Freight Course Overview

Welcome to the third part of Czapp’s course on freight.

In the first episode we looked at the different ways that cargo can be moved through supply chains around the world.

In the second, we looked at the different participants in the drybulk freight market.

- Types of Freight

- Drybulk Ocean Freight: Who Does What?

- Drybulk Vessels, Cargoes and Routes

- Drybulk Freight Contracts

- Freight Costs and Price Risk Management

- Container Freight

Now we will move from the people to the ships themselves.

As a brief reminder, bulk freight means that the cargo is carried loose in a vessel’s hold. This method of transport is suitable for dry goods which are to be used industrially.

While it’s possible to move drybulk cargoes by rail, road or barge, ocean freight accounts for 99% of this market in terms of tonnage moved per year and so this is where we will concentrate our attention.

Drybulk Ships

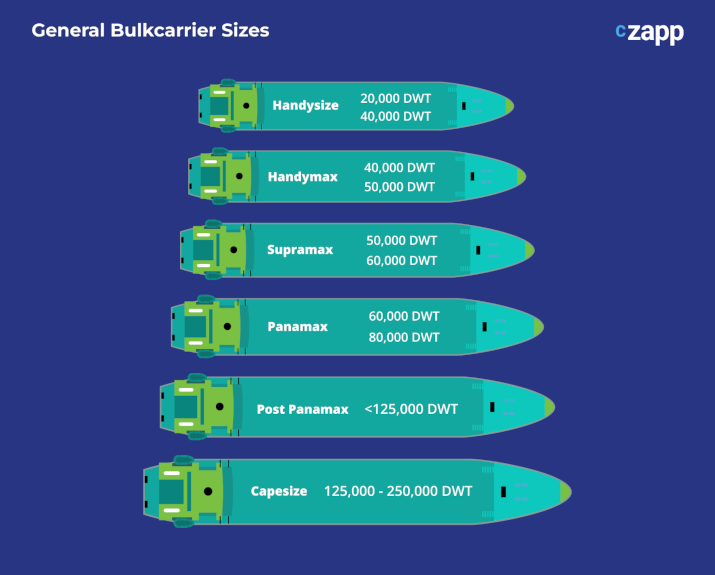

One of the most common ways to categorise drybulk vessels is by size. This can be measured by deadweight tonnage (DWT), which is a measure of how much a ship can safely carry. It’s therefore the total mass of the cargo, fuel, ballast, crew and provisions. Let’s look at these ships from smallest to largest.

Handysize

Any drybulk vessel under 40,000 DWT.

These ships tend to have a draft of no more than 10m, are typically 100-175m in length and have 5 holds/hatches.

Source: Shutterstock

These vessels also frequently possess their own “gear” (cranes and grabs so that the ship can load and unload cargo itself) and so don’t require extensive port infrastructure. They can therefore call at most of the world’s ports and can navigate the Panama and Suez canals. However, their small size means they don’t benefit from economies of scale that the larger classes of vessel do. They therefore tend to be used more for shorter voyages.

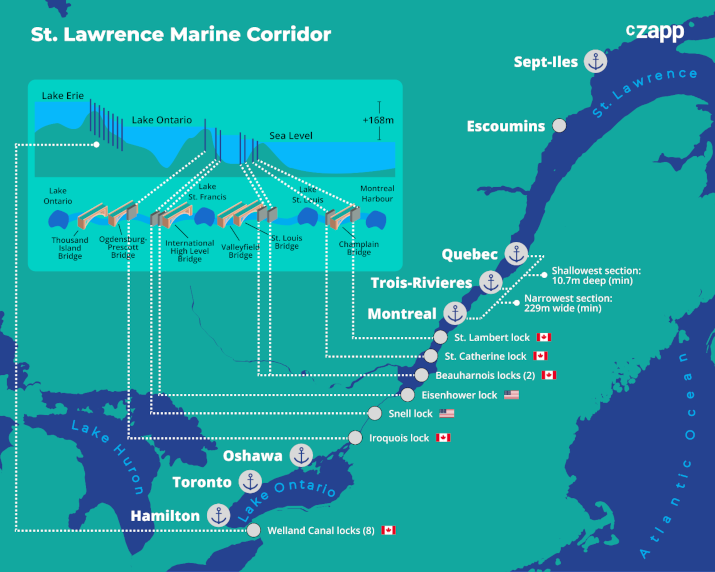

A special sub-class in this category is the Seawaymax, which are vessels that can use the St Lawrence Seaway. These vessels cannot be longer than 225m or wider than 23.8m. They also cannot have a draft more than 8.08m or a height above the waterline of 35.5m. Practically, these dimensions limit these vessels to a maximum of 28,000 DWT.

Handymax/Supramax

Any drybulk vessel between 40,000 DWT and 60,000 DWT.

These vessels are the larger cousins of the handysizes and are effectively the same except that they carry more cargo and are longer (up to 200m) with a deeper draft (up to 12m). This means they have better economies of scale but are unable to call at smaller ports or safely navigate the St Lawrence Seaway. They can still transit the Panama and Suez canals.

Panamax

The largest vessel that can transit the Panama Canal.

