesticides? Globally, about 35% of potential crop yield is lost to pre-harvest pests and disease.

Of the USD 1.5 trillion of global attainable crop production, just USD 950 billion is actually achieved each year. Without crop protection, there would be an additional USD455 billion lost to pests, disease, and weeds.

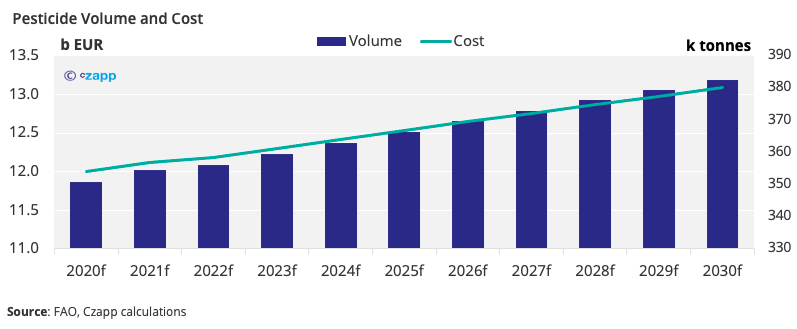

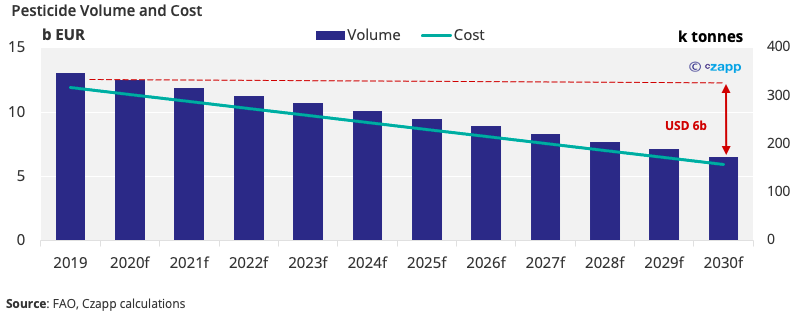

With the EU buying about EUR 12 billion worth of pesticides in 2019, the industry has the potential to cost EUR 13 billion by 2030.

If the EU achieves its goals of reducing pesticide use by 50% in this time, though, the cost would be far lower (about EUR 6 billion).

What are the Alternatives?

So, we know we have to address inputs, and we know there’s a potential financial benefit, but how do we do it? There are several ways in which this can be done.

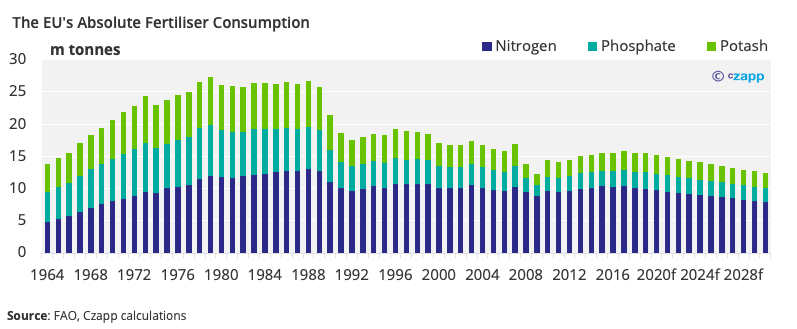

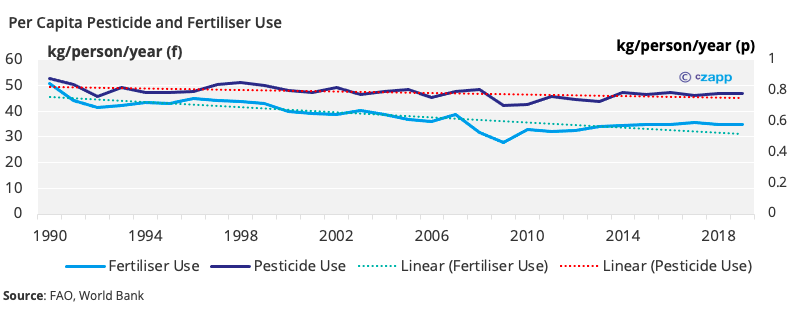

Some of the required actions are already taking place. The truth is that fertiliser and pesticide use has been slowly reducing in the EU over the course of several years. While, on the surface, it looks like their use has accelerated, on a per capita basis, there’s actually less fertiliser and pesticide use today than there was in 1990.

However, more still needs to be done. Integrated pest management strategies and nutrient management action plans are a good place to start. Synthetic fertilisers can be replaced by organic fertilisers, including use of organic waste already available on farms. Given that the EU already has an issue with food waste, there’s an opportunity for a circular economy to emerge.

Another option is the increased production of nitrogen-fixing legumes. Certain legumes, such as peas, clovers and beans can stimulate the bacteria that lives in soil, which means planting them can act as a natural fertilizer. However, given that agricultural land is already scarce, this option is unlikely to be widely scalable.

