Welcome to the first instalment of Czapp’s course on futures market spreads.

In this explainer we will look at what a spread is and why they are relevant to market participants and analysts.

In the upcoming explainers we will look at the types of factors that drive changes to the value of spreads, and what factors in particular drive the No.11 raw sugar futures spreads.

What is a Spread?

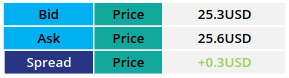

In finance a spread in its most basic definition refers to the difference between two indicators. One simple example is the spread between bid and ask prices of a commodity, however, a spread can be between any two prices, rates, yields etc.

A spread therefore allows the price/rate/yield of two indicators to be rationalised into one unit, which in many instances can be traded.

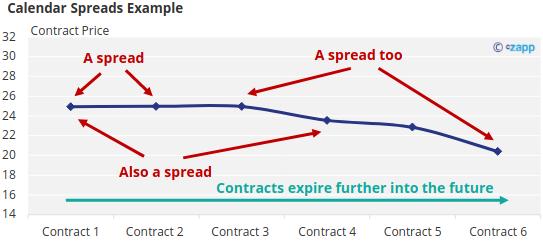

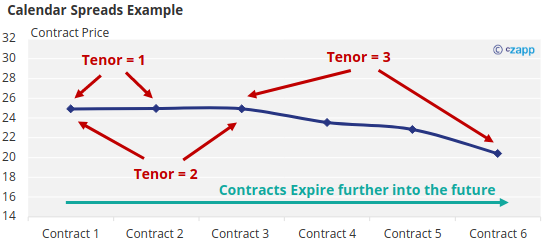

Within the context of futures markets, spreads generally refer to the calendar spread between two futures contracts, in other words, showing how two futures contracts with different delivery dates relate to one another. The most commonly looked at spreads are those between neighbouring contracts (for example the closest contract to expiry paired with the next nearest to expire).

Now note the amount of time there is between the expiries of the two contracts in the spread, the number of gaps between one contract in the spread and all other contracts in between the other contract is counted. This is called the ‘tenor’.

For example, the spread between neighbouring contracts has a tenor of 1.

How to Calculate a Calendar Spread

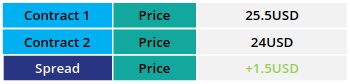

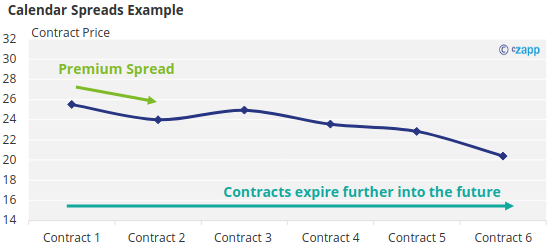

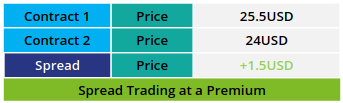

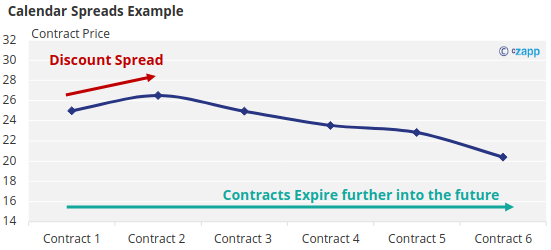

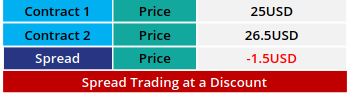

The value of a spread is constructed by taking two futures contracts and subtracting the price of the later-dated contract from the contract closer to its expiry.

If this is positive, then the spread is said to be trading at a ‘premium’ since the closer-dated contract is more expensive than the later-dated contract.

If the value of the spread is negative then it is trading at a ‘discount’.

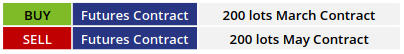

Futures market calendar spreads are tradeable in their own right, ‘buying’ a spread refers to buying the nearer to expire contract and selling the further to expiry contract simultaneously. ‘Selling’ a spread is the opposite.

Why are Spreads Important to Market Participants?

Futures contract spreads are important both for market participants to mitigate their risk and increase their flexibility, and for analysts looking to judge the supply and demand situation in the underlying commodity.

Greater Hedging Flexibility

To offer some background, futures markets are generally used to manage the price risk of buying and selling the underlying physical commodity.

