Freight Course Overview

Welcome to the fourth part of Czapp’s course on freight.

In the first episode we looked at the different ways that cargo can be moved through supply chains around the world.

In the second, we looked at the different participants in the drybulk freight market.

In the third we looked at the ships themselves.

- Types of Freight

- Drybulk Ocean Freight: Who Does What?

- Drybulk Vessels, Cargoes and Routes

- Drybulk Freight Contracts

- Freight Costs and Price Risk Management

- Container Freight

Now we will look at the paperwork involved. “Looking at paperwork” sounds deeply unpleasant, but we’ll try to avoid putting the ‘dry’ into ‘drybulk’.

Source: Shutterstock

Let’s say you need to ship something from A to B. How do you guarantee that what you want to happen will happen? You need a contract which can be enforced.

Here are the important documents which facilitate almost all bulk international trade.

Contract of Affreightment

A contract of affreightment (COA) is a legal agreement between a ship owner/operator and charterer. The ship owner agrees to allow the charterer to use some or all of the vessel to carry cargo for a specified time or voyage.

The charterer agrees to pay a specified price for this service: the “freight”.

The COA will specify that the ship provided will be seaworthy, that the shipowner will not deviate from the specified route without agreement of both parties, that the charterer won’t ship dangerous goods and that any ports nominated must be safe.

There are two major types of COA which are commonly in use: a charterparty and a bill of lading. Let’s look at both.

Charterparty

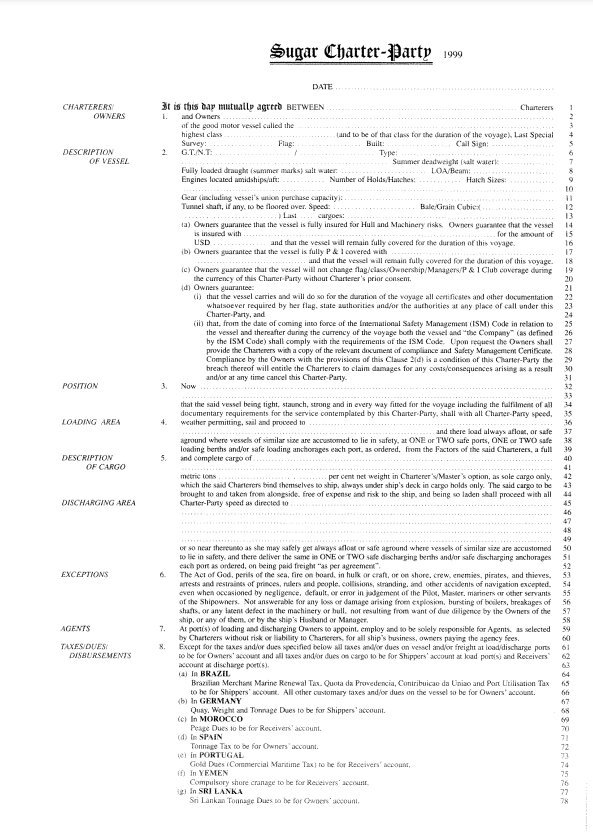

This is a maritime contract between a ship owner and a charterer to hire a ship to carry cargo for one or more voyages for a specified amount of time.

It should clearly set out the responsibilities of the ship owner and the charterers, so that any disputes that may arise will be settled in a court of law with reference to the terms agreed in the charterparty.

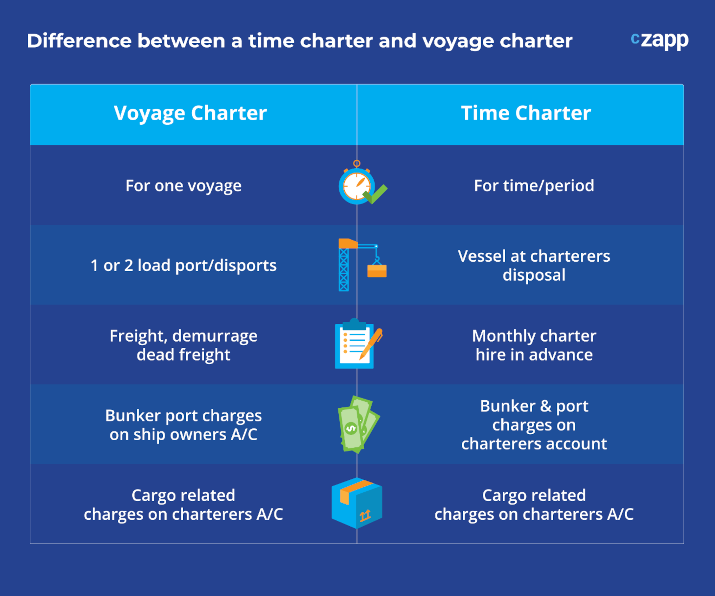

In a time charter a vessel is hired for a set amount of time. The ship owner still manages the vessel, but the charterer gives orders for how the vessel is used and may even choose to sub-charter the vessel. The contract will specify where the ship is ultimately redelivered to the owner at the end of the contract. Freight is paid to this point. This is analogous to a person renting a car.

