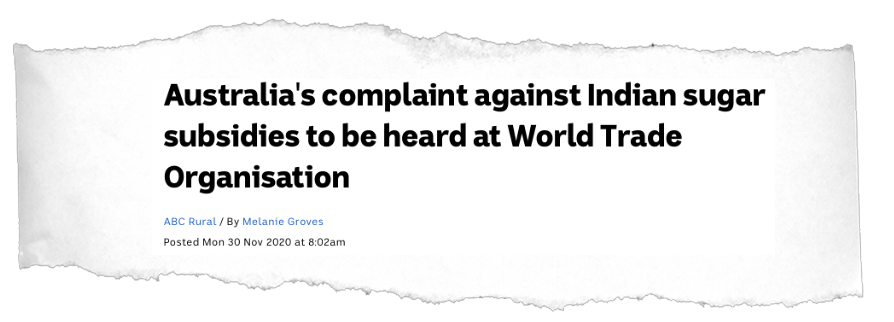

- The Indian government wants a 20% blend of ethanol in gasoline by 2025.

- This will save millions of tonnes of cardon dioxide emissions each year.

- This is being done because India overproduces sugar, thanks to the success of its cane scientists.

Dr Bakshi Ram leads the team of researchers at the Indian Council of Agricultural Research Sugarcane Breeding Institute (ICAR-SBI). They are indirectly responsible for launching India’s ethanol blending programme, which promises to save millions of tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions each year. This is because their cane breeding efforts have been so successful in the last decade that India is now a consistent overproducer of sugar.

The government’s answer to this is to divert some of this sucrose to ethanol production, copying Brazil’s pioneering approach. This is a generational change for India’s cane industry and for most sugar market watchers, most of whom are more accustomed to India being a swing sugar producer. Let’s begin by examining why India’s swing cycle no longer exists.

India’s Swing Cycle (RIP)

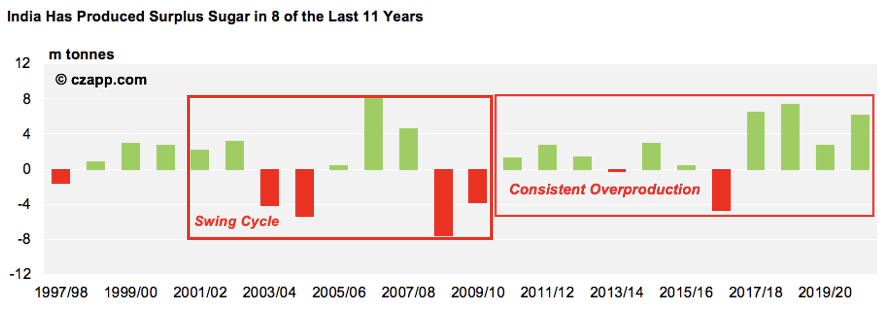

Mention the words “Swing Cycle” to anyone in the sugar market and chances are they’ll think you’re referring to India. But India hasn’t been a swing producer of sugar for more than a decade.

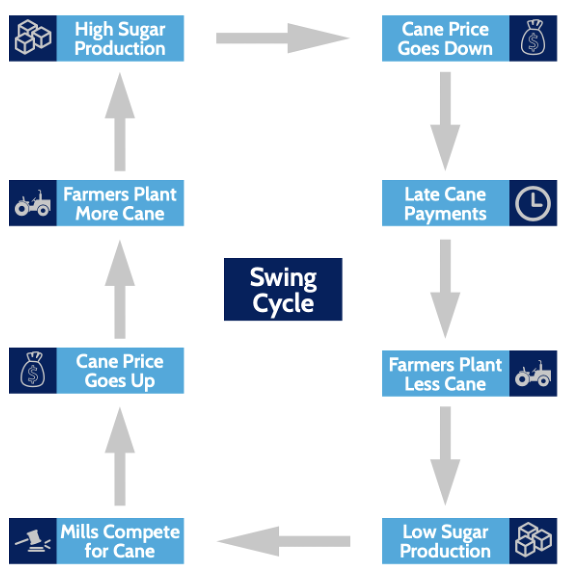

A decade ago, Indian sugar production was erratic as farmers responded to late cane payments or high cane prices.