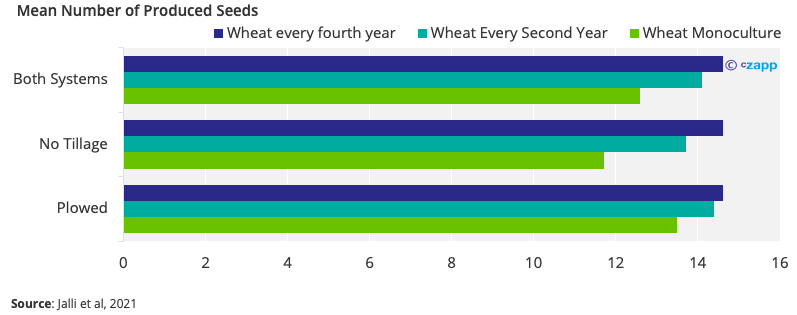

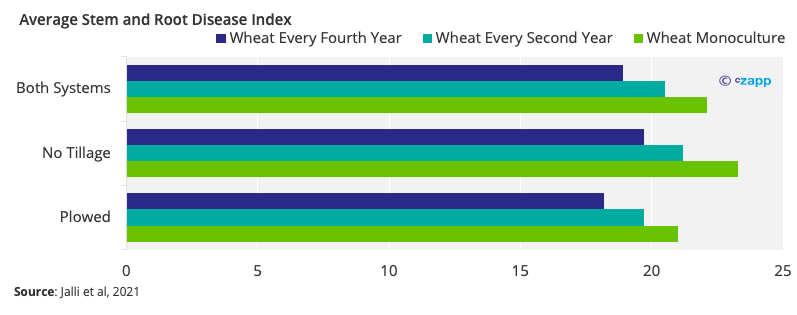

Crop rotation has been found to increase yields while limiting damage to soil. We wrote about this in more detail here.

Crop rotation can also increase the number of seeds produced for future harvest, which in itself increases productivity and reduces costs.

It can also lower the prevalence of pests and disease, particularly when fields are ploughed. This also addresses concerns related to pesticide reduction.

Concluding Thoughts

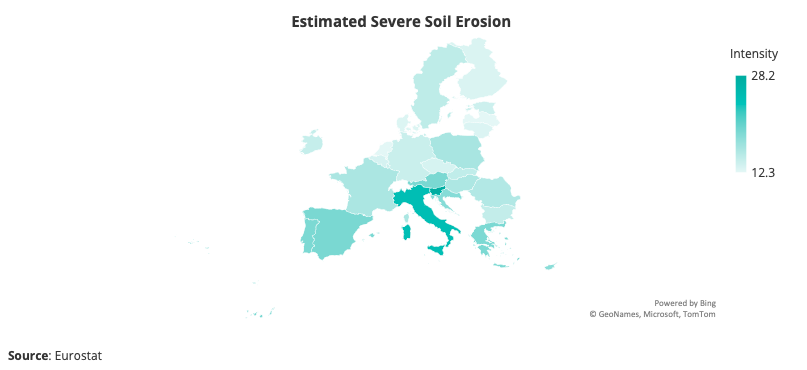

Reducing dependence on pesticides and fertilizers is especially important given the current levels of soil erosion in the EU. Some agriculturally intensive countries, such as Italy, are seeing significant levels of severe erosion.

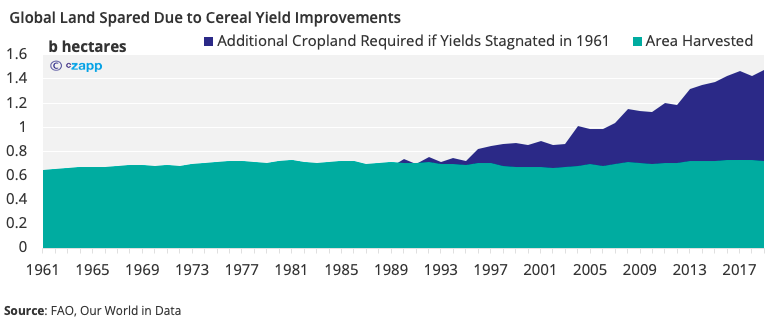

Fertilizers and pesticides are essential to raising agricultural yields. In a business-as-usual scenario, we’d have needed double the agricultural land we use today to generate the same yields had it not been for the development of synthetic fertilizers. But even the current agricultural land volume is untenable.

But just because synthetic fertilizers and pesticides were vital in the past, that doesn’t mean agriculture must continue to rely on them. Given the amount of research and development and investment in new technologies, many more effective cultivation techniques are now emerging.

So, reduction in fertilizers and pesticides doesn’t have to equal a compromise in yields. And most of the EU’s goals are achievable in a way that doesn’t need to negatively impact soil quality, yields and can actually generate financial benefits.

With the right incentives and investment, dependence on synthetic farming inputs may not disappear but it can certainly be scaled back significantly while the industry continues to feed a growing population.

Other Insights That May Be of Interest…

Is the EU Focussing on the Right Area of Food Waste?

Going Organic Could Curb Fertiliser Price Rise