Source: Shutterstock

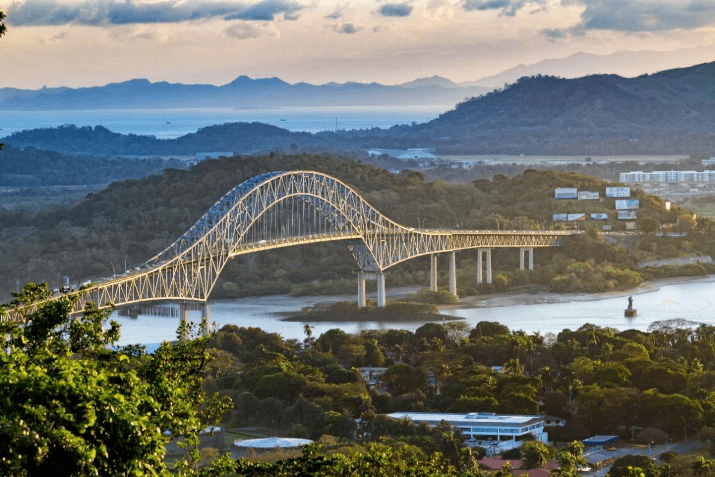

For almost 100 years, their dimensions were fixed by the size of the Atlantic and Pacific locks at 294m length, 32.2m width/beam and 12m draft, with a height limit of 57.9m in order to pass under the Bridge of the Americas.

Source: Shutterstock

In practical terms this meant that vessels of 80,000 DWT could transit empty, but were limited to 52,500 DWT laden.

In 2016 a third set of locks opened, allowing larger ships to pass through the canal. This has led to a sub-category called Post Panamax or Neopanamax. These vessels can be up to 366m in length, 51m beam with an 18m draft. The height limit remains unchanged. Post Panamax vessels can therefore be up to 120,000 DWT.

Source: Shutterstock

Panamax vessels usually do not have their own gear. This means they can only call at ports with suitable loading and unloading facilities. Panamax vessels usually have 7 holds/hatches.

Capesize

These vessels are too large to use either the Panama or Suez canals and so must traverse the Cape of Good Hope or Cape Horn to travel between oceans.

Source: Shutterstock

These vessels typically range between 100,000 to 200,000 DWT, are up to 300m long, 45m beam and have a draft of 18m. These dimensions are so large that most of the world’s ports are too small to handle these vessels, and so the cargo is often limited to iron ore or coal.

The ships typically have 9 holds/hatches and are gearless.

Goods Carried

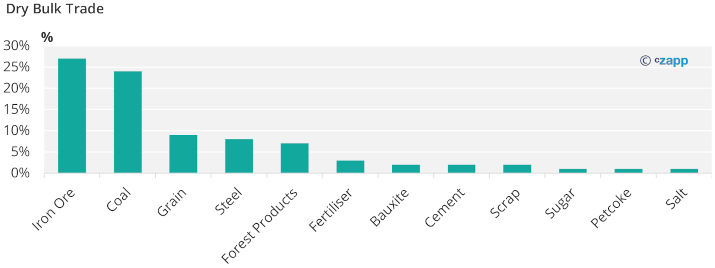

Drybulk trade is dominated by iron ore (c25% by mass), coal (c25% by mass) and grains (c10% by mass).

Together these three cargo classes comprise nearly 2/3 of global drybulk shipments. Other minor commodities account for the remainder and have much less influence over the freight market (eg Steel, wood products, fertiliser, cement, sugar).

Major Routes

Drybulk vessels typically steam at around 14 knots. Ships used to travel at more than 20 knots but travelling at this speed decreased fuel efficiency due to the increased water drag. Steaming at lower speeds can save up to 40% fuel.

Major routes include East Coast South America to East Asia, East Coast Americas to Western Europe & Mediterranean, Australia to East Asia, West Coast North America to East Asia.

Fuel

Bunker fuel is any type of fuel used aboard a vessel. A bunker is the tank on the ship or in the port which the fuel is stored in.

Marine bunker fuel tends to be heavier fractions from the distillation of crude oil; its price is therefore related to the price of crude oil.

Marine Diesel Oil is typically a lighter fraction and is used to generate power abord the vessel.

Intermediate Fuel Oil, Heavy Fuel Oil and Marine Fuel Oil are heavier fractions and used mainly to power the ship’s engines at sea. They can be viscous at room temperature so often need to be heated before they can be used. Heavy marine oils can also contain a high proportion of pollutants, notably sulphur, leading to high sulphur dioxide emissions.

In recent years the industry has attempted to reduce sulphur emissions from the global shipping fleet. This can be done either by installing scrubbers in ship exhaust systems or by using lower sulphur fuels. Ships can switch from high-sulphur fuel oil (HSFO) to marine gas oil (MGO). This is the easiest and quickest solution, but MGO is approximately 50% more expensive than HSFO.

IMO (International Maritime Organization) regulations to reduce sulphur oxides emissions from ships first came into force in 2005, under Annex VI of the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (known as the MARPOL Convention). Since then, the limits on sulphur oxides have been progressively tightened. Marine fuels used to be around 3% sulphur but in recent years low sulphur fuels (<1% sulphur) have become widely available. From 1 January 2020, the limit for sulphur in fuel oil used on board ships operating outside designated emission control areas was reduced to 0.50% m/m (mass by mass).

Bunkers typically comprise around 20-35% of the total freight cost and are often hedged to mitigate price risk. Bunkers are priced from three main trading hubs; Singapore, Rotterdam, and Houston as they give a representative price for key trading routes.

Czapp Explains – Freight series: Types of Freight