India would swing between oversupply, which was exported to the world market, and undersupply, needing world market imports.

The ‘Swing Cycle’ was eventually broken in two ways.

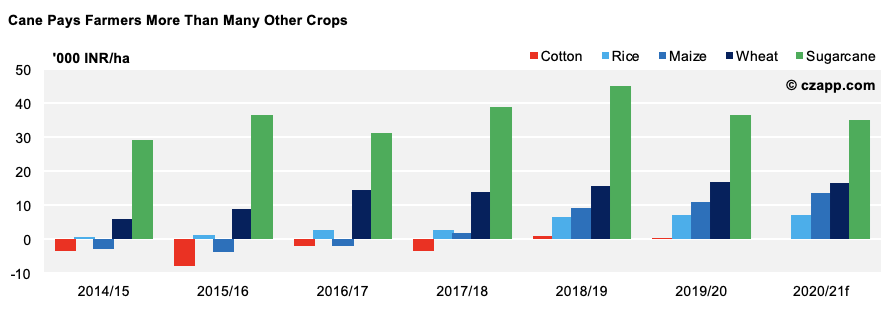

1) The cane price paid became so attractive that other crops couldn’t compete.

Farmers stopped planting other crops instead of cane because even a partial and late cane payment was better than the return any other crop could provide.

2) Thanks to Indian cane scientists at the Indian Council of Agricultural Research Sugarcane Breeding Institute (ICAR-SBI).

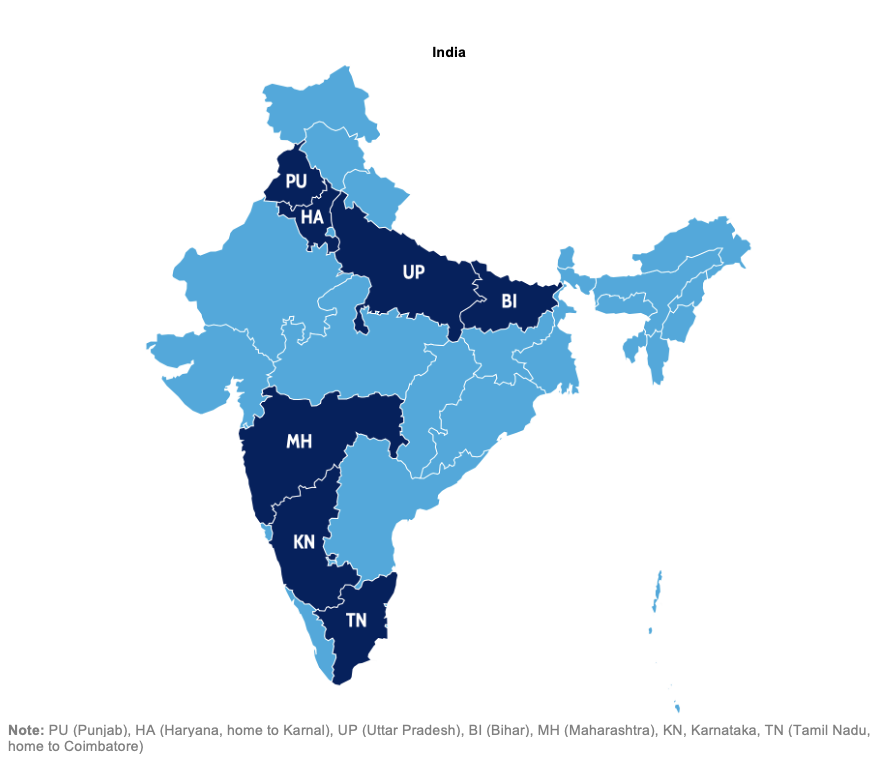

The institute is responsible for releasing new cane varieties and promoting better farming practices for these new varieties. We’re most interested in their recent work in North India.

