Freight Course Overview

Welcome to the second instalment of Czapp’s course on freight.

In the first episode we looked at the different ways that cargo can be moved through supply chains around the world. Now we will examine the drybulk freight market in more detail.

- Types of Freight

- Drybulk Ocean Freight: Who Does What?

- Drybulk Vessels, Cargoes and Routes

- Drybulk Freight Contracts

- Freight Costs and Price Risk Management

- Container Freight

As always, we’d like this course to be as fun as education on freight can be. Please send us your feedback to help us improve future editions.

Drybulk Ocean Freight Basics

Bulk freight means that the cargo is carried loose in the ship’s hold. You don’t win any prizes for guessing what “ocean freight” means.

Source: Shutterstock

Drybulk ocean freight is suitable for transporting dry goods which will be used industrially. Placing items directly into a ship’s hold means they will no longer be food grade, or pharmaceutical grade, or any other grade, no matter how clean the ship’s hold is! Shipping this way would also be a messy disaster for transporting liquids or gases.

Source: Shutterstock

While it’s possible to move drybulk cargoes by rail, road or barge, ocean freight accounts for 99% of this market in terms of tonnage moved per year, and so this is where we will concentrate our attention.

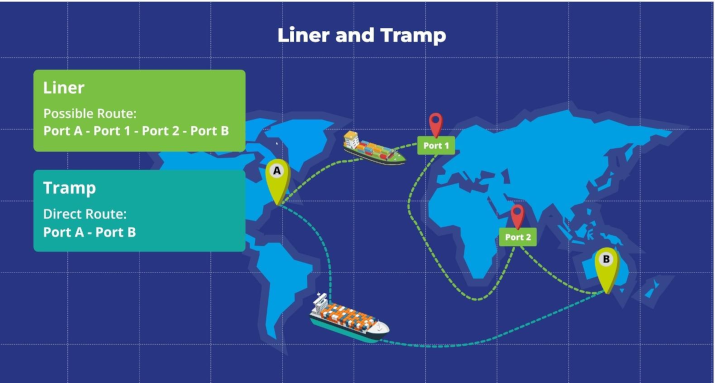

Drybulk cargo tends to move by tramp business, not liner.

Tramp business is where owners or operators offer their vessels for hire to carry cargoes between any suitable ports in the world, according to a bespoke contract called a charter party. Chartered ships go anywhere provided they stay afloat and a port can safely load and unload them.

Even for such a simple process as moving industrial goods from A to B by ship, there are several roles to understand. Many companies act across multiple roles. Let’s look in more detail.

Ship Owners

I’d hope that the name is self-explanatory. A ship owner owns the vessel carrying the cargo. Some of the richest people of the 20th century were ship owners. Think of Aristotle Onassis: married to Jacqueline Kennedy (JFK’s widow), owner of the Monte Carlo Casino, founder of Olympic Airways and billionaire owner of more than 70 vessels. Some owners specialise in certain vessel types, others operate a mixed fleet.

Source: Shutterstock

Owners’ businesses are (unsurprisingly) asset-heavy, capital-intensive and they need their vessels to operate at as high a capacity as possible to generate acceptable returns. Ship owners therefore often enter into agreements with operators to use the vessels efficiently on their behalf.

Ship owners also have an inherent long freight position: they own the vessel and are sellers of freight. Vessels are valued in USD per day every single day and the vessel owner wants to maximise the amount of time spent commanding a fee for moving cargo. They need to manage this long freight position through a combination of charters for their vessels, physical contracts of affreightment and forward freight agreements.

Operators

Operators are freight traders in the market. They often focus their attention on a particular sector and/or geographic region and so develop expertise in particular cargoes and routes (e.g. Pacific Basin Iron Ore, Atlantic Basin Panamax).

Operators tend not to own the actual ships and the business is highly competitive, leading to low margins. Operators therefore rely on offering seamless customer service, strong vessel optimisation and require a high-quality flow of market information from brokers and analysts. They will also seek to mitigate price volatility in freight markets and fuel oil markets through use of derivatives such as oil product futures and forward freight agreements.

Charterers

Dry bulk charterers possess a cargo that needs to be moved. They are typically more focussed on the commodity being moved rather than the underlying freight market that ships it.

Charterers are inherently short freight and it is a cost to them, so their aim is to find and fix freight as cheaply as possible. In this respect, they hold an opposing freight position with the ship owners.

Charterers will often manage their own internal freight desk to gather and analyse freight market information so that opportunities can be shared with commodity traders. Czarnikow is frequently a drybulk vessel charterer and we have our own freight team who can fix vessels for our cargoes. We also have a large operations team to ensure that these movements happen as seamlessly as possible on behalf of our customers.

Charterers often have long-term relationships with a handful of suitable owners and operators they believe offer the best expertise, rates, flexibility and customer service.

Charterers will seek to mitigate their short freight positions through forward freight agreements.

Trading Houses

While trading houses are most frequently vessel charterers, they can also be vessel owners, operators or act in a combination of roles.

Trading houses aim to manage supply chains as effectively as possible through physical commodity trading, price risk management, commodity storage, multi-modal logistics and competitive financing. As part of this they often charter vessels to carry their own or third-party cargo. But they can also charter or purchase vessels to be long freight or to enable offshore storage of commodities. This most famously happened in 2008 and 2020 when crude oil was stored in tankers as prices collapsed.

Brokers

Brokers are intermediaries who help match and arrange freight contract/agreements between owners/operators and charterers. Once the charterer has found a suitable vessel and fixed it through the broker, the broker draws up the freight contract between the parties. While all agreements are confidential, freight brokers try to report fixing rates as best they can, meaning the freight market is often driven by gossip, just like any other market.

Shipping Agency/Port Agency

Agencies are designated companies who protects the interests of their customers at ports worldwide. Customers can be vessel owners, operators or charterers.

Source: Shutterstock

Shipping agents handle day-to-day operations surrounding the handling of cargo in ports, such as ensuring a berth for an incoming ship, arranging marine pilots, handling customs and harbour documentation, arranging vessel supplies and repairs, managing crew transfers, contacting shippers and the receivers of the goods and arranging matters with insurance companies in the event of a claim.

They also provide the shipping company with updates and reports on activities at the destination port so that shipping companies have real-time information available to them while goods are in transit.

Inspection Agencies

Inspectors assess the cargo before and after shipment to ensure that it has been moved correctly in accordance with the associated freight contracts. Agents can be appointed by cargo buyer or seller and monitor, inspect, test and approve goods at port or on vessels to ensure they meet quality standards, technical specifications and contractual requirements. They frequently check the quality, quantity and loading of drybulk goods through documentation review, visual inspection, sample measurement and weighing.

Czapp Explains – Freight series: Types of Freight