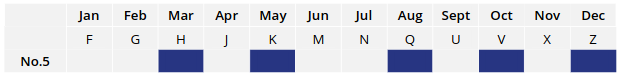

This in mind, the delivery of the physical commodity can be arranged for any time by the buyer and seller, yet futures contracts are tied to specific months of the year, in the case of refined sugar these are March, May, August, October and December.

This causes an obvious problem where the futures market and the physical market may not cleanly align, or if the timings of the delivery change, can leave the futures market hedge mismatched.

Let’s say you are a sugar producer (the process works just the same for a consumer as well).

It’s currently January and you have 10k tonnes of sugar to sell for delivery in March. You approach Cz to help facilitate the sale of your sugar.

Cz will look at the futures market to find the closest futures contract to the March shipment date, in this case the March futures contract.

Using this, Cz agrees a fixed price that works for you.

![]()

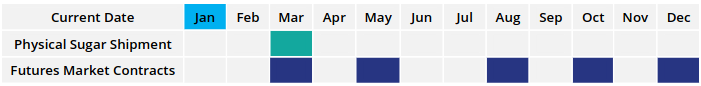

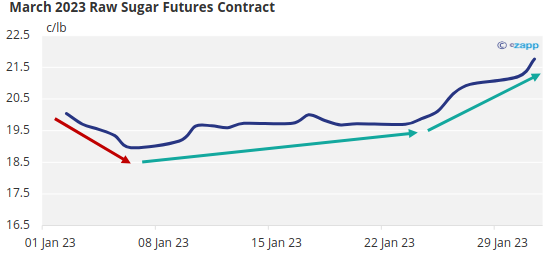

To mitigate the price risk Cz then immediately sells 200 lots (1 lot is 50.8 tonnes) of the March futures contract.

![]()

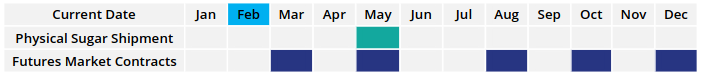

It is now February, a problem has occurred where the original March delivery date is no longer possible, you will now only be able to deliver your sugar in May instead.

This leaves Cz with 10k tonnes of sugar to be delivered in May, hedged against a March futures contract, a mismatch.

Cz will have to buy 200 lots of the March contract, then sell 200 lots of the May contract, thereby ‘rolling’ the hedge such that it is realigned with the new delivery date.

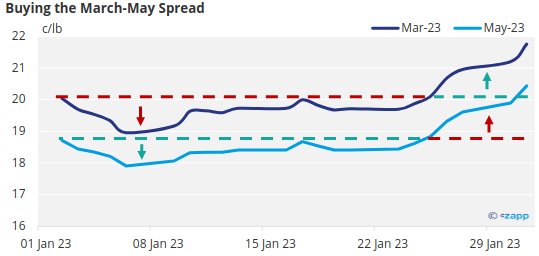

Since Cz has bought the nearer-dated contract and sold the later-dated contract, Cz has bought the March-May spread.

![]()

In another example, if the delivery date of the physical sugar lies between the expiries of two futures contracts, Cz can use whichever is the most cost effective to hedge the physical trade, and then buy or sell the relevant spreads in the future if the other relevant futures contract becomes more cost effective.

Therefore, buying and selling the spreads allow Cz to be more cost efficient and offer greater flexibility to provide price risk management to our clients.

Lower Volatility

Aside from the flexibility, using spreads is also beneficial for minimising volatility. If we look at a single contract over the space of a month, it can trade over quite a large range.

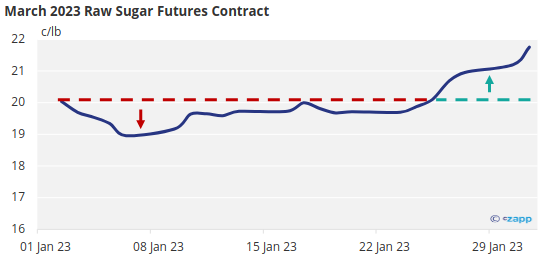

For example, the March 23 raw sugar futures contract traded in a range of 280 points (2.8c/lb) during the month of January 2023.