A New Boom in Indian Sugar Production

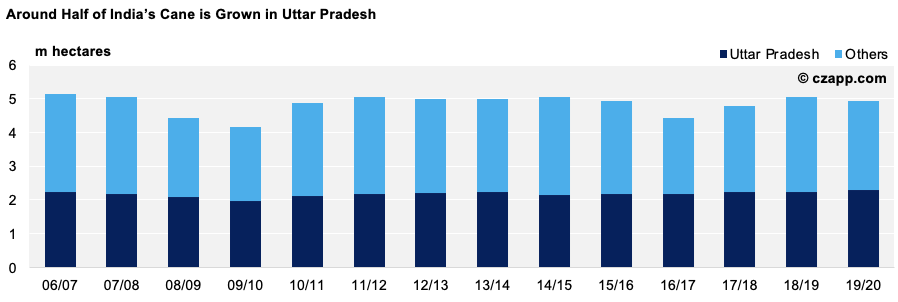

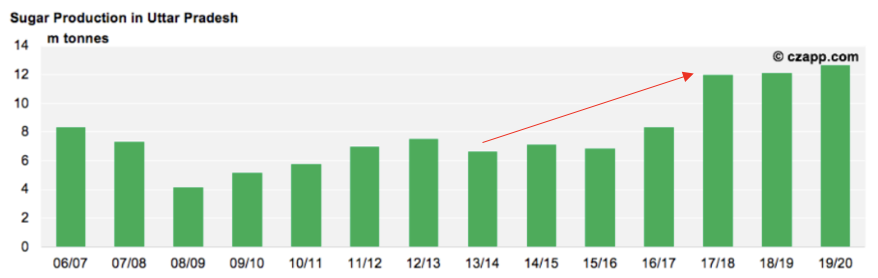

Around half of India’s sugar cane is grown in the north of the country, predominantly in the state of Uttar Pradesh (UP).

At the turn of the century, the dominant cane varieties grown in UP had been developed in the 1970s and 1980s and were relatively low yielding. In 2009, ICAR-SBI released four new varieties for testing in northern India.

Inter-state rivalry can be intense and ICAR-SBI is headquartered in Coimbatore, in the south of the country. Even though the new cane varieties were developed at Karnal in Haryana in the north, the ICAR-SBI still needed to encourage widespread adoption of the new varieties by northern Indian farmers and cane millers.

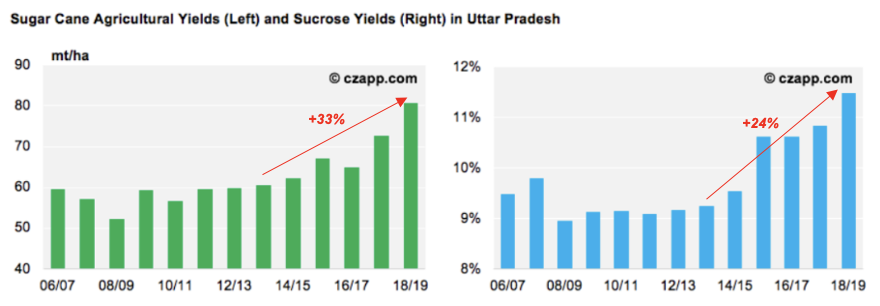

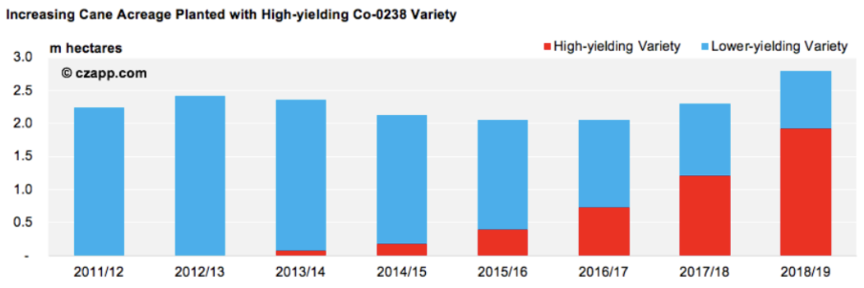

ICAR-SBI arranged large-scale trials in UP, Bihar, Haryana and Punjab. One of the varieties, Co-0238, emerged as the best performer. Farmers liked it because the cane had a higher agricultural yield (mt/ha; farmers are paid by cane weight). Millers liked it because it had a higher sucrose yield. It was also disease and drought resistant.

