El Niño or La Niña?

El Niño and La Niña are part of the same atmospheric phenomenon that occurs in the Equatorial Pacific Ocean. The main indicator of this phenomenon is the temperature fluctuation (warming or cooling) of the Pacific Ocean waters.

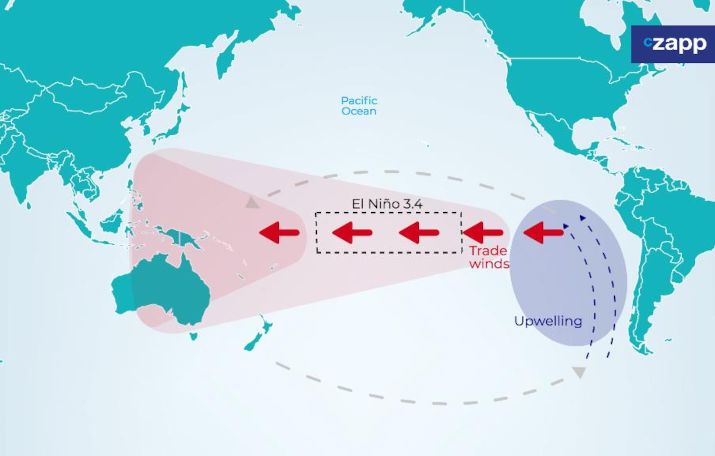

When the sea surface temperature (SST) of the El Niño 3.4 region (located more or less in the middle of the Pacific Ocean) is above 0.5ºC of the average for three months, we have an El Niño. And when the temperature in the same region is 0.5ºC below normal for three months, we have La Niña

In short…

- If SST in El Niño 3.4 region is 0.5ºC above the average = El Niño

- If SST in El Niño 3.4 region is 0.5ºC below the average = La Niña

Wind movement under normal conditions

Under normal conditions, the trade winds (mass of warm, moist air) in the Pacific Ocean carry the warm water from the American coast towards the west until it reaches Southeast Asia.

When it reaches Southeast Asia, this hot water favours the formation of rain in the region.

Normal Conditions

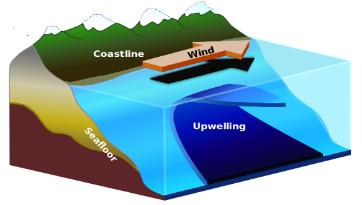

Upwelling phenomenon

At the same time that the warm waters are blown westwards by the winds, the deep cold waters emerge off the American coast, causing the phenomenon called upwelling.

How does El Niño occur?

El Niño happens when this air mass loses intensity. Less hot water is displaced to the west with lower wind strength, and less cold water from the ocean floor comes to the surface. As a result, the average surface temperature of the Equatorial Pacific Ocean is warmer compared to normal conditions.

Movements in a year of El Niño

How does La Niña occur?

The La Niña phenomenon is the opposite of El Niño. It occurs when the trade winds strengthen, intensifying the transport of water towards Southeast Asia.

Therefore, there is an increase of cold water on the American coast and the surface temperature of the Pacific Ocean becomes cooler than the average.

Movements in a year of La Niña

El Niño and La Niña impact global temperature

Analysing the occurrence of these phenomena leads us to believe that El Niño/La Niña happens in a relatively cyclical way, on average every 2 to 8 years.

It is likely this phenomenon has been happening for thousands of years without human interference. But recent studies indicate that climate change appears to be increasing its frequency.

During El Niño years we have warmer temperatures, and in La Niña years we have the opposite, cooler temperatures.

In late 2014, the strongest El Niño on record began, which stretched into early 2016. As a result, 2015 broke the record for the hottest year in history (in red in the chart above).

Impacts of El Niño or La Niña in Brazil

Brazil is only bathed by the Atlantic Ocean, but it is still influenced by what happens in the Pacific Ocean. During El Niño or La Niña events, we experience changes in rainfall patterns and temperatures across the country (in detail below).

Due to excessive rainfall or prolonged drought, agriculture and the agricultural market are directly affected. The phenomena can happen at any time of the year, when the temperature of the El Niño 3.4 region is above/below (El Niño/La Niña respectively), but we see it more intensely and more noticeably during the summer (Dec to Feb) and winter (Jun to Aug), of southern atmosphere.

El Niño/La Niña has well-defined impacts on rainfall patterns in South and North Brazil. However, the Southeast and Midwest are transition zones, it is in between two regions directly affected by the phenomenon in different ways. Therefore, it is difficult to confirm the relationship and there is no consensus on the impacts in terms of rainfall in these areas – the effects are measured case by case and depend on the intensity of the phenomenon.

El Niño

El Niño increases the average temperatures across the country, especially in the South and Southeast.

In the South, there is also an intensification of rainfall, which can be beneficial for crop development. However, if El Niño occurs during the harvest period, the higher precipitation can disrupt field operations.

In the North and Northeast regions, there is a decrease in rainfall which can result in droughts and increased risk of fire. In the Southeast and Midwest, there is no clear effect of rainfall, therefore, the result of the effect must be analyzed case by case. For example, the last strong El Niño recorded between March 2015 and June 2016, the state of Minas Gerais (located in the CS) benefited from the moderate increase in rainfall in some areas. It helped to minimize the effects of the water deficit that occurred in the previous season (2014/15). During the same period, the state of Mato Grosso do Sul (Midwest) suffered from excessive rainfall, mainly in July/2015, which directly impacted the sucrose concentration (ATR) and also reduced the number of working days.

La Niña

The La Niña phenomenon, as mentioned before, presents an inverse behaviour of the El Niño.

In other words, the South part of the country tends to be colder and with less precipitation than normal. For North and Northeast regions above-average precipitation is observed.

In Southeast, the La Niña phenomenon usually causes a moderate drop in temperature in the region. However, it does not present a characteristic change in the pattern of precipitation, depending on the intensity of the phenomenon. However, taking as a reference the latest La Niña events that took place between 2010-2012 and the most recent in 2020, the drought was felt in the region, impacting the agricultural productivity of several crops – including sugarcane.

In Midwest, we have mild effects both in temperature and rain, but with a tendency to drought, as seen in 2010 and 2012.

In an extremely simplified way, the phenomenon of El Niño and La Niña results in the following effects in the Brazilian territory:

El Niño

North: Decreased precipitation and droughts, increased risk of forest fires.

North East: Droughts of different intensifies in the region.

Midwest: There are no pronounced effects in rains and in temperature. But there is a trend of increased rainfall in southern Minas Gerais.

Southeast: There is no characteristic pattern of precipitation change but there is a moderate increase in average temperatures.

South: Precipitation above average and increase in average temperature.

La Niña

North: Increased intensity of the rainy season, causing floods of rivers in some regions.

North East: Above average rainfall in the region.

Midwest: There are no pronounced effects in rainfall and temperature, but there is a tendency for drought.

Southeast: There is no characteristic pattern for precipitation, but a moderate decrease may occur in average temperatures.

South: Drought in the region, especially during winter.

This Czapp Explainer was Published on the 15th November 2021.

For information on our consultancy offering and other projects, please contact SGeldart@czarnikow.com.