In a voyage charter, the charterer hires the vessel for a single named voyage carrying a specified cargo for an agreed freight. The ship owner provides the master, crew, bunkering and supplies. This is rather like a pedestrian hiring a taxi.

Two further types of charterparty are less commonly used: bareboat charter, where the charterer effectively acts as the shipowner for a specified period of time, and a lump sum contract, where the owner carried a specified cargo for a fixed price.

A charter party is not a transferable document, nor does it specify ownership of the cargo. These details are found in the bill of lading.

Bill of Lading

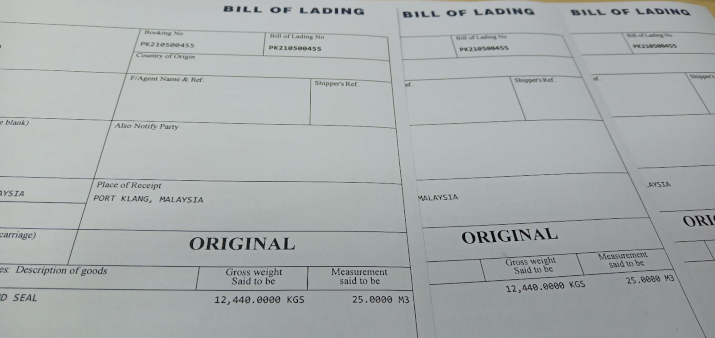

A bill of lading (BL) is a receipt for a cargo placed on a ship. It therefore contains all necessary details about a specific shipment.

The master of the vessel or the agent for the shipowner signs the BL to acknowledge the shipping of goods and the terms under which the cargo was carried. It is required for cargo movement.

Source: Shutterstock

A BL not only serves as a receipt of cargo. It also acts as a title document for the cargo and a commitment between the cargo carrier and the exporter. You may recall a charterparty governs the relationship between the shipowner and charterer. When the exporter and charterer are the same party, the charterparty is the dominant contract and the BL serves solely as receipt and document of title.

A BL can also act as evidence of a contract of carriage as the activities it describes must have been agreed between the shipper and exporter.

BLs were originally used centuries ago to prove that cargo expenses were paid and as proof that the cargo was really on board in the event that a ship was lost at sea. In time they evolved to become a negotiable property title as well as a cargo receipt.

A clean bill of lading is issued when there are no discrepancies between the goods as described by the shipper and the actual goods shipped. A dirty bill of lading (or claused bill of lading) can be issued if the goods ultimately loaded differ in quantity or quality from the goods as described by the contract. In this case the bill of lading can legally be rejected by the buyer’s bank or price terms may be renegotiated.

If goods can’t be examined, for example if the goods are shipped in a sealed container, the carrier can issue a “said to contain” (STC) bill of lading. This safeguards the carrier in the event that the seller/shipper has declared the wrong information on the BL.

The release of the BL to the intended recipient of the goods indicates a transfer of ownership. The BL is therefore often held until final payment is complete. Bills of lading are one of three documents used to ensure that exporters receive payment and importers receive goods. The other two documents are a policy of insurance and an invoice.