The multi-location field trials enabled the variety to cross UP borders and gave farmers across Northern India confidence the variety would work for them. Co-0238 is now the dominant cane variety in the region, accounting for more than 80% of planting.

Co-0238 has transformed the fortunes of the whole UP sugar sector. As a result, Uttar Pradesh has moved in the last decade from swinging between 4m – 8.5m tonnes of sugar per year to consistently making more than 12m tonnes, meaning all-India is now a surplus sugar producer and exporter.

India’s First Solution: Subsidise Sugar Exports

For the Indian government, this change has created a major problem.

The Indian sugar economy is heavily regulated. Sugar is listed as an ‘essential commodity’. This means:

- The government sets the minimum cane price mills must pay to farmers.

- It also fixes a minimum domestic sugar price.

- Mills are not allowed to own land.

- Mills must receive and pay for cane grown within their government-set command area.

- Mills need permission from the local government to start/stop operations each season.

In effect, the Government controls how the sugar sector works, so any problems created by these rules also need to be solved by the Government.

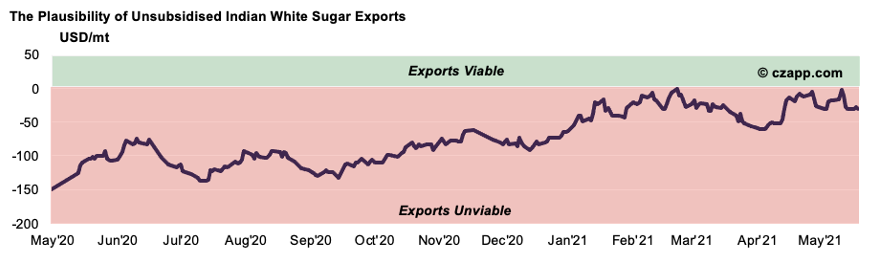

The fixed cane prices mean the cost of sugar production is high at around 30 INR/kg. Fixed domestic sugar prices at 31 INR/kg (425 USD/mt) means mills prefer to sell their sugar locally rather than export it.

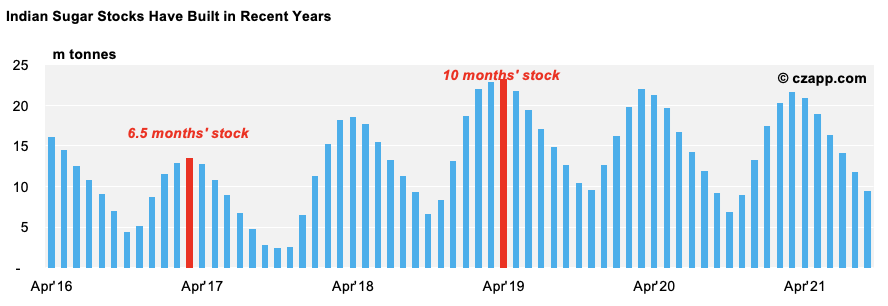

But India’s sugar overproduction means sugar stocks have built to alarmingly high levels, which is a logistical problem (mills need warehousing space) and a financial problem (mills need to insure and finance the stocks).

To solve this problem, the Indian government has offered mills sugar production/export subsidies since 2014 to encourage the surplus sugar to be shipped overseas; let it become someone else’s problem.

But India’s sugar exports have been a major reason the world market price of raw sugar has traded lower since 2017.

Source: Refinitiv Eikon

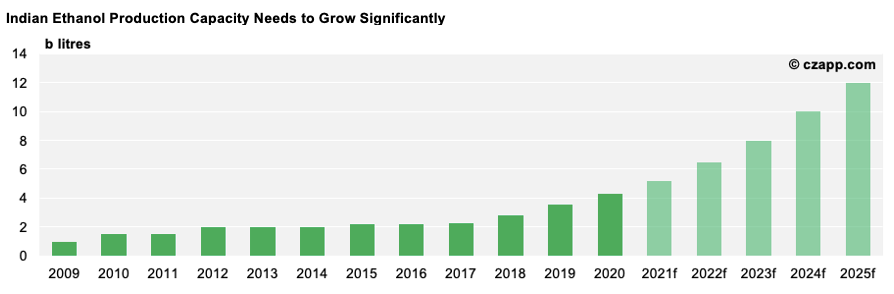

Other major sugar producers and exporters have seen their returns decline, and so together Australia, Brazil and Guatemala have launched a challenge at the World Trade Organisation (WTO) against India’s entire sugar economy with the aim of stopping India overproducing sugar and exporting the surplus.

