Welcome to the fourth instalment of Czapp’s course on futures market spreads. In previous explainers we looked at what a spread is, why they are relevant to market participants and analysts, and what the key drivers of futures market spreads are.

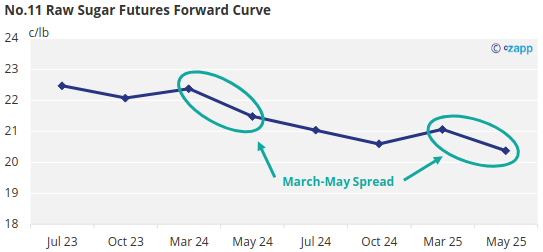

In this explainer we will cover the specific drivers of the No.11 raw sugar futures March-May spread.

In upcoming explainers we will look what factors drive the remaining No.11 raw sugar futures spreads.

No.11 Raw Sugar Futures Contract

There are four No.11 raw sugar futures contracts traded in a calendar year, the March, May, July, and October contracts. This means there are four spread pairs between neighbouring contracts, the October-March (V/H), March-May (H/K), May-July (K/N), and July-October (N/V). For more information on the No.11 raw sugar futures contract, please see our explainer.

March-May Spread Overview

Given the contract months involved, the March-May (H/K) spread is relevant to supply and demand in the raw sugar market from the end of Q1 to the end Q2.

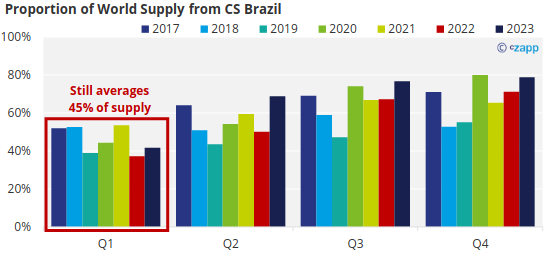

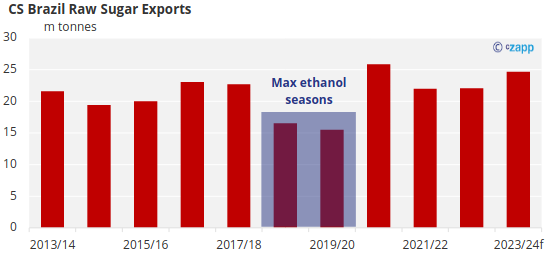

Despite the major northern hemisphere producers usually being at the height of their export programmes during Q1 (India, Thailand, and producers from Central America), the March-May spread still tends to be dominated by Centre-South (CS) Brazil.

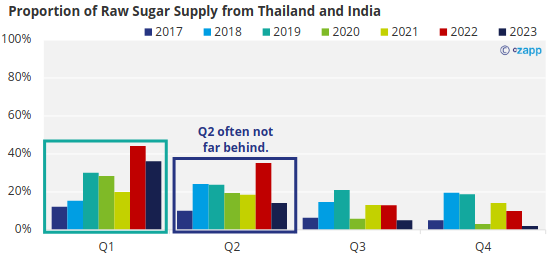

Thailand and India are normally the 2nd and 3rd largest raw sugar exporters and in Q1 on average account for around 25% of total raw sugar supply, the highest it usually reaches in a year.

However, their ability to export in Q2 is generally not too far behind. Over the previous 6 seasons, India and Thailand account for on average 20% of global raw sugar supply.

With supply from each then somewhat split evenly between the March and May expiries, neither contract is weighed upon particularly more than the other.

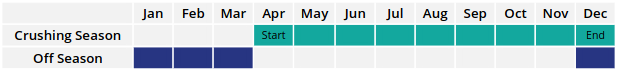

However, Q1 and early Q2 (the period covering the March-May spread) spans the off crop of the CS Brazil season when sugar stocks from Brazil are at their low point.

Only when crushing starts for the new season in around April do stocks in the centre-south begin to pick back up again.

This means that supply from the world’s largest raw sugar exporter is lopsided over this period, comparatively plenty more against the May expiry than the March.

For context, even when stocks are at their lowest, CS Brazil still comfortably out supplies Thailand and India combined, supplying over 45% of the world’s raw sugar in Q1.

By Q2 this reaches over 55%, and as a result the March-May spread tends to trade at a premium, given supply tends to be relatively more abundant in May than in March.

Who has Sugar to be Delivered into the Expiry?

Sugar priced against the March raw futures contract generally aims to be delivered in Q1-Q2. For sugar specifically delivered through the exchange the delivery window is precisely 75 days long, from the 1st of March to around the 15th of May. To understand the distinction here is an explainer on what futures markets are used for.