INCOTERMS

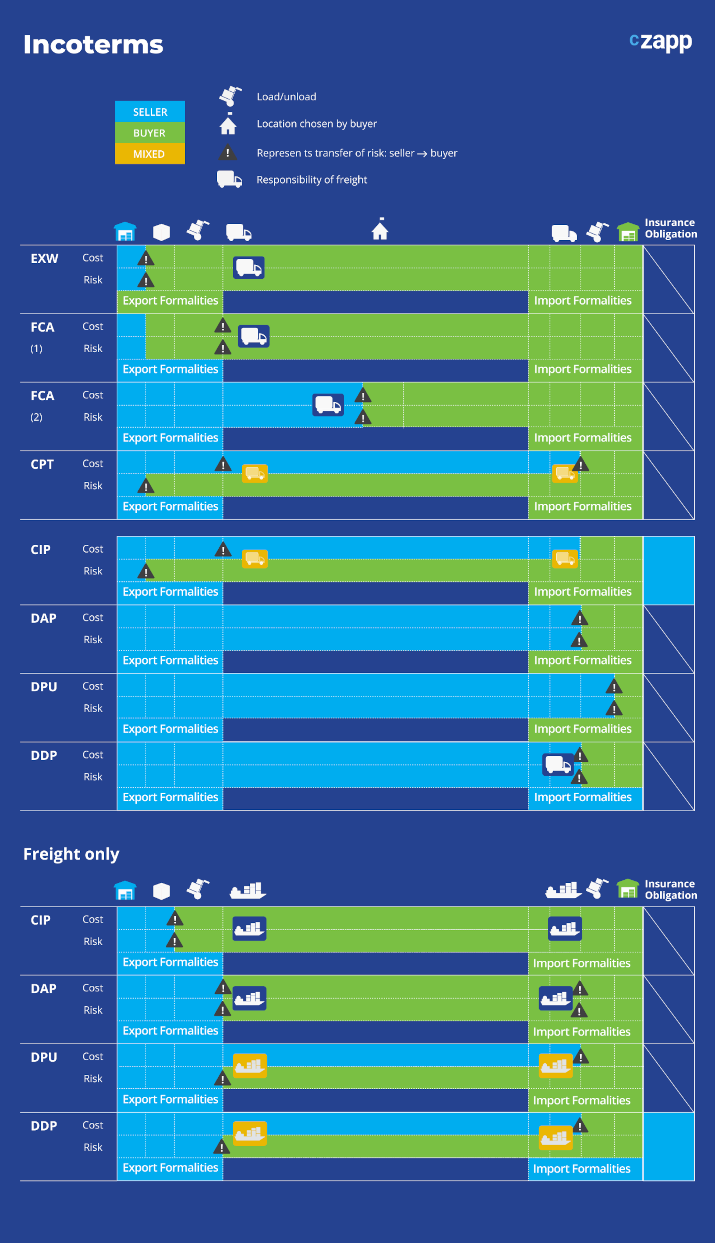

INCOTERMS (International Commercial Terms) are a set of commercial terms published by the International Chamber of Commerce. They can be used to promote clarity and completeness in commercial contracts, hopefully reducing legal complications.

They determine the moment where transfer of risk takes place from seller to buyer, the reach of price, the place of delivery and which party should arrange and pay for transport, insurance and customs clearance.

Here are the most common terms:

EXW – Ex-Works

The seller makes the goods available at their premises.

The buyer is responsible for collecting the goods from the seller and accepts all onward arrangements. The buyer accepts all costs, risks and liabilities associated with loading and moving the goods to destination.

The buyer therefore has complete control over shipping of the goods.

FCA – Free Carrier

The seller is responsible for the goods, including costs, up to delivery to the buyer’s chosen carrier at a named location – often a terminal or transport hub or freight forwarder’s warehouse. The seller is also responsible for export clearance.

The buyer is then responsible for moving the goods to destination.

If the named location is the seller’s place of business, then they are responsible for the loading of the goods. At all other named locations the buyer is responsible for loading.

FAS – Free Alongside Ship

The seller is required to place the goods alongside the carrier vessel at the port of export. The seller must arrange export customs clearance and bears risks and costs up to that point.

The buyer must arrange nomination of a suitable vessel and is responsible for loading the goods onto the vessel, and all onward movements.

FOB – Free On Board

The seller delivers the goods to the buyer on board a vessel nominated by the buyer at the port of export. Transfer of ownership commonly occurs at the point where the goods cross the ship’s rail.

The seller also arranges export clearance.

The buyer is responsible for the goods from the point they are loaded onto the ship.

FOB ensures that importers do not have to arrange logistics in the country of origin, but still retain control over costs of moving goods to destination.

CPT – Carriage Paid To

The seller bears all costs for transporting goods to their chosen freight carrier at a named port. The seller arranged export clearance.

The buyer arranges insurance for the goods and bears costs and risks from the time the goods are transferred to the freight carrier.

CPT is commonly used when there are multiple carriers in a transaction.

CIP – Carriage and Insurance Paid

The seller has the same responsibilities as in CPT, but must also arrange for insurance for the goods to destination.

DAP – Delivered At Place

The seller delivers the goods (and transfers the risk) to the buyer when the goods are placed at the disposal of the buyer on the arriving means of transport ready for unloading at the named destination.

The buyer then arranges unloading of the goods.

DPU – Delivered at Place Unloaded

The seller delivers the goods and transfers the risk to the buyer when the goods are unloaded at the named destination.

DPU is the only Incoterm which results in the seller paying for unloading at destination. Contracts should therefore be as specific as possible about the exact nature and location of unloading.

DDP – Delivered Duty Paid

The seller is responsible delivering the goods to the buyer on the arriving means of transport at a named destination, cleared for import with all applicable taxes and duties paid.

The buyer is responsible for unloading the goods.

CFR – Cost And Freight

The seller delivers the goods on board a vessel at the named port of destination.

The buyer assumes bears all risks for loss or damage once the goods are on board and so must arrange insurance. The buyer also has responsibility for local charges, taxes and duties and unloading.

The buyer therefore has little to no control over the shipping process and associated charges.

CIF – Cost Insurance and Freight

The same shipping terms as CFR, but the seller must also arrange insurance for the goods to destination.

Czapp Explains – Freight series: Types of Freight