A WTO decision could arrive in the next few months, but India firmly believes its subsidies are allowed under WTO rules, so is likely to challenge any adverse ruling. The dispute could easily drag on until 2022 and beyond.

However, India also admits that sugar export subsidies must finish by the end of 2023 under its interpretation of WTO rules, so it needs a new way to deal with surplus sugar, fast.

Which leads us onto its ethanol plans.

India’s Second Solution: Make Ethanol

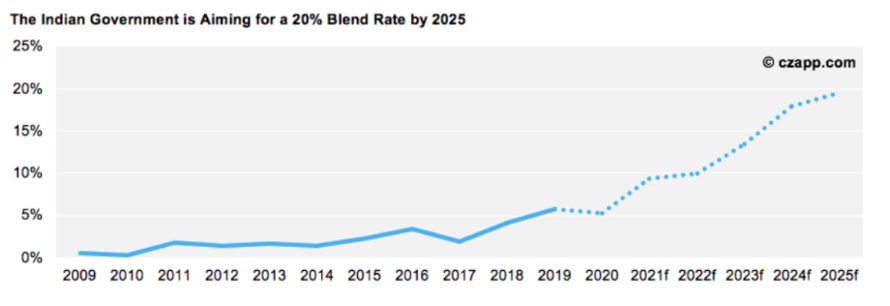

India’s government has set an ambitious goal. It wants to blend 20% ethanol into gasoline by 2025.

This is ambitious because:

1) In 2020, India’s ethanol blend was only around 5%. It’s going to be hard to quadruple this rate in five years.

2) Pre-COVID, Indian gasoline use was growing at around 7% a year; India’s gasoline demand doubles every decade.

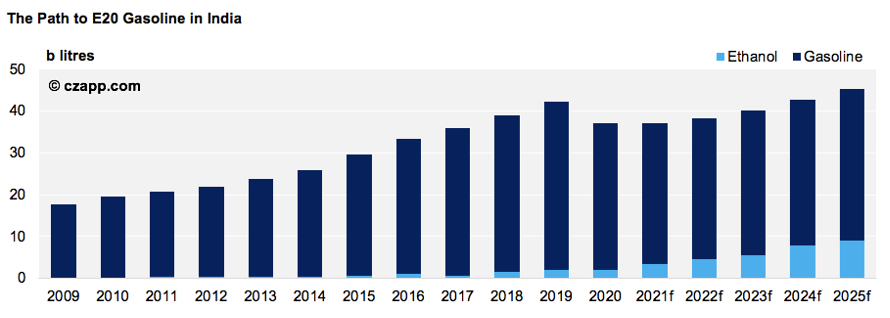

We think to reach a 20% blend by 2025, India will need to add 12b litres ethanol into gasoline. It currently makes around 4b litres.

The Government has offered a range of incentives to encourage sugar mills to invest in distillation to bridge the gap, most notably INR 165b low interest loans. Domestic ethanol prices have also been set at profitable levels for sugar mills.

Sugar cane uses carbon dioxide for photosynthesis while growing, so using cane-derived ethanol as a fuel can lead to lifecycle greenhouse gas emission reductions of 19-48%1 compared to using pure gasoline.

Indirectly, a group of Indian plant breeders have given birth to India’s ethanol blending programme, which might save millions of tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions each year. As well as supporting Indian farmers and sugar mills, they are accidental climate heroes.

1) Wang et al., (2012) Well-to-wheels energy use and greenhouse gas emissions of ethanol from corn, sugarcane and cellulosic biomass for US use. Environmental Research Letters 7 04 5905

Other Opinions You Might Be Interested In…

Explainers You Might Be Interested In…