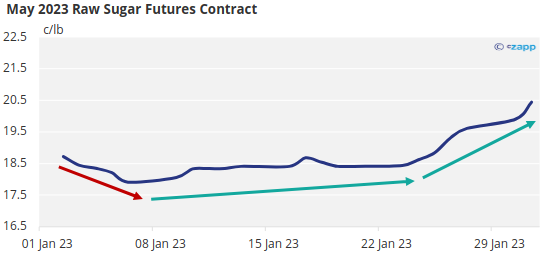

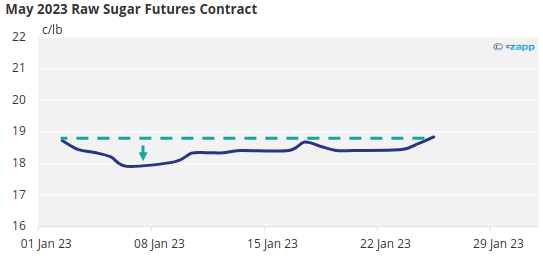

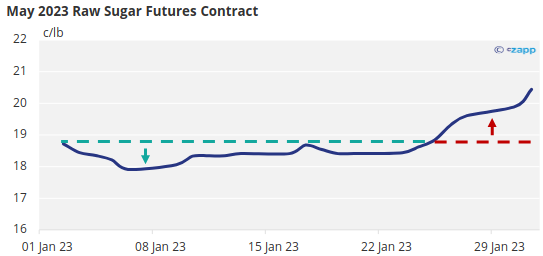

Whilst the May 23 contract (the proceeding raw sugar futures contract) traded in a range of over 250 points (2.5c/lb) over the same period, also a fairly large trading range.

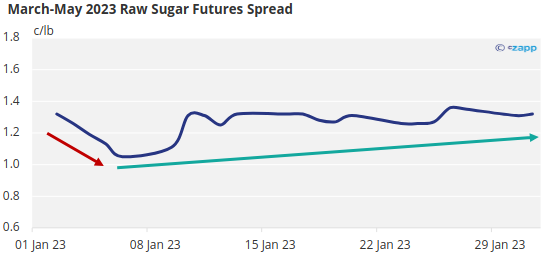

Yet since most contract pairs are generally somewhat correlated with each other the March-May 2023 spread traded in a range of only just over 30 points (0.3c/lb).

Whilst this is just one example the rule tends to hold true in general, the risk profile of a spread tends to be much lower than the outright contracts which it is based on.

Lower Margin Costs

This is important since futures contracts trade using margin, a form of borrowing that allows participants to control larger positions than would be possible without. Margin acts as collateral against the risk of the contract increasing or decreasing in value after a position has been taken out and must be held at a constant value.

This means that in the case of buying one lot (unit) of a futures contract, should the contract price subsequently fall, the value of the initial margin would no longer be sufficient, and it would have to be topped up.

Likewise, should the contract price rise, the value of the initial margin would be in excess, this excess would be paid back to the buyer.

The opposite is true for a short position in each case, this process is undertaken daily until the contract is closed out and is called variation margin.

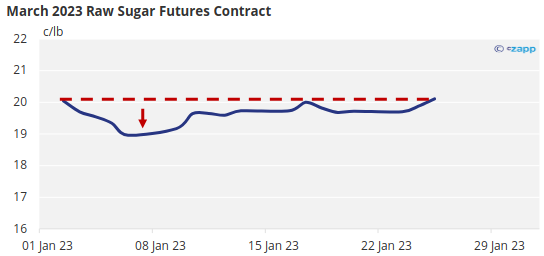

Using the previous example, say you purchase one lot of the March 23 raw sugar contract for 20c/lb on the 3rd of Jan.

Until the 25th of Jan the price had traded below the purchase price, the initial margin would at the time of purchase over this period would be less than is now necessary and would need to be topped up.

However, from the 26th of Jan the price traded back above the initial purchase price and increased further, reaching almost 22c/lb by the end of January. The amount held in margin would now have been more than amount required for these trading days and so the excess would be paid back to you.

The same but opposite would be true if you also sold one lot of the May 23 contract at the start of January since neighbouring contracts are generally somewhat correlated.

Excess margin until the 25th Jan that would be paid back to you.

Shortage of margin from the 26th of January until the end of the month that would need to be topped up.

Undertaking these two positions simultaneously (buy March 23, sell May 23) is the same as buying the March-May 23 spread. Shortage compared to the initial margin against one half of the spread should be broadly offset by excess compared to the initial margin from the other half of the spread.