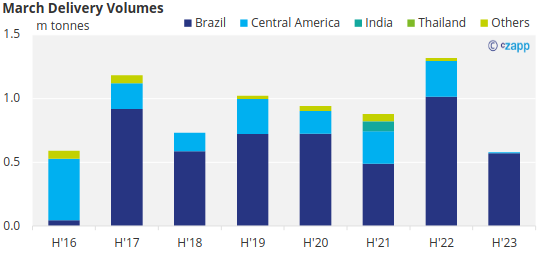

As mentioned above, any old crop Brazilian raw sugar will be delivered into the March contract to clear room for the new season sugar.

Central American producers will also deliver surplus sugar into the March contract if it trades above their cost of carry.

Other key producers India and Thailand will normally be in the middle of their export programs by this point in the year, however it is rare that they will deliver into the March expiry unless the March contract trades at a high premium.

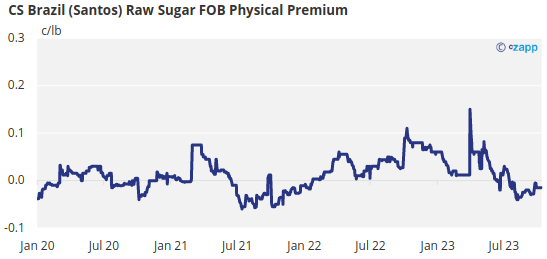

Since CS Brazil is the largest exporter, and during peak season will also hold a large volume of stock, sugar here often trades at a discount to the futures.

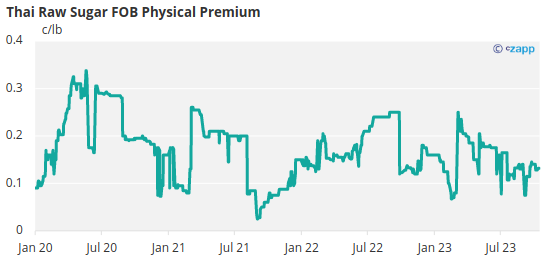

Whereas for sellers in Thailand and India, their physical premium is often much higher since Asia is a sugar deficit reason, meaning that buyers are prepared to pay above the world market price to acquire supply.

This often means that the March-May spread isn’t strong enough to encourage Thai and Indian sellers to deliver into the March expiry, instead they normally prefer to sell against May contract and capture the large physical premium instead.

This all said, the March contract expiry is often much less ‘clean’ than the October expiry, with receivers risking taking sugar from a number of origins.

Having less certainty over the origin can reduce the appetite to receive sugar from the tape, meaning delivery volumes can be smaller than other contract expiries.

What Should be Paid Attention to?

As with every spread, understanding what stage the CS Brazil crop is at is important.

For March-May this means being aware of how much old crop sugar there is likely to be sold against the March contract, and understanding when crushing for the new season will begin.

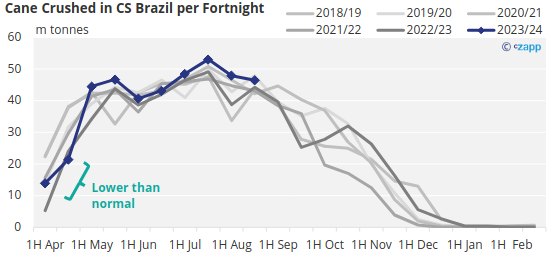

The new season normally starts around the start of April, though if there is lots of stoodover (uncrushed) cane left from the end of the previous season this can pull forward slightly the start date, as can drier than normal weather at the end of March.

Likewise, if the sugar cane hasn’t been maturing well, or if there is strong rainfall around the start of April this can push the start date back.

For example, early season rains in 2023/24 meant access to the fields were limited during the first few weeks of the season, as such it saw one of the slowest starts to the season in recent years despite intentions to start as early as possible.

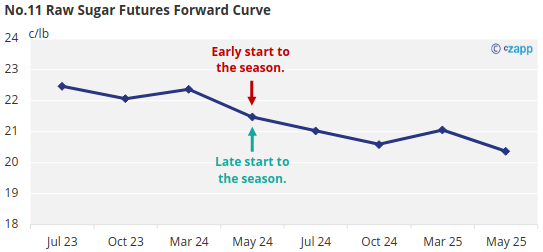

These factors then influence how much sugar is available for export against the May contract, an earlier start can provide downwards pressure on the May contract, a late start, the opposite.

