Insight Focus

- The events industry is expecting a post-pandemic boom in 2022.

- Will events push forward with pre-pandemic plastic-free commitments?

- Or could a greater recognition of value in plastic waste prompt more recycling, rather than elimination?

Having been decimated by COVID-19, the events industry is expecting a post-pandemic boom in 2022.

Despite the recent Omicron outbreak, many large music festivals, concerts, and sporting events have already sold out at astounding pace as pent-up demand is unleashed. This is good news for beverages and associated plastic packaging consumption. Or is it?

Pre-pandemic, many events were beginning to make ambitious commitments to going plastic free. But as the events industry prepares for a bumper 2022, are plastic use commitments being kept in mind, or are single-use plastics now considered acceptable as a sanitary solution in the wake of the pandemic?

Plastics in Events

On a global basis, an average stadium hosting around 300 events per year – or about six per week – uses 5.4 million single-use plastic cups and bottles. This creates about 63.75 tonnes of plastic waste each year. As of June 2020, there were around 5,735 stadiums in the world, according to The Sporting Blog. This would equate to over 365k tonnes of plastic waste at sporting events alone.

A Turning Tide

ASM Global is a US-based operator of over 300 stadiums, amphitheatres, convention centres, arenas, and theatres all over the world, with 2.7 million seats under management and hosting 160 million guests each year.

This month, the company launched a new sustainability program that aims to reduce waste. The measures include eventually getting rid of single-use plastic bottles at all its venues.

Other events organizers have made previous commitments to reducing their use of plastic. In 2019, the world’s largest festival organizer, Live Nation, committed to eliminate single-use plastics from its venues by 2021. Fellow UK festival, Glastonbury, made a similar pledge, which could result in the elimination of 1.3 million plastic bottles a year.

According to representatives from Glastonbury, the ban on single-use plastic bottles will remain for Glastonbury 2022. The music festival, which attracts over 200,000 revellers, will again be encouraging people to bring reusable bottles to use at hundreds of free water taps around the site, whilst also selling water and soft drinks in cans.

Plastic Alternatives

Every year, in Munich, Oktoberfest draws crowds of up to 6 million who consume about 8 million litres of Bavarian beer.

But even as far back as 1991, the German city has been conscious about plastic use at the event and the administration banned the use of disposable cups and plates. This change reduced waste by more than 90%. The beer is instead served in traditional beer steins – although these weigh up to 1kg and can easily be broken at boisterous events.

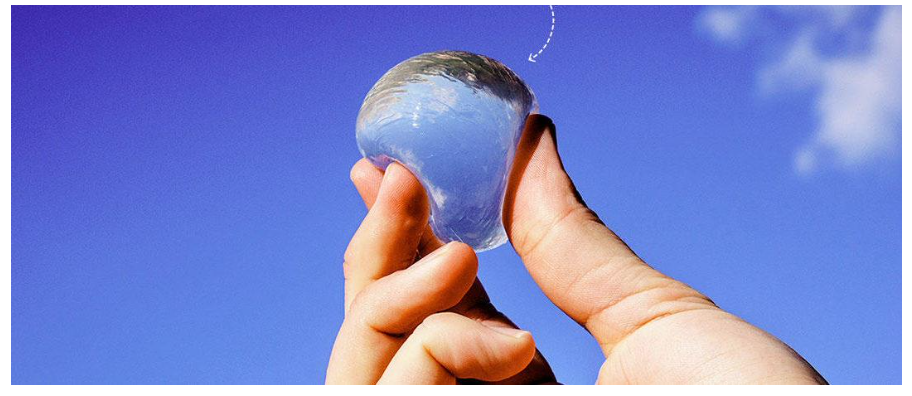

Another potential alternative to plastic bottles was adopted at the 2019 London Marathon, where edible seaweed pods were handed out instead of water. The Ooho pods produced by Skipping Rocks Lab can be bitten to release the liquid inside. The capsules can then be digested or discarded. The pods replaced 200,000 plastic bottles of the over 900,000 bottles typically used during the annual event. Organizers collected the remaining 700,000 bottles to process in a closed-loop recycling system.

But alternatives do not need to be all bad for plastic manufacturers. In the world of sport, the Rugby Football Union has implemented a plastic cup deposit system at the Twickenham stadium in the UK. Patrons can pay a £1 deposit for a plastic Ecocup, which can be refilled throughout the event. They can then choose to either return the cup in exchange for the deposit or take the cup home, forfeiting the money. The scheme was based on the success of a similar returnable cup program during the UEFA Euro football tournament in 2008.

No Viable Alternatives

Many events, though, are continuing to use plastic, especially in developing countries, where the cost of plastic alternatives tends to be prohibitively high.

Brazil’s Carnival, which takes place in February each year, draws in 1.9 million tourists and generates about $1 billion in revenues each year. In 2019, the festival generated 1,227 tonnes of waste, although how much of that was plastic is unclear. So far, there have been no concerted efforts to address plastic waste at this major event.

In India, despite a 2018 plastic ban in the city of Kolhapur, the amount of plastic waste generated during the annual Diwali festival that year almost doubled. A federal ban on most single-use plastics will come into force on the 1st July 2022, which may force event organisers in the country to rethink their approach to plastic.

COVID-19 has also caused an unexpected hitch in plastic reduction goals. Every year, in Thailand, tourists flock to Kho Phangan Island for the New Year Full Moon Countdown party. Normally, drinks are served in plastic buckets, which are collected by locals, sanitised, and sold back to bars. But this year, COVID-19 has caused the authorities to introduce a new rule banning the reusable buckets in favour of single-use plastic cups.

A New Plastic Collection Opportunity

A world of events without any form of plastic may be out of reach right now but that doesn’t mean there are no opportunities to be found. In fact, given the current critical shortage of RPET, these large-scale events could provide the perfect opportunity for organisers to collect plastic at scale and sell it back to beverage manufacturers who are scrambling for the material.

Selling reusable bottles and cups at reasonable prices and implementing plastic drop-off sites could be relatively lucrative for event’s organisers.

The Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) recently partnered with waste management firm, Geocycle, to funnel the two tonnes of waste generated from the first India vs. New Zealand test series match in November through Geocycle’s safe waste management system.

And during the annual Hajj to Mecca, Saudi Arabia plans to welcome 30 million pilgrims by 2030. In 2018, more than 42k tonnes of waste were generated, so authorities began to separate the waste collected on the site. The plastic can then be more easily channelled to recycling routes.

Concluding Thoughts

- It’s clear that underlying a potential events industry revival in 2022 is a continued move towards greater sustainability.

- Given the continued growth in anti-plastic sentiment since 2019, a certain degree of plastic demand destruction is expected. And, whilst many will embrace the ‘Reduce’ element of the ‘Reduce, Reuse, Recycle’ mantra by banning plastic cups and bottles, others will strike an important balance across all three Rs.

- Greater public understanding around recycling and the Closed Loop concept, and recognition of the value behind waste plastic streams, means many events will be embracing improved collection systems rather than simply banning plastics.

- With recycled plastic prices at eyewatering levels, plastic waste from many larger events could also become an important revenue steam for organisers. Major beverage brands could increasingly seek to work alongside organisers and return bottles back into their own systems.

Other Insights That May Be of Interest…

Europe’s PET Supply Worries Ease as Omicron Hits Consumer Demand

The War Against Plastics Enters its Next Stage

Czapp Explains: The Best Countries for Plastic Packaging Recycling