Thus, compared to taking out an outright position, taking out a spread acts like a hedge due to the correlation between contracts, reducing the risk and therefore the variation margin for the market participant too.

Additionally, as we covered earlier, since spreads are much less volatile than the outright contracts that they’re based on, they command a much smaller initial margin as well.

Why are Spreads Important to Analysts?

Spreads are an important tool for analysts too.

For an analyst a calendar spread can offer insight into the expectations of future supply and demand, in other words, when supply of the underlying commodity becomes available and when consumers are looking to buy.

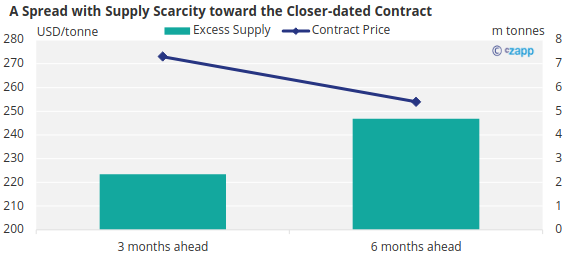

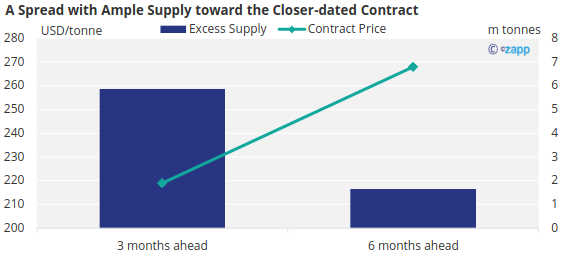

If a spread is trading at a premium (when the closer-dated contract is more expensive) this implies that there is a greater scarcity of the underlying commodity around when the closer-dated contract expires, relative to when the later-dated contract expires.

Likewise, if the spread trades at a discount it suggests the market is better supplied in the near term, becoming tighter closer to when the later-dated contract expires.

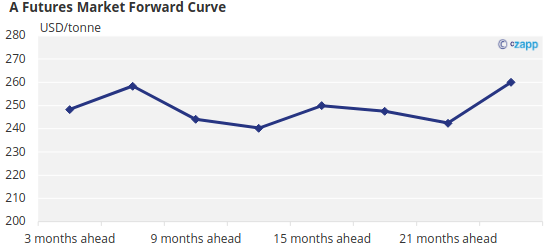

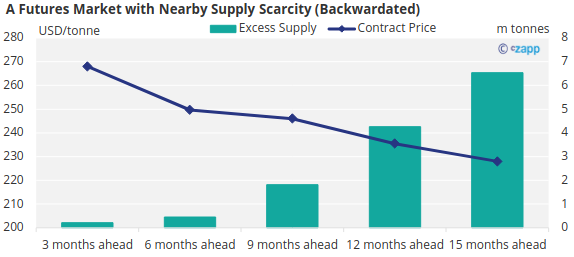

By chaining together the spread pairs for every futures contract currently tradeable a forward curve is created. A forward curve can offer insight into the relative scarcity or abundance of the underlying commodity on the world market over a longer period of time into the future.

If most of the spreads are trading at a premium, then the forward curve will appear downward sloping, this is called backwardation.

When a forward curve is ‘backwardated’ it suggests that there is a more serious scarcity of the underlying commodity in the shorter term, and the curve encourages buyers to defer buying further into the future, and sellers to advance their supply closer to the present to help resolve the nearby tightness in the market.

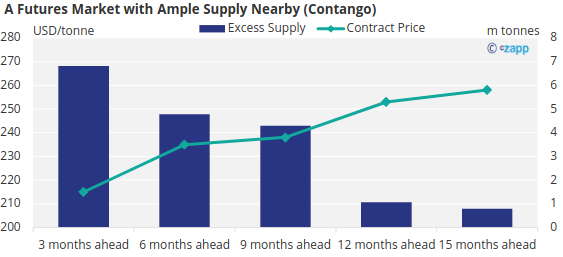

Instead, when most of the spreads are trading at a discount and the forward curve appears upward sloping then the market is said to be ‘in contango’.

In this case the forward curve indicates that scarcity will become apparent further into the future and encourages buyers to advance their demand closer to the present, and sellers hold on to their supply further into the future to help resolve the market tightness.

If you have any questions, please get in touch with us at Jack@czapp.com.