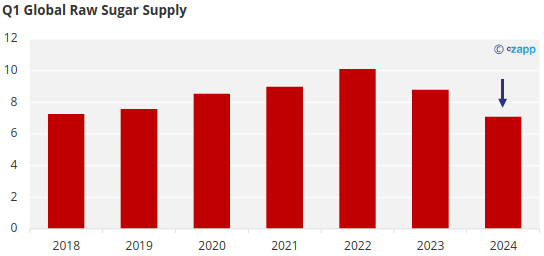

Whilst the high point of supply from India and Thai in Q1 is not enough to prevent the March-May spread from trading at a premium, an absence of sugar from these producers is often felt strongly.

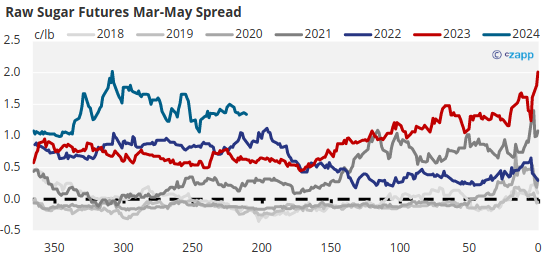

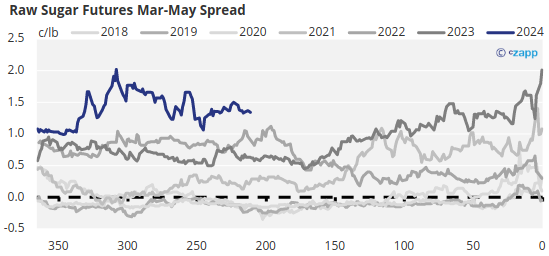

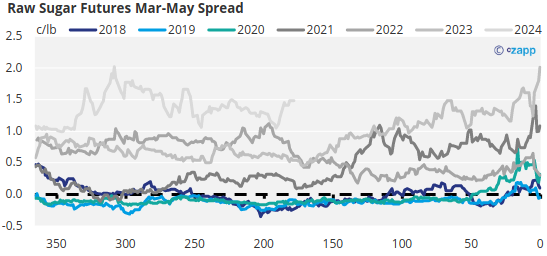

The 2024 March-May spread (at the time of writing) has been at the highest premium of any March-May spread since at least 2018.

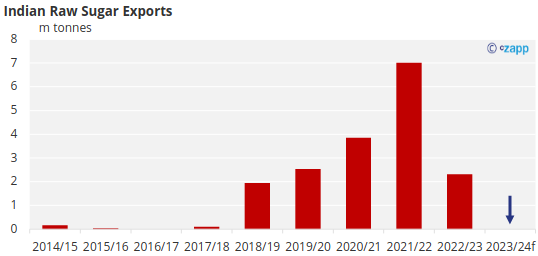

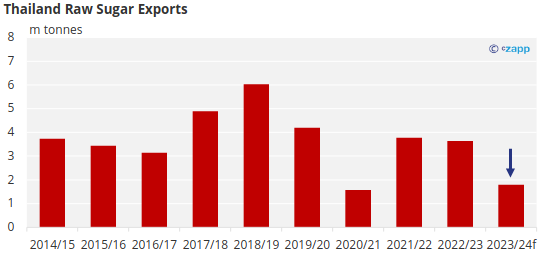

Throughout 2023 it had been understood that exports from India and Thailand would not be stellar, at the time of writing we expect India to not export any sugar, this would be the first time since 2016/17.

Equally Thailand is set to suffer the worst crop in almost two decades.

This puts a particularly large hole in Q1 supply, almost 2m tonnes less than 2023, and 3m tonnes less than in 2022.

This coincides with the prospect of the largest sugar crop ever from CS Brazil in 2024/25 (at the time of writing) which would begin against the May 2024 contract.

The expectation by those in the market of an unusually large differential between supply against the March contract and the May contract has driven the March-May spread particularly high, a particularly long time before it expires.

Exceptions to the Rule

The March-May spread tends to fairly consistently trade at a premium, even in years that it does trade at a discount (2018-2020) they still were very close to flat, barely trading at more than a 15-point discount.

For 2018 and 2019, these years cover a period where ethanol better compared to sugar for CS Brazil mills. With sugar production sacrificed to boost ethanol production there was a smaller difference between supply in the off crop during Q1 and supply in the early season in Q2.

With less of a differential between sugar available against the March vs the May contracts the spread became reflective of this.