Insight Focus

All animals are not built equal. There are major differences in nutrition requirements among different categories of animals. This week, we look at ruminant animals, such as cattle, sheep and goats.

Ruminants, such as cattle, sheep and goats have sophisticated digestive systems enabling them to access energy and nutrients from their feed. As mentioned in our last article, ruminants are less tolerant of high levels of ‘concentrate’ feeds than monogastric livestock. As a result, ruminant diets are generally made up of ‘bulky’ feeds with smaller amounts of concentrate feeds. The exception is the finishing of livestock for meat production.

The principles of ruminant digestion use mechanical and chemical breakdown of feed, allowing efficient absorption of water, energy, protein, vitamins and minerals.

The Process

Food enters the mouth, where the mechanics begin as it is chewed. This encourages increased saliva production to kickstart the chemical breakdown process.

The next stage is passing through the oesophagus, which is bi-directional. This will be useful later in the process.

The Stomachs – All Four of Them!

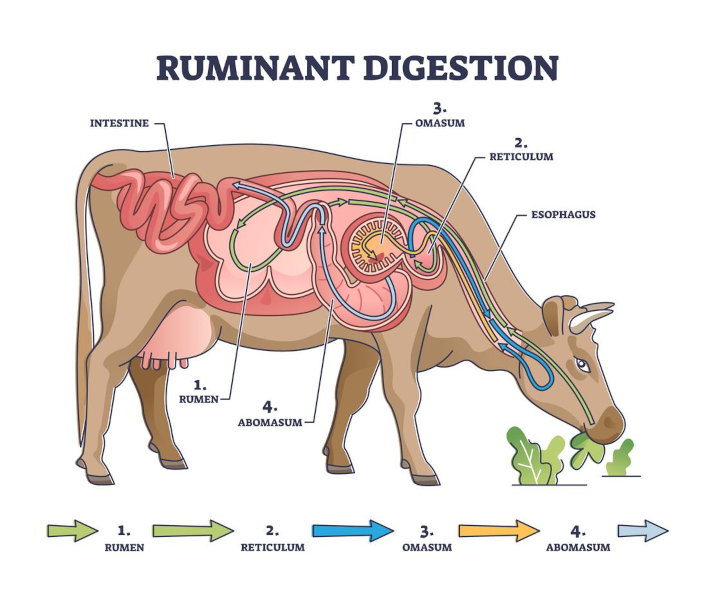

The most fascinating part of a ruminant’s food breakdown takes place in the four chambers or stomachs:

1. The Rumen

2. The Reticulum

3. The Omasum

4. The Abomasum

1. The Rumen

As in the diagram above, the rumen is the first chambered stomach. In a cow this can hold the equivalent of 100-150 litres of liquid and is the largest of the four chambers, holding up to 60% of the total volume.

There are huge numbers of microbes at work here, which with the help of saliva and involuntary stomach contractions, aid the breakdown of cell walls, facilitating the accessibility of energy and nutrients from feed.

These microbes like stable environments to do their work, so sudden or frequent dietary changes will reduce their efficiency.

Fibre in the diet helps to slow the passage of food through the rumen, which is essential for efficient digestion, although there is plenty of water to keep things flowing and not stagnating for too long.

Food can remain in the rumen for 48 hours or more, enabling the microbes to break down material. The coarser material will pass back through the bi-directional oesophagus to the mouth where it will be chewed further, often referred to as ‘chewing the cud’. Ruminants, whether sheep, goats or cattle spend many hours every day chewing the cud to aid digestion.

There is a small fold of tissue between the rumen and the next chamber, the reticulum, which is also bi-directional, so sometimes referred to as the reticulo-rumen. This allows material to pass back to the rumen if further breakdown is required at this stage.

2. The Reticulum

A small pouch lined with a honeycomb type tissue, sometimes referred to as the honeycomb.

Its primary function is transitional, collecting smaller material to pass on through, while larger material can be passed back to the rumen and mouth for further breakdown, chewing the cud.

3. The Omasum

This third chamber is ball shaped, lined with leaves of tissue, while its size is animal dependent.

Its primary objective is to aid water reabsorption, together with some nutrient absorption. It is the part of an animal often eaten as tripe.

A ruminant’s first three stomachs have large surface areas to encourage nutrient and energy absorption, while the microbes are busy breaking down material cell walls.

At the time of leaving the omasum, feed material is quite small.

4. The Abomasum

Similar in many respects to human and monogastric stomachs, it contains high acidity gastric juices and enzymes, further processing remaining food particles.

The Intestines

The destination for major nutrient absorption, the small intestine uses enzymes from the pancreas and gall bladder to further process food particles. A huge number of villi form the surface wall, enable nutrients to pass through into the blood and lymph system.

The final chapter in the digestive process, the large intestine, has its own microbes, drawing out any remaining nutrients. It also plays a vital role in the reabsorption of water used in the digestion process, prior to material being passed on to the rectum for excretion.

In Simple Terms…

Our ruminant livestock, such as cattle, goats and sheep possess a fascinating and complex digestive system.

The mechanical and chemical processes of allowing food to move both forward and backwards and chewing the cud demonstrate an extraordinarily efficient feed absorption method. This results in the extraction of every unit of nutrient and energy possible from sizeable bulky feeds.